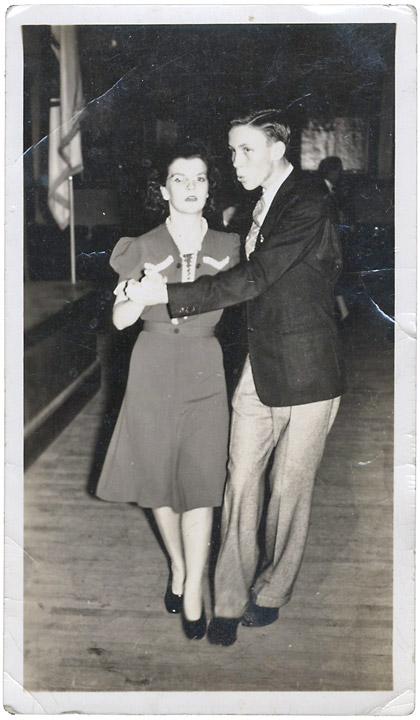

Sorry I’ve been absent here so long. My dad, who was in fragile health for a couple years, went through a sharp decline in early November. He died on Dec. 2. He was 88, lived a long full life, and died in his bed with my mom holding his hand. We have a lot to be grateful for, I know, but I miss him terribly each day. I had the task of writing his obituary and you can read it here. The ideal version, though, would have a pile of footnotes. Next to the description of him as “indefatigable,” for example, there’d be an asterisk offering this translation: “He wasn’t easy — but on the other hand, we were never bored.”

Sorry I’ve been absent here so long. My dad, who was in fragile health for a couple years, went through a sharp decline in early November. He died on Dec. 2. He was 88, lived a long full life, and died in his bed with my mom holding his hand. We have a lot to be grateful for, I know, but I miss him terribly each day. I had the task of writing his obituary and you can read it here. The ideal version, though, would have a pile of footnotes. Next to the description of him as “indefatigable,” for example, there’d be an asterisk offering this translation: “He wasn’t easy — but on the other hand, we were never bored.”

Here is a little more that’s not in the obituary: My dad was born to parents who were advanced in years and didn’t much want a child, let alone an “indefatigable” one. Then the Depression came and his father lost everything, including the will to go on. My dad spent most of his teens hanging out at the Marlborough firehouse because he didn’t feel welcome at home. I remember him telling me once that he was always hungry. In an attic somewhere there’s a copy of a letter he wrote at 16 to an area businessman asking for advice on how he could get on in the world. Then he joined the Navy and shipped off to the South Pacific. I write this to point out that my father understood hard times and loneliness, and the gifts he had — his scrappiness, his sense of humor, his generosity to others, his tolerance — seem bound up to me with the boy he was.

I remember once coming home from school, feeling bleak in that hopeless way that happens when you’re a kid and can’t even begin to express what’s going on to adults. I forget what the specific trouble was, but it must have been a time when I was “out” at school. That happened once in a while. My mom spoiled me but she didn’t understand; she was (and remains) the sort of person who’s largely impervious to the idea of fitting in (one of the first sayings she taught me was: “F**k ’em if they can’t take a joke”), which is a great quality but one I didn’t inherit. I remember my dad — who could be loud and impatient, who usually wanted me to come hold a lawn bag open for him while he raked up leaves or help him pick up dog crap in the backyard — sort of peering at me when I came in, and then later that afternoon he made me milk-on-toast in a bowl, something I had never had before, and we sat on the high stools in the kitchen looking out the window together, and I felt immeasurably comforted. I don’t remember talking to him about what was going on. I didn’t have to. He could be good company like that. He must have been 60 then; he’d recently retired against his own inclination (he had become “out” at work), and it was still strange to have him at home.

My stepson wrote my mom a beautiful letter after my dad’s death, and he’s given me permission to quote from it, “Dana to me was a presence of wry joyfulness. He had a rare talent for making fun of things without reducing their value. I always got the feeling that his humor was coming from a sincere and intimate place. He was an easy guy to be around — though I should take care not to oversimplify him because I know he could certainly stir things up when he felt like it. I never had to wonder with Dana whether I was getting the whole picture or not, and that always made me feel comfortable.” My stepdaughter’s card also made me cry. It said simply, “We’ll miss him too.”

We’re holding the memorial celebration this coming Sunday, on what would have been his 89th birthday. I’m looking forward to being with my mom, my three half-siblings, a handful of nieces and nephews, as well as an amazing number of the friends my dad made as he went through the world. Please think of us and raise a toast if you can.

Archives for January 2010

TT: One more once

My guess is that I’ve probably passed on enough Pops-related links, but here are two more that might interest you:

• The Huffington Post has posted a link to the podcast version of my hour-long interview with Christopher Lydon. This was the most satisfying audio-only interview that I’ve done about Pops to date, partly because it was so well produced but mostly because Lydon was so well prepared. In truth it’s a conversation, not an interview, and my only regret is that Lydon and I weren’t in the same studio (he was in Boston, I at NPR’s headquarters in Washington, D.C.). Go here to listen.

Warning, Mom: I say two words out loud in this interview that you won’t want to hear. Cover your ears and forgive me–I was only quoting Satchmo!

• The Los Angeles Public Library has posted a podcast of the version of my stump speech that I gave there last month. Go here to download it.

TT: Almanac

“Thought is only a gleam in the midst of a long night. But it is this gleam which is everything.”

Henri Poincaré, The Value of Science (trans. George B. Halsted)

TT: Entry from an unkept diary

• I’ve been sprinting on a treadmill since The Letter went into rehearsal last summer, and the unexpected success of Pops has turned the speed up several notches. I like what’s happening to me, but I don’t care for some of the side effects.

At the moment I have five jobs, all of them variously demanding: drama critic and arts journalist, biographer, opera librettist, itinerant book-flogger, and visiting scholar-in-residence. One unforeseen consequence of my near-ceaseless activity is that I’ve temporarily lost the power to relax. I wake up at six-thirty each morning as if prodded by a prison guard, and I find it difficult to sit and do nothing on the rare occasions when it’s possible for me to do so. I’m not listening to much music, either, though I can still read for pleasure, especially on trains. Only the other day I wolfed down FDR’s Deadly Secret like a fast-food burger on the Acela Express from Washington to New York. For the most part, though, I seem to be going directly from taxi to airport to hotel to lunch to interview to dinner to show to bed, then starting the cycle over again.

Conspicuously absent from this hectic sequence of events is contemplation. Though I now know for sure what my next biography will be and also have a pretty good idea of what my next opera libretto is likely to be, I haven’t had much time in recent weeks to stare into space and let my imagination play freely over these projects, much less to spin others out of the air. I actually found myself working on an airplane last night instead of gazing out the window and reveling in the view, which is what I usually do when flying.

Conspicuously absent from this hectic sequence of events is contemplation. Though I now know for sure what my next biography will be and also have a pretty good idea of what my next opera libretto is likely to be, I haven’t had much time in recent weeks to stare into space and let my imagination play freely over these projects, much less to spin others out of the air. I actually found myself working on an airplane last night instead of gazing out the window and reveling in the view, which is what I usually do when flying.

While the hubbub caused by Pops will die down fairly soon, I’m still going to be busy, and though I want to be busy, I’m not at all sure how busy I want to be. In a perfect world I’d settle for a single career, but one of the reasons why I do all the different things I do is that none of them pays me quite enough to stay afloat in New York City. Nor would I find it easy to give up any of them, for each is incredibly gratifying and stimulating in its own right.

In addition, I hasten to point out that I have other good reasons for doing all this work. Not only is it gratifying, but it’s also self-propagating: fresh opportunities to do exciting things next year are coming to me because of the exciting things I’m doing now. As a thug in The Long Goodbye explained to Philip Marlowe, “I got to make lots of dough to juice the guys I got to juice in order to make lots of dough to juice the guys I got to juice.” What has vanished along the way, at least for the moment, is the wasted time that is never wasted, the fallow idleness that eventually bears unforeseen fruit. Will my imagination dry up a year from now because I was too busy to daydream today? I wonder.

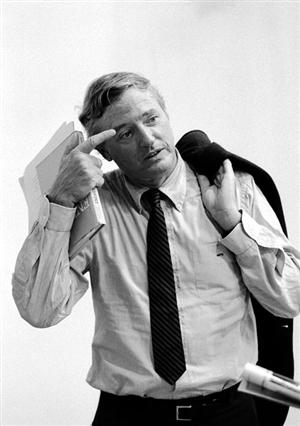

In 1971 Bill Buckley wrote a book called Cruising Speed in which he described a week in his own horrendously crowded life. At the end he pauses for a moment to consider a letter he had just received from “Herbert,” a historian who urged him to turn from his incessant public pursuits and spend more time in intellectual contemplation. “What will be your thoughts,” Herbert wrote, “if when you come to your deathbed you look back and realize that all your life amounted to no more than one big highly successful game of power and self-glorification?”

In 1971 Bill Buckley wrote a book called Cruising Speed in which he described a week in his own horrendously crowded life. At the end he pauses for a moment to consider a letter he had just received from “Herbert,” a historian who urged him to turn from his incessant public pursuits and spend more time in intellectual contemplation. “What will be your thoughts,” Herbert wrote, “if when you come to your deathbed you look back and realize that all your life amounted to no more than one big highly successful game of power and self-glorification?”

The letter brought Bill up short, and caused him to ask of himself the hard questions that can be found in the penultimate paragraph of Cruising Speed:

Herbert is hauntingly right–c’est que la vérité qui blesse–what are my reserves? How will I satisfy them, who listen to me today, tomorrow? Hell, how will I satisfy myself tomorrow, satisfying myself so imperfectly, which is not to say insufficiently, today; at cruising speed?

I have been no less haunted by that passage ever since I first read it years ago. It never occurred to me to ask Bill about it–I didn’t know him well enough–but I wondered when he died in 2008 whether he was still asking himself the same questions. I’m asking them of myself now, and so far I don’t have any answers, good or bad.

TT: Pat Metheny’s player piano

If you’re at all interested in Pat Metheny, or the mechanical reproduction of music, this seven-minute video about Orchestrion, his upcoming album from Nonesuch, will be the most interesting piece of film that you’re likely to see today:

Orchestrion goes on sale January 26.

TT: Almanac

“Curiously enough, one cannot read a book: one can only reread it. A good reader, a major reader, an active and creative reader is a rereader.”

Vladimir Nabokov, Lectures on Literature (courtesy of Anecdotal Evidence)

TT: Playwright in greasepaint

In today’s Wall Street Journal I review regional revivals of two of my favorite plays, Steppenwolf’s American Buffalo in Chicago and Jobsite Theater’s What the Butler Saw in Tampa. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

These days it’s no secret that the author of “Superior Donuts” and “August: Osage County” is a superior playwright, but Tracy Letts’ parallel career as a stage actor is mostly known only to those Chicagoans who see him performing on occasion with the Steppenwolf Theatre Company. I reviewed the 2005 Off-Broadway production of Austin Pendleton’s “Orson’s Shadow” in which Mr. Letts played Kenneth Tynan, so I know what he can do. Now he’s appearing in Steppenwolf’s revival of David Mamet’s “American Buffalo,” and his performance is one of the many highlights of a production so strong that I don’t see how it could be bettered.

Unlike “Race,” Mr. Mamet’s latest effort, which is good but not first-rate, “American Buffalo” is one of the best American plays of the past half-century, a harsh, hurtful portrait of three small-time Chicago crooks who can’t figure out how to make it in a money-hungry world that has no room for losers. This production, directed by Amy Morton, who graced the original cast of “August: Osage County,” is as blunt and unsparing as a fist in the kidney. It is also very, very funny–I’ve never seen an “American Buffalo” that got more laughs–which makes the explosion of violence that is the play’s climax still more shocking. Above all, Ms. Morton and her cast convey with exceptional clarity the extent to which “American Buffalo” is rooted in a specific time and place, Chicago in the mid-’70s….

“What the Butler Saw” is, after “Noises Off,” the most perfect farce to be written in modern times, a masterpiece of satirical savagery disguised as a lightweight sex comedy about extramarital hanky-panky in a lunatic asylum. Joe Orton wrote it in a state of controlled rage at the hypocrisies, sexual and otherwise, of the British establishment, and he made each punch line count. Not only are the jokes wickedly amusing in every sense of the adverb, but they’re embedded in a slam-door-A-then-run-through-door-B plot so tightly constructed that the play almost directs itself–so long as you trust the material. Alas, I’ve yet to see a staging of “What the Butler Saw” whose director was willing to let Orton be Orton, and Jobsite Theater’s revival, for all its noisy gusto, makes the usual mistake of overegging the comic pudding….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Here’s a scene from Steppenwolf’s production of American Buffalo:

TT: Almanac

“Society cannot share a common communication system so long as it is split into warring factions.”

Bertolt Brecht, A Short Organum for the Theatre (trans. John Willett)