Esa-Pekka Salonen conducts the Los Angeles Philharmonic in the “Death Hunt” cue from Bernard Herrmann’s score for Nicholas Ray’s On Dangerous Ground:

Go here to see the main titles from On Dangerous Ground.

(This is the latest in a weekly series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Wednesday.)

Archives for 2009

TT: Almanac

“Music arouses in us various emotions, but not the more terrible ones of horror, fear, rage, etc. It awakens rather the gentler feelings of tenderness and love, which readily passes into devotion.”

Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man

TT: On the air

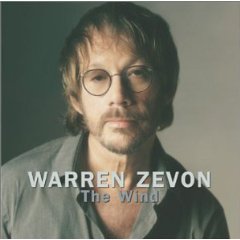

On Monday I appeared on Soundcheck, WNYC’s daily talk show about music, to talk about my Wall Street Journal column about deathbed masterpieces with John Schaefer, the host of Soundcheck. Also on the program was Crystal Zevon, the widow of Warren Zevon, who wrote and recorded his last album, The Wind, after he learned that he was dying of cancer.

On Monday I appeared on Soundcheck, WNYC’s daily talk show about music, to talk about my Wall Street Journal column about deathbed masterpieces with John Schaefer, the host of Soundcheck. Also on the program was Crystal Zevon, the widow of Warren Zevon, who wrote and recorded his last album, The Wind, after he learned that he was dying of cancer.

Alas, I wasn’t able to post a notice about my Soundcheck appearance due to circumstances beyond my control, but the episode has been archived, and you can listen to it via streaming audio on your computer by going here.

TT: Almanac

“I have (this sounds like fantastic nonsense, but it isn’t) frequently caught myself positively solving some problem (of a more or less philosophical nature) in, say, the key of A minor, where I had utterly failed to reason it out in words.”

Donald Francis Tovey (quoted in Mary Grierson, Donald Francis Tovey: A Biography Based on Letters)

OGIC: First paragraphs I love

It’s so easy to stop reading a book. To find a first paragraph that commands one’s extended attention at once is rare. Even among books I adore, few hit their first few hundred words out of the park. Almost all of them need a grace period of two or three or twenty pages to hook you. Here’s a paragraph that I think is a great beginning of a book:

Nolan pulls into the parking garage, braced for the Rican attendant with the cojones big enough to make a point of wondering what this rusted hunk of Chevy pickup junk is doing in Jag-u-ar City. But the ticket-spitting machine doesn’t much care what Nolan’s driving. It lifts its arm, like a benediction, like the hand of God dividing the Red Sea. Nolan passes a dozen empty spots and drives up to the top level, where he turns in beside a dusty van that hasn’t been anywhere lately. He grabs his duffel bag, jumps out, inhales, filling his lungs with damp cement-y air. So far, so good, he likes the garage. He wishes he could stay here. He finds the stairwell where he would hide were he planning a mugging, corkscrews down five flights of stairs, and plunges into the honking inferno of midafternoon Times Square.

That’s the first paragraph of Francine Prose’s novel A Changed Man, about a neo-Nazi trying to reform. It tells you a good deal about Nolan while dispensing gemlike phrases like “honking inferno.” And it left me wanting to know much more about the reluctance for which the character “passes a dozen empty spots and drives up to the top level.” It roped me right in. That doesn’t mean the book as a whole will deliver–though based on my previous experience reading Francine Prose, I expect it will, and then some.

I’ve become such an admirer of Prose this year, beginning January 1 when I bought her most recent novel, Goldengrove, on the basis of the title’s allusion to the Gerard Manley Hopkins poem and D. G. Myers’s recommendation. In the spring I read The Blue Angel, about a creative writing teacher entangled with a student. And last month I picked up one of her young adult novels, After, out of curiosity (retrieving the link above, I saw that Myers recently posted a review of a new YA novel by Prose). I’m more comforted than cowed to see that twelve further Prose novels await me after I finish A Changed Man. The ones I’ve read so far are real tours de force.

(If you get a chance to see Prose read or speak, take advantage of it. She was here in March to read a new story and take questions about Goldengrove, and it was a riveting evening even for someone who isn’t generally a fan of readings. She’s formidably smart and says what she thinks–she was most interesting talking about subjects I didn’t agree with her about.)

Previous books whose first paragraphs I love include Elaine Dundy’s The Old Man and Me, now widely available, wonderfully.

TT: Consumables

• What I saw on Broadway over the weekend: Keith Huff’s A Steady Rain (with Daniel Craig and Hugh Jackman) and Tracy Letts’ Superior Donuts, both of which open this week.

• What I’m listening to: Rosanne Cash’s The List (out October 6 from Manhattan) and Nellie McKay’s Normal as Blueberry Pie: A Tribute to Doris Day (out October 13 from Verve).

• What I’m listening to: Rosanne Cash’s The List (out October 6 from Manhattan) and Nellie McKay’s Normal as Blueberry Pie: A Tribute to Doris Day (out October 13 from Verve).

• What I’m reading: Farber on Film: The Complete Film Writings of Manny Farber (out on Thursday from the Library of America) and Simon Louvish’s Mae West: It Ain’t No Sin.

Watch this space for further details….

TT: Almanac

“Just as the liar’s punishment is, not in the least that he is not believed, but that he cannot believe any one else; so a guilty society can more easily be persuaded that any apparently innocent act is guilty than that any apparently guilty act is innocent.”

George Bernard Shaw, The Quintessence of Ibsenism

TT: A Cabaret to believe in

I wind up my summer travels this week with reviews of two out-of-town musicals, Trinity Rep’s Cabaret in Providence, Rhode Island, and Paper Mill Playhouse’s Little House on the Prairie in Millburn, New Jersey. The first is a gem, the second a dud. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

More people, I suspect, know “Cabaret” as a movie rather than a stage show nowadays. Bob Fosse’s hard-edged, bisexually frank 1972 screen version, in which Joe Masteroff’s book was completely rewritten and all but one of the songs were performed in a more or less naturalistic nightclub setting, was the most influential movie musical of the post-“Hair” era. Not only did Rob Marshall’s 2002 film of “Chicago” owe everything to Fosse’s example, but most of the major stage revivals of “Cabaret,” including Sam Mendes’ long-running 1999 Broadway production, have incorporated various elements inspired by or purloined from the Fosse film.

Curt Columbus, the artistic director of Rhode Island’s Trinity Repertory Company, has taken a different tack in his new revival of “Cabaret.” Instead of trying to put Fosse’s “Cabaret” on stage, he has given us a show that is substantially faithful to what Masteroff, John Kander and Fred Ebb had in mind in the first place. This “Cabaret,” unlike the film version, is an old-fashioned two-couple Broadway love story with a bracingly Brechtian dash of bitters: The songs sung by the bizarrely androgynous master of ceremonies of the Kit Kat Club (Joe Wilson, Jr.) supply ironic commentary on the futility of looking for love in a world driven mad by politics. The doomed romance of Fräulein Schneider (Phyllis Kay) and Herr Schultz (Stephen Berenson), her hapless Jewish boarder, is returned to center stage, while Sally Bowles (Rachael Warren) is not a top-dollar glamour puss but a middling hoofer who gets by on charm. Best of all, Mr. Columbus and Michael McGarty, his set designer, have hosed the polish off “Cabaret,” setting their production in a run-down Weimar-era music hall that could easily have housed a real-life Kit Kat Club….

Curt Columbus, the artistic director of Rhode Island’s Trinity Repertory Company, has taken a different tack in his new revival of “Cabaret.” Instead of trying to put Fosse’s “Cabaret” on stage, he has given us a show that is substantially faithful to what Masteroff, John Kander and Fred Ebb had in mind in the first place. This “Cabaret,” unlike the film version, is an old-fashioned two-couple Broadway love story with a bracingly Brechtian dash of bitters: The songs sung by the bizarrely androgynous master of ceremonies of the Kit Kat Club (Joe Wilson, Jr.) supply ironic commentary on the futility of looking for love in a world driven mad by politics. The doomed romance of Fräulein Schneider (Phyllis Kay) and Herr Schultz (Stephen Berenson), her hapless Jewish boarder, is returned to center stage, while Sally Bowles (Rachael Warren) is not a top-dollar glamour puss but a middling hoofer who gets by on charm. Best of all, Mr. Columbus and Michael McGarty, his set designer, have hosed the polish off “Cabaret,” setting their production in a run-down Weimar-era music hall that could easily have housed a real-life Kit Kat Club….

The strength of this strongly atmospheric production lies not in its individual performances but in its total effect. It is, above all, a believable “Cabaret,” one that has the sharp and satisfying bite of authenticity….

The “Little House” novels of Laura Ingalls Wilder rank high among the permanent masterpieces of childhood, in large part because of the plain-spoken authenticity with which Wilder told her richly detailed autobiographical stories of pioneer life. It would take an Adam Guettel–or an Aaron Copland–to conceive and create a worthy musical-theater counterpart to what Wilder did in prose. The creators of “Little House on the Prairie: The Musical,” which opened at Minneapolis’ Guthrie Theatre last year and is now touring the regional circuit, haven’t even tried. Instead, they’ve cuted up Wilder’s books into something more like “One-Room High School Musical.” The songs, by Rachel Portman and Donna di Novelli, are slick, innocuous movie-score pop, while Rachel Sheinkin’s book, which stitches together familiar pieces of “By the Shores of Silver Lake,” “The Long Winter” and “Little Town on the Prairie,” is clumsily episodic and devoid of dramatic impetus….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.