“The people are a sovereign whose vocabulary is limited to two words, ‘Yes’ and ‘No.’ This sovereign, moreover, can speak only when spoken to.”

E.E. Schattenschneider, Party Government: American Government in Action

Archives for November 2009

TT: Sometimes Macy’s does tell Gimbel’s!

Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong got a rave from Michiko Kakutani of the New York Times:

With “Pops,” his eloquent and important new biography of Armstrong, the critic and cultural historian Terry Teachout restores this jazzman to his deserved place in the pantheon of American artists, building upon Gary Giddins’s excellent 1988 study, “Satchmo: The Genius of Louis Armstrong,” and offering a stern rebuttal of James Lincoln Collier’s patronizing 1983 book, “Louis Armstrong: An American Genius.”

Mr. Teachout…writes with a deep appreciation of Armstrong’s artistic achievements, while situating his work and his life in a larger historical context. He draws on Armstrong’s wonderfully vivid writings and hours of tapes in which the musician recorded his thoughts and conversations with friends, and in doing so, creates an emotionally detailed portrait of Satchmo as a quick, funny, generous, observant and sometimes surprisingly acerbic man: a charismatic musician, who like a Method actor, channeled his vast life experience into his work, displaying a stunning, almost Shakespearean range that encompassed the jubilant and the melancholy, the playful and the sorrowful.

At the same time, Mr. Teachout reminds us of Armstrong’s gifts: “the combination of hurtling momentum and expansive lyricism that propelled his playing and singing alike,” his revolutionary sense of rhythm, his “dazzling virtuosity and sensational brilliance of tone,” in another trumpeter’s words, which left listeners feeling as though they’d been staring into the sun. The author–who worked as a jazz bassist before becoming a full-time writer–also uses his firsthand knowledge of music to convey the magic of such Armstrong masterworks as “St. Louis Blues,” “Potato Head Blues,” “West End Blues” and “Star Dust.”…

I think this must be the first time that anyone has ever called me a “cultural historian” in print.

Read the whole thing here.

TT: A sight to see

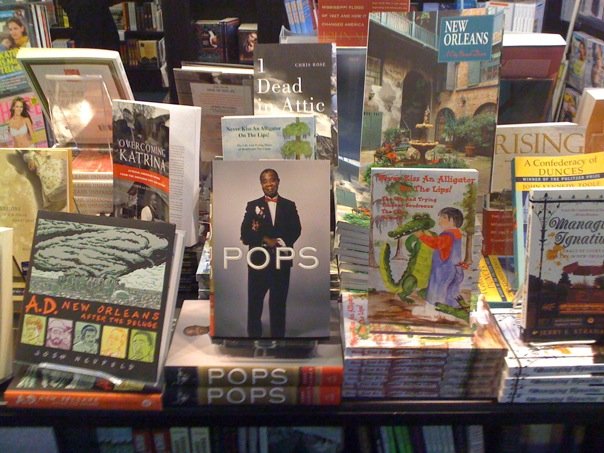

My friend Laura Lippman sent me this snapshot of Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong on display at a bookstore in New Orleans’ Louis Armstrong International Airport.

My friend Laura Lippman sent me this snapshot of Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong on display at a bookstore in New Orleans’ Louis Armstrong International Airport.

Another friend in Washington, D.C., sends along this report:

You’ll be pleased to know that Pops is being showcased in the front window display of Politics and Prose, along with Ted Kennedy’s autobiography, Jonathan Safran Foer’s latest, and some other books.

You meet the most interesting people in a bookstore window….

TT: Vote for me!

The dust jacket of the American edition of Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong, designed by Mark Robinson, is one of the six nominees in the “Best Famous Faces” category of Amazon’s Best Cover of the Year competition.

If you like the cover of Pops as much as I do, vote for it by going here.

TT: The receiving end

As if putting up with one set of reviews in a single year hadn’t been enough, I’m now in the process of finding out what my colleagues think of Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong. So far the news has been highly gratifying, and over the weekend I scored another pair of raves.

As if putting up with one set of reviews in a single year hadn’t been enough, I’m now in the process of finding out what my colleagues think of Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong. So far the news has been highly gratifying, and over the weekend I scored another pair of raves.

The English edition of Pops is already out, and Robert Sandall called it “terrific” in the Sunday Times of London:

Teachout is especially good at exposing the difficulties that Armstrong experienced with critics and fellow musicians after he became famous. On his first tour of Britain in 1932 he was on one hand hailed as an innovator–“as modern as James Joyce”–and on the other dismissed as a circus act. The Daily Express man complained that “he looks and behaves like an untrained gorilla”. Another commentator mocked his “clean-shaven hippopotamus physiognomy.”

As time went by, opinion became even more polarised. Philip Larkin lauded him as “more important than Picasso”; Le Corbusier called him “equilibrium on a tightrope”. Meanwhile, a growing chorus of reviewers objected to the film roles, hit records and funny-guy stage patter. “Now he is a one-man show: comedian, jivester, and lastly musician,” was a widely voiced put-down. These jibes hurt. Armstrong was a far more shaded character than his sunny public persona let on. Teachout’s access to a previously unavailable archive of taped conversations and writings has allowed him to construct the most complete picture yet of a well-studied subject. In particular he captures Armstrong’s deep ambivalence to his predicament as a black celebrity in an industry run by whites….

Read the whole thing here.

Meanwhile, Ted Gioia, a much-admired jazz critic and historian who is also a professional jazz pianist, reviewed the American edition of Pops in the new issue of the Weekly Standard. The complete text of his review is only available to subscribers, but here are some pertinent excerpts:

Finally–almost four decades after Armstrong’s death in the summer of 1971–we have a biography that does justice to the man and his music….

Teachout is an astute critic who knows jazz deeply–and has even played it as a bassist–but is largely immune to the increasingly inward-focused attitudes that hinder the effectiveness of so many contemporary critics. He has previous biographies of H. L. Mencken and George Balanchine to his credit, and has written strong, supple criticism of dance, theater, and cinema. In short, Teachout seems perfectly suited to tackle this seminal figure whose career rarely stayed within the usual boundaries of jazz.

Teachout captures this broader context with great skill. His rich cast of characters includes not only musicians and record industry figures, but criminals and monarchs, TV personalities and movie stars. We follow Armstrong at a 1932 performance with King George V in attendance, tossing off the intro “This one’s for you, Rex”–then playing (unthinkingly?) “I’ll Be Glad When You’re Dead, You Rascal, You!” Elsewhere, we get a detailed look–the best I have read anywhere–of Armstrong’s dealings with the Mob. This artist first made his reputation in Al Capone’s Chicago, and even at the end of his life, his financial situation was affected by underworld influences. At other points we encounter Sammy Davis Jr., Johnny Cash, Leonard Bernstein, Bing Crosby, and Pope Pius XII, among other names worth dropping. My favorite anecdote tells of Herbert von Karajan berating the Vienna Philharmonic because its players can’t maintain a tempo as well as Armstrong’s band.

Teachout delivers a taut and well-paced work that is astute in its critical judgments and gripping in its chronicle of the trumpeter’s life and times….

I warned Mrs. T (who is new at this game) that the other shoe is bound to drop sooner or later, but so far, so good.

I’ve also been keeping an eye on the reader reviews of Pops posted on Amazon. Twenty-three had appeared as of this morning, all but one of them favorable. Some are smart, others less so, while a couple are decidedly, even amusingly off the wall. My guess, though, is that the average customer rating posted on Amazon’s Pops page is more important to potential buyers than any individual review, and as of this morning it stands at four-and-a-half stars out of a possible five.

As for print-media reviews, everybody in the business is wondering how much they matter these days. Probably not as much as they used to, and very possibly not much at all, though nobody knows for sure. All I can tell you is that good ones don’t hurt, and they’re a hell of a lot more fun to read than bad ones.

TT: Almanac

“I nodded and went out. There are days like that. Everybody you meet is a dope. You begin to look at yourself in the glass and wonder.”

Raymond Chandler, The Little Sister (courtesy of Mrs. T)

TT: Home, at last

This has been a wonderful week for New York-area theater, so busy that it took two columns in The Wall Street Journal for me to get it all in. Today I review two openings, the New York premieres of the first installment of Horton Foote’s The Orphans’ Home Cycle and Sarah Ruhl’s In the Next Room or the vibrator play. The first is a masterpiece, the second a piece of…well, something else altogether. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Horton Foote, who died in March at the age of 92, had to wait until the very end of his life to win general recognition as one of America’s greatest playwrights. The tide was turned by a sterling pair of Off-Broadway revivals, the Signature Theatre Company’s 2005 production of “The Trip to Bountiful” and Primary Stages’ 2007 production of “Dividing the Estate,” that opened the eyes of a new generation of theatergoers to Foote’s low-keyed mastery. When “Dividing the Estate” transferred to Broadway the following year, he scored his first commercial success on the New York stage–just in time for him to revel in it. Would that Foote could have lived to attend the New York opening of the first part of “The Orphans’ Home Cycle,” co-produced by Signature and Connecticut’s Hartford Stage, where all three installments were seen earlier this year. It will, I suspect, be remembered as the most significant theatrical event of the season, the kind of show you tell your grandchildren that you saw.

Created by Foote at the suggestion of Michael Wilson, the artistic director of Hartford Stage and the director of this production, “The Orphans’ Home Cycle” is a triptych carved out of a cycle of nine plays originally written between 1974 and 1997. It’s the story of a quarter-century in the life of a Texas family, and the family is Foote’s own, a flock of displaced people who are uprooted, scattered and damaged by the coming of modernity. The title alludes to Marianne Moore’s poem “In Distrust of Merits”: The world’s an orphans’ home. Shall/we never have peace without sorrow? At the center of the saga is Horace Robedaux, a fictionalized version of Foote’s real-life father (beautifully played as a child by Dylan Riley Snyder, as a teenager by Henry Hodges and as an adult by Bill Heck). Cast adrift by the death of his own alcoholic father and the remarriage of his mother to a resentful man who loathes his stepson, Horace becomes a stranger in a familiar land, searching for a peace that continually eludes him….

Created by Foote at the suggestion of Michael Wilson, the artistic director of Hartford Stage and the director of this production, “The Orphans’ Home Cycle” is a triptych carved out of a cycle of nine plays originally written between 1974 and 1997. It’s the story of a quarter-century in the life of a Texas family, and the family is Foote’s own, a flock of displaced people who are uprooted, scattered and damaged by the coming of modernity. The title alludes to Marianne Moore’s poem “In Distrust of Merits”: The world’s an orphans’ home. Shall/we never have peace without sorrow? At the center of the saga is Horace Robedaux, a fictionalized version of Foote’s real-life father (beautifully played as a child by Dylan Riley Snyder, as a teenager by Henry Hodges and as an adult by Bill Heck). Cast adrift by the death of his own alcoholic father and the remarriage of his mother to a resentful man who loathes his stepson, Horace becomes a stranger in a familiar land, searching for a peace that continually eludes him….

Not having seen the second or third parts, I can’t yet evaluate the total effect of the cycle as a whole, but “The Story of a Childhood” has the narrative sweep that you look for in major novels, coupled with the electric immediacy that only live theater can supply….

Sarah Ruhl writes retchingly coy plays that pretend to be transgressive–a sure-fire recipe for success of a sort. “In the Next Room or the vibrator play” (trendy capitalization and punctuation by Ms. Ruhl, not me) is an all-too-typical example of her method. It’s a fictionalized history play about a 19th-century American physician (Michael Cerveris) who discovers that “hysterical” women experience miraculous recoveries when he induces “paroxysms” by stimulating their nether regions with his brand-new invention, an electric vibrator….

“In the Next Room” is a sentimental wallow studded with sniggering jokes that too often appear to be made at the expense of Ms. Ruhl’s innocent characters, none of whom is believably Victorian in speech or carriage. The result is the theatrical equivalent of a jelly donut with vinegar-flavored frosting…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Almanac

“Rock journalism is people who can’t write interviewing people who can’t talk for people who can’t read.”

Frank Zappa (quoted in the Chicago Tribune, Jan. 18, 1978)