CAAF recently posted about a law-clerk friend who enjoys reading Chief Justice Roberts’ opinions because they’re so stylishly written. The same friend also cited a dissent by a circuit judge that starts out as follows:

It is said that the wife of English lexicographer Samuel Johnson returned home unexpectedly in the middle of the day, to find Dr. Johnson in the kitchen with the chambermaid. She exclaimed, “My dear Dr. Johnson, I am surprised.” To which he reputedly replied, “No my dear, you are amazed. We are surprised.”

To which a friend of mine replied:

He references Samuel Johnson. He has it wrong. It was Noah Webster, the great American lexicographer, who was with the chambermaid when the wife came in, and it was most likely apocryphal.

Irritation springs from two things. 1. You ain’t were gonna ever find old Samuel Johnson groping anyone, rumors of his relationship with Mrs. Thrale notwithstanding. He was famously a man of discipline, inhibition, awkwardness, and High Church guilt. 2. More and more I find people putting famous phrases in the mouths of the wrong people, e.g., “As Henry Luce said, ‘Accuracy to a newspaper is what virtue is to a woman…'” I would like everyone to stop this. Thank you.

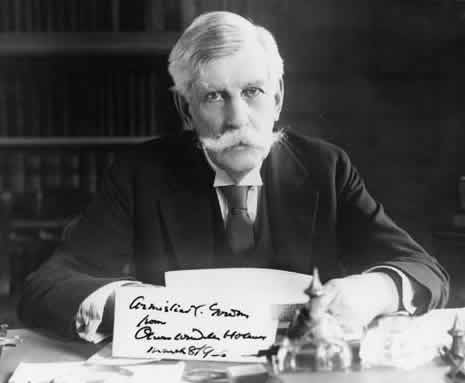

My own response to CAAF’s post was to think of Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., the only American jurist whose opinions are by way of being great literature, a fact that had much to do with their impact on non-lawyers throughout the twentieth century. Edmund Wilson, for one, observed in Patriotic Gore that Justice Holmes’ opinions were “so elegantly and clearly presented, so free from the cumbersome formulas and the obsolete jargon of jurists, that, though only an expert can judge them, they may profitably be read by the layman.”

My own response to CAAF’s post was to think of Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., the only American jurist whose opinions are by way of being great literature, a fact that had much to do with their impact on non-lawyers throughout the twentieth century. Edmund Wilson, for one, observed in Patriotic Gore that Justice Holmes’ opinions were “so elegantly and clearly presented, so free from the cumbersome formulas and the obsolete jargon of jurists, that, though only an expert can judge them, they may profitably be read by the layman.”

There, alas, is the rub. I’ve found that experts are less inclined to admire Justice Holmes than laymen, not because he wrote too prettily but because the beauty of his style sometimes lent undeserved force to deeply problematic views. Richard Posner, who edited a superb anthology of Holmes’ writings, put his finger on that tendency in his introduction to The Essential Holmes.

That Judge Posner admires Holmes’ style is not in doubt:

His majority and dissenting opinions alike are remarkable not only for the poet’s gift of metaphor that is their principal stylistic distinction, but also for their brevity, freshness, and freedom from legal jargon; a directness bordering on the colloquial; a lightness of touch foreign to the legal temperament; and an insistence on being concrete rather than legalistic–on identifying values and policies rather than intoning formulas. The content is sometimes formalistic, the form invariably realistic, practical.

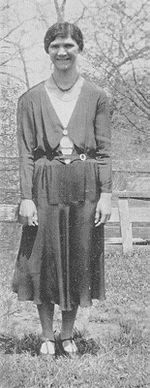

But he goes on to observe that “some of Holmes’ best opinions…owe their distinction to their rhetorical skill rather than to the qualities of their reasoning; often they are not well reasoned at all. In part at least, Holmes was a great judge because he was a great literary artist.” And Judge Posner, for all his understandable admiration of Justice Holmes, is no less quick to point to Buck v. Bell, the 1927 ruling in which the Supreme Court declared that it was constitutional for the state of Virginia to sterilize Carrie Buck, a retarded eighteen-year-old woman who had given birth to a retarded illegitimate child and whose own mother was also said to be retarded.

Justice Holmes wrote for the majority:

We have seen more than once that the public welfare may call upon the best citizens for their lives. It would be strange if it could not call upon those who already sap the strength of the State for these lesser sacrifices, often not felt to be such by those concerned, in order to prevent our being swamped with incompetence. It is better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind. The principle that sustains compulsory vaccination is broad enough to cover cutting the Fallopian tubes. Jacobson v. Massachusetts, 197 U.S. 11. Three generations of imbeciles are enough.

That is, as Judge Posner rightly observes, an aesthetically exquisite piece of rhetoric, but one whose implications are abhorrent, especially when read in light of the fact that some modern scholars now believe that Buck, who lived until 1983, may not in fact have been retarded at all.

I always remember the fate of Carrie Buck whenever I hear a judge praised for the literary artfulness of his opinions. I yield to no one in my admiration for what Walter Lippmann called “the grand style” of Justice Holmes’ writings. His was a great personality, one fully worthy of having been enshrined in the pages of Patriotic Gore, and it shines through every opinion that he wrote. But I squirm at the thought that the pith and vigor of his style may have increased the willingness of his fellow justices to order the eugenic sterilization of a teenage girl on wholly specious grounds.

I always remember the fate of Carrie Buck whenever I hear a judge praised for the literary artfulness of his opinions. I yield to no one in my admiration for what Walter Lippmann called “the grand style” of Justice Holmes’ writings. His was a great personality, one fully worthy of having been enshrined in the pages of Patriotic Gore, and it shines through every opinion that he wrote. But I squirm at the thought that the pith and vigor of his style may have increased the willingness of his fellow justices to order the eugenic sterilization of a teenage girl on wholly specious grounds.

Clement Greenberg said it: “There are, of course, more important things than art: life itself, what actually happens to you….Art solves nothing, either for the artist himself or for those who receive his art.” Perhaps the world would be a better place if more judges wrote well–but somehow I doubt it.