Joanna Pinsker, my publicist at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, recently asked me to prepare a “self-interview” about Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong that could be sent to radio and TV producers. I was more than happy to oblige. I’ve posted a link to the questions and answers in the right-hand column, but in case you didn’t notice it, you can read what I wrote by going here.

Assiduous readers of this blog won’t find any of the information surprising, but it might possibly interest you to see how modern-day authors go about publicizing their books.

Archives for September 2009

TT: Almanac

“The stupid believe that to be truthful is easy; only the artist, the great artist, knows how difficult it is.”

Willa Cather, The Song of the Lark

TT: You have the right to home delivery

How come nobody told me about these?

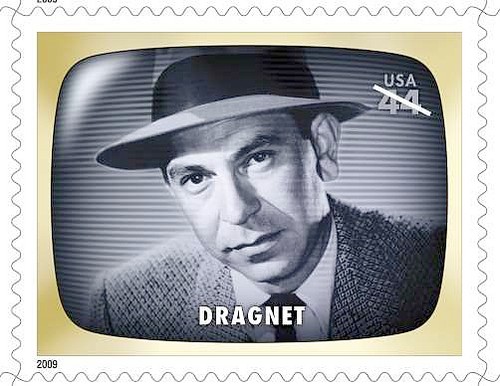

If you’ve never seen any of the original black-and-white Dragnet episodes from the Fifties–most of which, alas, have been out of circulation for decades–you don’t know what the show was really like. As I wrote in an essay called “In Praise of Drabness” that was published last year in National Review:

Like the later color version, the Dragnet of the Fifties was a no-nonsense half-hour police procedural that sought to show how ordinary cops catch ordinary crooks. The scripts, many of which were written by James E. Moser, combined straightforwardly linear plotting (“It was Wednesday, October 6. It was sultry in Los Angeles. We were working the day watch out of homicide”) with clipped dialogue spoken in a near-monotone, all accompanied by the taut, dissonant music of Walter Schumann. Then and later, most of the shots were screen-filling talking-head closeups, a plain-Jane style of cinematography that to this day is identified with Jack Webb.

The difference was that in the Fifties, Joe Friday and Frank Smith, his chubby, mildly eccentric partner, stalked their prey in a monochromatically drab Los Angeles that seemed to consist only of shabby storefronts and bleak-looking rooms in dollar-a-night hotels. Nobody was pretty in Dragnet, and almost nobody was happy. The atmosphere was that of film noir minus the kinks–the same stark visual grammar, only cleansed of the sour tang of corruption in high places. But even without the Chandleresque pessimism that gave film noir its seedy savor, Dragnet was still rough stuff, more uncompromising than anything that had hitherto been seen on TV. In 1954 Time called the series “a sort of peephole into a grim new world. The bums, priests, con men, whining housewives, burglars, waitresses, children, and bewildered ordinary citizens who people Dragnet seem as sorrowfully genuine as old pistols in a hockshop window.”

Here’s the opening sequence of “The Big Cast,” a 1952 Dragnet featuring Lee Marvin. It’ll give you a feel for what you’ve been missing:

TT: Almanac

My engines, after ninety days o’ race an’ rack an’ strain

Through all the seas of all Thy world, slam-bangin’ home again.

Rudyard Kipling, “M’Andrew’s Hymn”

FACING THE FINAL CURTAIN

“Why are deathbed masterpieces so unusual? Mainly, I suspect, because prettified Hollywood-style deaths, in which the sudden disappearance of makeup is the only outward sign that a terminal illness has reached its denouement, are so uncommon…”

TT: Some are more equal than others

I’m still on the road, and in today’s Wall Street Journal I report on the Repertory Theatre of St. Louis’ revival of Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus and the Lyric Stage Company of Boston’s production of Kiss Me, Kate. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Peter Shaffer rang the box-office gong twice in a row with “Equus” and “Amadeus,” both of which ran for well over a thousand performances on Broadway and have since been revived there, neither for very long. Yet they’re still spectacularly effective, and “Amadeus” is something more than that: Mr. Shaffer’s fictionalized portrayal of the musical rivalry between Antonio Salieri and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart is a powerful parable of the terrible mystery of human inequality. Alas, “Amadeus” is rarely seen on stage these days, partly because Milos Forman’s 1984 film version was so successful and partly because the play calls for a large and expensive cast. That’s what lured me to the Repertory Theatre of St. Louis’ new revival, a polished production authoritatively staged by Paul Mason Barnes that makes the strongest possible case for what in retrospect now looks like one of the best plays of the ’70s….

Nowadays, of course, most people know “Amadeus” from Mr. Forman’s film, an opulently designed costume piece that is great fun to watch but lacks the expressionistic intensity of the original play. In the stage version, by contrast, the spotlight never moves away from Salieri, an ambitious but modestly talented composer who is driven to the brink of madness by the inexplicable fact that supreme genius and juvenile vulgarity exist side by side in Mozart, his hated competitor: “It seemed to me that I had heard the voice of God–and that it issued from a creature whose own voice I had also heard–and that it was the voice of an obscene child!”

Nowadays, of course, most people know “Amadeus” from Mr. Forman’s film, an opulently designed costume piece that is great fun to watch but lacks the expressionistic intensity of the original play. In the stage version, by contrast, the spotlight never moves away from Salieri, an ambitious but modestly talented composer who is driven to the brink of madness by the inexplicable fact that supreme genius and juvenile vulgarity exist side by side in Mozart, his hated competitor: “It seemed to me that I had heard the voice of God–and that it issued from a creature whose own voice I had also heard–and that it was the voice of an obscene child!”

To impersonate so tortured a soul is a daunting task, but Andrew Long, who was terrific as Antony in the Shakespeare Theatre Company production of “Antony and Cleopatra” that I saw in Washington last summer, is up to the job. He plays Salieri as a grotesque, grim-faced clown, an interpretation very much in accord with Mr. Barnes’ staging, which emphasizes the comic aspect of “Amadeus” without lapsing into gross caricature….

If there’s a better musical than “Kiss Me, Kate,” I haven’t seen it. Yet Cole Porter’s masterpiece, near-perfect though it is, doesn’t get done nearly often enough, and I’ve no idea why. All the more reason, then, to welcome the Lyric Stage Company of Boston’s engaging new production, directed by Spiro Veloudos, whose small scale does nothing to diminish the charms of Porter’s updated version of “The Taming of the Shrew.”

To cram a classic Broadway musical into a 200-seat house requires considerable ingenuity, and I was especially impressed by the choreography of Ilyse Robbins, whose production numbers, especially “Too Darn Hot” and “Always True to You in My Fashion” (the second of which shows off the excellent dancing of Michele A. DeLuca to sumptuous effect), are all the more exciting for being performed in the lap of the audience….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Last time’s a charm

Erich Kunzel, the conductor of the Cincinnati Pops Orchestra, conducted his last concert on August 1, exactly a month before he died. This event put me in mind of the surprisingly small number of performances that have been given and masterpieces that have been created by artists who knew they were dying, and–not so surprisingly–a “Sightings” column came out of my reflections on this grim subject.

Erich Kunzel, the conductor of the Cincinnati Pops Orchestra, conducted his last concert on August 1, exactly a month before he died. This event put me in mind of the surprisingly small number of performances that have been given and masterpieces that have been created by artists who knew they were dying, and–not so surprisingly–a “Sightings” column came out of my reflections on this grim subject.

Why are deathbed masterpieces like Edouard Manet’s “Vase of White Lilacs and Roses” so rare, and what do they tell us about the dark encounter that awaits us all? Pick up a copy of Saturday’s Wall Street Journal to see what I have to say.

UPDATE: Read the whole thing here.

* * *

Edward G. Robinson’s death scene in Soylent Green was filmed just twelve days before he died. You can view it by going here.

TT: Almanac

“We are going to die, and that makes us the lucky ones. Most people are never going to die because they are never going to be born. The potential people who could have been here in my place but who will in fact never see the light of day outnumber the sand grains of Sahara. Certainly those unborn ghosts include greater poets than Keats, scientists greater than Newton. We know this because the set of possible people allowed by our DNA so massively outnumbers the set of actual people. In the teeth of these stupefying odds it is you and I, in our ordinariness, that are here.”

Richard Dawkins, Unweaving the Rainbow: Science, Delusion and the Appetite for Wonder