I’m still on the road in New England, where I reviewed the Peterborough Players’ Heartbreak House in New Hampshire and the Berkshire Theatre Festival’s Ghosts in Stockbridge. Both productions are excellent, but only one of these two classic plays of Vicwardian manners remains viable today. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

You can tell any truth, however hurtful, so long as you say it with a smile. That was the secret of George Bernard Shaw’s success, and “Heartbreak House” shows his method at its most theatrically effective. Rarely have England’s chattering classes been sketched so savagely, but Shaw tells his brutal truths with such impish charm that you scarcely feel the knife slipping in until the blood starts to flow. Therein lies the strength of the Peterborough Players’ production of “Heartbreak House,” which Gus Kaikkonen has staged with the lightest possible touch. It plays like a Noël Coward-style comedy of bad manners–until the climactic moment when the ground opens up beneath the feet of the characters.

Written between 1913 and 1919 and set in the first days of World War I, “Heartbreak House” takes place in the country home of Captain Shotover (George Morfogen), a retired sailor of great age who has the alarming habit of popping into a room, saying whatever happens to be on his mind, then popping out again. The captain and his family seem at first glance to be charming to a fault, a veritable fountain of epigrammatic cleverness. One of their guests describes them as “unprejudiced, frank, humane, unconventional, democratic, free-thinking, and everything that is delightful to thoughtful people.” Yet mere minutes after these words are spoken, the Shotovers find themselves in the midst of a German aerial bombardment, and they rejoice in the devastation that threatens to consume them and the rest of their delightful kind….

Every member of Mr. Kaikkonen’s ensemble cast gives a sharply and memorably drawn performance, starting with Mr. Morfogen, whose Captain Shotover is a fey, shambling sprite…

As a critic, Shaw championed the plays of Henrik Ibsen, and as a playwright he learned from Ibsen’s willingness to skewer the hypocrisies of the 19th-century middle class about which he wrote. Yet Shaw was the better artist, and I don’t doubt that he knew it. In “The Quintessence of Ibsenism,” his 1891 tribute to the man who cleared the way for his own plays of ideas, Shaw described Ibsen’s “Ghosts” as “such an uncompromising and outspoken attack on marriage as a useless sacrifice to an ideal, that his meaning was obscured by its very obviousness.” I thought of those backhanded words of praise as I watched the Berkshire Theatre Festival’s imaginative revival of “Ghosts.” In 1881 “Ghosts” swept across the stage like a tornado of frankness, but today it comes across as a preachy piece of bourgeois-baiting…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Archives for August 2009

TT: The new-media crisis of 1949

The more things change, the more they stay the same. The coming of television killed off network radio in a way that’s startlingly reminiscent of the effect that the digital revolution is currently having on network TV, the print media, and the music business.

The more things change, the more they stay the same. The coming of television killed off network radio in a way that’s startlingly reminiscent of the effect that the digital revolution is currently having on network TV, the print media, and the music business.

Are there any useful lessons to be learned from what happened to old-time network radio in the quarter-century that preceded its final demise in 1962? I think so, and I’ve tried to sum them up in my latest “Sightings” column for tomorrow’s Wall Street Journal. Here’s an excerpt:

Americans of all ages embraced TV unhesitatingly. They felt no loyalty to network radio, the medium that had entertained and informed them for a quarter-century. When something came along that they deemed superior, they switched off their radios without a second thought. That’s the biggest lesson taught by the new-media crisis of 1949. Nostalgia, like guilt, is a rope that wears thin….

Can the old media shore up their questionable future by looking to the not-quite-so-distant past? To find out, pick up a copy of Saturday’s Journal and see what I have to say.

UPDATE: Read the whole thing here.

TT: Almanac

“It’s very hard to be a gentleman and a writer.”

W. Somerset Maugham, Cakes and Ale

TT: So you want to see a show?

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

Warning: Broadway shows marked with an asterisk were sold out, or nearly so, last week.

BROADWAY:

• Alfred Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps (comedy, G, suitable for bright children, reviewed here)

• South Pacific * (musical, G/PG-13, some sexual content, brilliantly staged but unsuitable for viewers acutely allergic to preachiness, reviewed here)

OFF BROADWAY:

• The Fantasticks (musical, G, suitable for children capable of enjoying a love story, reviewed here)

• Our Town (drama, G, suitable for mature children, reviewed here)

IN ASHLAND, OREGON:

• The Music Man (musical, G, very child-friendly, closes Nov. 1, reviewed here)

IN CHICAGO:

• The History Boys (drama, PG-13/R, adult subject matter, too intellectually complex for most adolescents, closes Sept. 27, reviewed here)

IN EAST HADDAM, CONN.:

• Camelot (musical, G, closes Sept. 19, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON ON BROADWAY

• Avenue Q * (musical, R, adult subject matter and one show-stopping scene of puppet-on-puppet sex, closes Sept. 13, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON OFF BROADWAY

• Ruined (drama, PG-13/R, sexual content and suggestions of extreme violence, closes Sept. 6, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON IN GARRISON, N.Y.:

• Pericles and Much Ado About Nothing (Shakespeare, PG-13, playing in repertory through Sept. 6, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON IN LENOX, MASS:

• Twelfth Night (Shakespeare, PG-13, closes Sept. 5, reviewed here)

CLOSING NEXT WEEK ON BROADWAY:

• The Little Mermaid * (musical, G, entirely suitable for children, closes Aug. 30, reviewed here)

CLOSING NEXT WEEK IN PITTSFIELD, MASS:

• A Streetcar Named Desire (drama, PG-13/R, closes Aug. 29, reviewed here)

TT: Almanac

“It is cruel to discover one’s mediocrity only when it is too late.”

W. Somerset Maugham, Of Human Bondage

TT: Two little words

I’ve been too busy to say anything about the outpouring of responses to my Wall Street Journal column about the shrinking audience for jazz in America. Much of what’s been written about “Can Jazz Be Saved?” (though not all) has been angry, and most of it misses the point.

The latest writer to sound off is Nate Chinen, who responded in the New York Times with a piece called “Doomsayers May Be Playing Taps, but Jazz Isn’t Ready to Sing the Blues.” Chinen’s piece, though it lacks the hysterical edge of some of the recent blog postings about my column, sticks fairly closely to what has become the standard line about “Can Jazz Be Saved?” It revolves around two little words:

The latest writer to sound off is Nate Chinen, who responded in the New York Times with a piece called “Doomsayers May Be Playing Taps, but Jazz Isn’t Ready to Sing the Blues.” Chinen’s piece, though it lacks the hysterical edge of some of the recent blog postings about my column, sticks fairly closely to what has become the standard line about “Can Jazz Be Saved?” It revolves around two little words:

Mr. Teachout wasn’t the first to sound an alarm: the jazz historian Ted Gioia weighed in last month at the Web site Jazz.com. “The most likely–indeed the only plausible–explanation for these numbers is that very few new fans have discovered jazz since the 1980s,” Mr. Gioia wrote. “The old fans continue to follow the music, but teenagers and 20-somethings have very little interest in jazz.”

But there’s a wealth of anecdotal evidence to the contrary, as many jazz bloggers and commentators, responding mainly to Mr. Teachout, have been quick to point out. Try dropping in one night this week at the Village Vanguard, where Jason Moran and the Bandwagon are appearing. Or head to the Stone in the East Village, which is likely to hit sweaty capacity for each set programmed by the young drummer-composer Tyshawn Sorey. Or stop by the Highline Ballroom in Chelsea on Friday night for a show by the Bad Plus. Scratch anywhere past the surface and you might begin to wonder whether the likes of Mr. Teachout and Mr. Gioia don’t see young people listening because they don’t know where to look.

The words in question are, of course, “anecdotal evidence.” We’ve been hearing a lot of that lately. It seems that everyone who doesn’t like what Ted Gioia and I had to say went to a jazz club the other night and saw lots of young people there, which means that jazz is alive, well, and thriving. End of story.

Would that it were so simple! Alas, the trouble with Nate Chinen’s piece is that it omits another pair of words that tell a very different story: median age. To quote from my original column:

The median age of adults in America who attended a live jazz performance in 2008 was 46. In 1982 it was 29.

That’s not anecdotal evidence. It’s a finding from a survey jointly conducted by the National Endowment for the Arts and the Census Bureau, and it knocks a mile-wide hole in Chinen’s piece, as well as virtually everything else that’s been written to date about “Can Jazz Be Saved?” The fact that the median age of live jazz audiences in America has gone up by seventeen years in the course of the past quarter-century can mean only one thing: live jazz is simply not attracting enough new young listeners to replace the older ones who are staying home or dying off. Period.

As for the question of whether “the likes of Mr. Teachout and Mr. Gioia” know where to look for young jazz fans, I hasten to point out that I’ve been writing enthusiastically about the Bad Plus ever since 2003, the same length of time as Nate Chinen. I’m also a longtime fan of Medeski, Martin & Wood, another band that Chinen cites in his New York Times piece. More power to both groups, but the fact that they’re drawing young crowds is also beside the point. No amount of anecdotal evidence, however seductive it may seem at first glance, will change the fact that the overall audience for live jazz in America is growing older at an alarmingly rapid rate. Anyone who refuses to face that unpleasant fact–or to bother mentioning it in a piece that seeks to reassure its readers that jazz is in great shape–is part of the problem.

One more thing: what’s happening to jazz now was happening to classical music a decade and a half ago. That’s more or less how long it took for classical performers and presenters to admit the truth about their aging audience and start trying to do something about it. How long will it take before jazz musicians–and journalists–come to the same conclusion?

UPDATE: Says Ted Gioia:

The Times cites “anecdotal evidence” of young people attending jazz events. Meanwhile clubs, festivals, record labels, etc. are shutting down. I guess they need a new infusion of anecdotes.

No kidding.

TT: More gold than lead

Last year I wrote a “Sightings” column for The Wall Street Journal about Studio One Anthology, a six-DVD box set containing seventeen dramas that were originally broadcast live on CBS’ Studio One, one of the best-remembered anthology series of what is now known, rightly or wrongly, as the “golden age” of television:

Last year I wrote a “Sightings” column for The Wall Street Journal about Studio One Anthology, a six-DVD box set containing seventeen dramas that were originally broadcast live on CBS’ Studio One, one of the best-remembered anthology series of what is now known, rightly or wrongly, as the “golden age” of television:

It’s said that series TV today is better than ever before, and that the so-called Golden Age of Television mostly amounted to an endless string of low-budget sitcoms, mysteries and Westerns. As the weaker episodes included in “Studio One Anthology” make all too clear, there’s something to be said for that skeptical point of view. Most of the original plays that aired on the anthology series of the ’50s were mediocre and have been rightly forgotten. But more than a few of them, like “Twelve Angry Men” and “Marty,” were very, very good–and network TV in the ’50s, lest we forget, was also bringing its viewers such blue-chip fare as Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Symphony, Jerome Robbins’ “Peter Pan,” “An Evening with Fred Astaire” and the wildly zany comedy of Sid Caesar and Ernie Kovacs.

Back then, of course, CBS, NBC and ABC still aspired on occasion to offer viewers something more than lowest-common-denominator escapism as part of their daily entertainment diet. Now they mostly play it as safe as skim milk, leaving the risk-taking to cable TV. “Studio One Anthology” is a wistful reminder of how much things have changed since the naïve and hopeful days when television was young.

I felt at the time that Koch Vision, which released Studio One Anthology, would have done better to put out a set that cherry-picked a variety of first-rate TV dramas from the Fifties rather than concentrating on a single series. Now the Criterion Collection is planning to do just that. The Golden Age of Television, scheduled for release on November 24 but now available for preordering, is a three-disc set containing eight important live TV dramas originally telecast between 1953 and 1958, including the original versions of Paddy Chayefsky’s “Marty” and Rod Serling’s “Patterns” and “Requiem for a Heavyweight.” While TV buffs with very long memories will recall that all eight of these programs were rebroadcast on PBS a quarter-century ago and subsequently issued on videocassette, this will be the first time that any of them has been officially released on DVD.

I felt at the time that Koch Vision, which released Studio One Anthology, would have done better to put out a set that cherry-picked a variety of first-rate TV dramas from the Fifties rather than concentrating on a single series. Now the Criterion Collection is planning to do just that. The Golden Age of Television, scheduled for release on November 24 but now available for preordering, is a three-disc set containing eight important live TV dramas originally telecast between 1953 and 1958, including the original versions of Paddy Chayefsky’s “Marty” and Rod Serling’s “Patterns” and “Requiem for a Heavyweight.” While TV buffs with very long memories will recall that all eight of these programs were rebroadcast on PBS a quarter-century ago and subsequently issued on videocassette, this will be the first time that any of them has been officially released on DVD.

I wrote about “Marty” in this space two years ago:

The original hour-long TV version…is lean, direct, and characterful, and Rod Steiger and Nancy Marchand, who play a pair of painfully plain New Yorkers looking for love, are so natural and unaffected that they scarcely seem to be acting at all. It’s easy to see why Marty, though it only aired once on network TV, made a deep and long-lasting impression on all who saw it.

Those comments were based on a single viewing of a used and decidedly battered copy of the videocassette version of “Marty.” I can’t wait to how it looks after being given the Criterion Collection treatment.

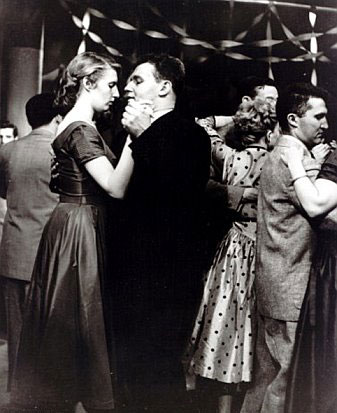

TT: Snapshot

The opening scene of Rod Serling’s “Requiem for a Heavyweight,” starring Jack Palance, Keenan Wynn, and Ed Wynn, originally telecast live on CBS’ Playhouse 90 on October 11, 1956:

(This is the latest in a weekly series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Wednesday.)