When I told Paul Moravec three years ago that I’d love to collaborate with him on an opera, it didn’t occur to me that The Letter would open in the same year that Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong would be published. I’m sure I would have said yes anyway–it was an offer I couldn’t refuse–but I might have thought twice, and maybe even thrice, if I’d known exactly what I was getting into.

The good news is that Pops won’t be coming out until four months after The Letter opens. That doesn’t mean I can simply put Satchmo aside for now and concentrate solely on Santa Fe, of course, though The Letter is rarely far from my mind these days. Paul and I popped up in the annual list of summer-festival highlights published in Sunday’s New York Times, and I also ran across an Associated Press story the other day in which Charles MacKay, the general director of the Santa Fe Opera, announced that the company has been “doing pretty well” despite the current economic difficulties. That tallies with everything I’ve been hearing so far. Ticket sales for The Letter are looking good, and though we’ve encountered a few bumps in the road to opening night, we haven’t hit any potholes.

The good news is that Pops won’t be coming out until four months after The Letter opens. That doesn’t mean I can simply put Satchmo aside for now and concentrate solely on Santa Fe, of course, though The Letter is rarely far from my mind these days. Paul and I popped up in the annual list of summer-festival highlights published in Sunday’s New York Times, and I also ran across an Associated Press story the other day in which Charles MacKay, the general director of the Santa Fe Opera, announced that the company has been “doing pretty well” despite the current economic difficulties. That tallies with everything I’ve been hearing so far. Ticket sales for The Letter are looking good, and though we’ve encountered a few bumps in the road to opening night, we haven’t hit any potholes.

On the other hand, I’ve had to juggle Pops and The Letter more or less simultaneously in recent weeks, and while I have yet to drop any balls on my head, it’s been a near-run thing. Last Tuesday, for instance, Paul and I auditioned a pair of singers, then went straight to a club in midtown Manhattan to give an hour-long presentation on The Letter. The next day I was interviewed twice about Pops, once via e-mail and once on the phone, in preparation for my May 29 appearance at BookExpo America (Benjamin Moser, the alarmingly smart new-books columnist of Harper’s, will be interviewing me on stage that afternoon). I also finished writing an essay about the making of The Letter for the July issue of Commentary. In between these varied activities, I chipped away at the page proofs of Pops, knocked out a Wall Street Journal drama column, went to Brooklyn to see a performance by Propeller of The Merchant of Venice, and started drafting proposals–strictly preliminary, at least for the moment–for three books that I’m giving serious thought to writing.

If you think I’m working too hard, you’re right, and it’s only going to get worse. The only thing that’s keeping me on a fairly even keel is that both The Letter and Pops are basically finished: I still have a certain amount of this-and-that left to do, but the really heavy lifting is now in the hands of the Santa Fe Opera and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Nevertheless, I’m going to be unremittingly busy between now and January, and I find the prospect unnerving, sometimes even scary.

How do I cope? By going to the gym each day, going to bed as early as I can each night, and seizing every opportunity, however brief, to put down the reins and read, watch, or listen to something unrelated to Pops or The Letter. It’s helping, too, that so many of the shows I’m seeing these days are turning out to be exceptionally good. Great art is, among other things, a powerful distraction from the problems of the moment, and it has been a blessed relief to be able to escape into such enveloping theatrical experiences as The History Boys, Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, and The Norman Conquests.

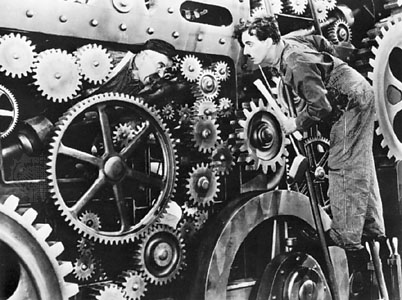

What I can’t do–at least not very often–is lie fallow. That’s something I need to do, but it won’t be possible any time soon. In order to make it all the way from here to January without falling over, I have to pedal as fast as I can. Moreover, I feel guilty every time I complain about being too busy, because I know that the world is full of anxious artists who aren’t nearly busy enough. As I’ve previously had occasion to mention in this space. George Balanchine was once asked why the members of New York City Ballet’s pit orchestra were paid less than New York City’s garbagemen. His answer? “Because garbage stinks.” Nobody has to tell me that my life smells like roses.

The fact that I have an opera opening in July and a book coming out in December is by any reasonable standard a wholly unmixed blessing, and few days pass without my remembering to rejoice at my good fortune. But as Raskolnikov reminds us, “Man grows used to everything–the beast!” I’ll try to remind myself at regular intervals not to be too beastly about being too busy.