I read “Peanuts” every day when I was a boy. In college, though, I stopped reading newspapers other than sporadically, and by the time I got back into the habit years later, I’d lost interest in comic strips. Watching the American Masters TV documentary on Charles Schulz made me curious as to what impression “Peanuts” would make on me now, so I rooted around on the Web and found a site on which it is possible to read the entire 17,897-strip run of “Peanuts,” day by day. I rolled up my sleeves and started clicking my way through 1961, and for a few minutes I responded happily to the rueful charm with which Charlie Brown and his friends grappled with life’s little problems–but soon I lost interest and moved on to other things.

I read “Peanuts” every day when I was a boy. In college, though, I stopped reading newspapers other than sporadically, and by the time I got back into the habit years later, I’d lost interest in comic strips. Watching the American Masters TV documentary on Charles Schulz made me curious as to what impression “Peanuts” would make on me now, so I rooted around on the Web and found a site on which it is possible to read the entire 17,897-strip run of “Peanuts,” day by day. I rolled up my sleeves and started clicking my way through 1961, and for a few minutes I responded happily to the rueful charm with which Charlie Brown and his friends grappled with life’s little problems–but soon I lost interest and moved on to other things.

The problem I had with “Peanuts” is the same problem I have with virtually all serial art: it isn’t meant to be consumed in bulk. A daily comic strip whose installments are free-standing rather than connected by strands of plot is an endless series of moments. To read it once a day is a fleeting pleasure. To read dozens of installments in a single sitting is to realize just how ephemeral that pleasure was.

I’ve tried on other occasions to revisit other works of serial art that gave me pleasure in the past. In 2007, for instance, I tried watching Hill Street Blues reruns once or twice a week. At first I enjoyed the experiment, but before long the same thing happened: even though I saw what I’d seen in the show when it was new, I simply couldn’t make myself watch it on a regular basis. For my generation, part of the point of watching a TV series was its regularity. It was a social event, a communal activity. You structured your week around it, and so did your family and friends. The introduction of the VCR eliminated this iron necessity, and for me it also eliminated much of the attraction of series TV, which I no longer watch.

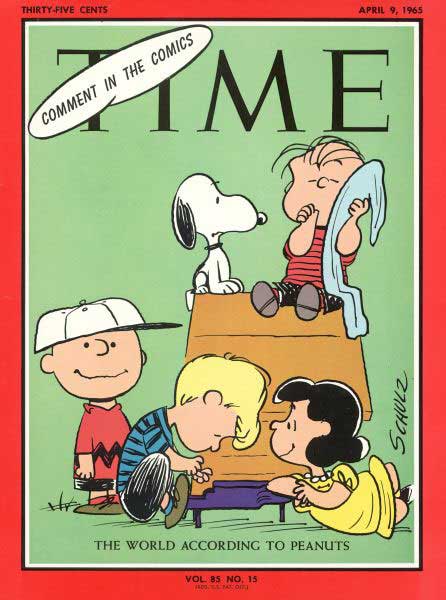

As for “Peanuts,” the documentary reminded me, among other things, of how seriously Schulz’s work was taken in the Sixties. In 1965 Time went so far as to run a portentous cover story declaring “Peanuts” to be something more than a daily treat:

As for “Peanuts,” the documentary reminded me, among other things, of how seriously Schulz’s work was taken in the Sixties. In 1965 Time went so far as to run a portentous cover story declaring “Peanuts” to be something more than a daily treat:

The wry and wistful characters created by Cartoonist Charles M. Schulz have all but come to life for readers in the U.S. and abroad as they demonstrate daily and Sunday an engaging wisdom beyond their years, a simplistic yet somehow impressive understanding of the assorted problems that perplex their elders….Love, hate, togetherness, solitude, the alienation in an age of anxiety–such topics are so deftly explored by Charlie Brown and the rest of the “Peanuts” crew that readers who would not sit still for a sermon readily devour the sermon-like cartoons.

True enough, I suppose, at least in the early years of “Peanuts,” though the strip is widely thought to have grown less interesting as Schulz devoted more and more of his time to the TV specials and marketing ventures that made him unimaginably rich. But even at its best, how good can a four-frame comic strip be? Just for the sake of argument, let’s suppose that Charles Schulz was the modern equivalent of…oh, a French aphorist. This isn’t as absurd a comparison as you might think: the very best “Peanuts” strips have a concentration and simplicity not unlike that of a good aphorism. But how many times can the trick be turned? Even La Rochefoucauld came up short on occasion, and he only left behind seven hundred-odd maxims. It would never have occurred to him to try to be wise once a day for half a century.

I come not to bury good old Charlie Brown, but to note the tendency of a popular culture to overpraise its own passing fancies. We want the things we like to also be good, and if you’ve never seen Hamlet, you’re likely to think that cable TV is better than it really is–which isn’t to say that you should run right out and sell your TV. I spend a fair amount of time watching pretty good movies on TV, time that would doubtless be better spent reading Proust or listening to the St. Matthew Passion were it not for the fact that I find that I can’t grapple with the eternal verities twenty-four hours a day. I like well-made B movies, the same way that I like diner food. The difference is that I’d never write a monograph on corned-beef hash.

We have it on the best of authority that a thing of beauty is a joy forever. But some pleasures are meant to be enjoyed once, set aside, and remembered fondly–and occasionally.

UPDATE: A friend writes:

What was wonderful about “Peanuts” was that it reflected a deep truth about childhood for children that was unavailable anywhere else: that it is a time not of high adventure but often of confusion and anxiety. That’s what made Charlie Brown indelible, but once you recognize this about life in general, it no longer offers the shock of recognition.

I think that’s exactly right. One of the best shots in the PBS documentary was a slow pan down a newspaper comic page circa 1960, showing “Peanuts” in the context of the other strips of the day–a vivid illustration of how different Schulz’s work was from that of his contemporaries, both in subject matter and in visual style. This makes it easier to see why “Peanuts” made so strong an impression at the time.

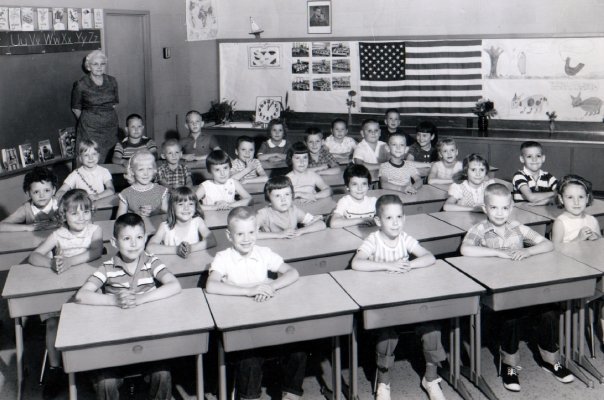

Other things remain unchanged as well. The school that I attended in 1962, Matthews Elementary, is still open for business. It’s one block north of 713 Hickory Drive, the house where I grew up and where my 79-year-old mother still lives. Most of the people in the photo are alive, and some of them can still be found in or near Smalltown, U.S.A., though I haven’t seen any of them for years.

Other things remain unchanged as well. The school that I attended in 1962, Matthews Elementary, is still open for business. It’s one block north of 713 Hickory Drive, the house where I grew up and where my 79-year-old mother still lives. Most of the people in the photo are alive, and some of them can still be found in or near Smalltown, U.S.A., though I haven’t seen any of them for years. A few months ago I posted an excerpt from “Walking Distance,” a 1959 episode of The Twilight Zone in which Gig Young trips over a crack in time, finds himself in the small town where he grew up, and runs into a little boy who turns out to be his younger self. He tries to do what I just imagined doing–and, needless to say, it doesn’t work. Small children know nothing of the future: they barely know the difference between today and tomorrow. What they see is what there is. Do I know better now? I wonder. Samuel Beckett said it: “We have time to grow old. The air is full of our cries. But habit is a great deadener. At me too someone is looking, of me too someone is saying, He is sleeping, he knows nothing, let him sleep on.”

A few months ago I posted an excerpt from “Walking Distance,” a 1959 episode of The Twilight Zone in which Gig Young trips over a crack in time, finds himself in the small town where he grew up, and runs into a little boy who turns out to be his younger self. He tries to do what I just imagined doing–and, needless to say, it doesn’t work. Small children know nothing of the future: they barely know the difference between today and tomorrow. What they see is what there is. Do I know better now? I wonder. Samuel Beckett said it: “We have time to grow old. The air is full of our cries. But habit is a great deadener. At me too someone is looking, of me too someone is saying, He is sleeping, he knows nothing, let him sleep on.”