It’s been a decade since I last set foot in any part of Texas other than an airport. I’ve been wanting to review theater there for the past few years, but until this week I was never able to find a sufficiently compact stretch of time when I could catch more than one worthy-looking show.

Even this trip, short as it was, took some doing. I had to fly from Washington, D.C., to Houston on Saturday, see Main Street Theater’s revival of Clifford Odets’ Awake and Sing! on Sunday afternoon, drive from Houston to Dallas that same night so that I could attend the opening of Theatre Three’s production of Kurt Weill’s Lost in the Stars on Monday, then fly to Kansas City on Tuesday morning for a preview of A Flea in Her Ear. I hate cramming so many shows into so brief a span of time, but there was no way to get around it–the schedules of the three companies that I wanted to see locked together in only one way that fit into the rest of my itinerary–so I made my plans and resigned myself to scurrying.

I spent twenty-one hours in Houston, not nearly long enough to get more than the flimsiest of impressions of a city that I remember only vaguely from my previous trip. It felt sprawling and sleepy on Saturday night, but I have no doubt that appearances were deceiving (especially given the fact that I was sleepy, too). Brazos Bookstore, an independently owned shop to which I made a happy pilgrimage the next morning, is an unmistakable sign of intellectual life, an egghead’s paradise of well-stocked shelves and comfy chairs that left nothing to be desired save for being located in Houston instead of on the Upper West Side of New York.

Since I only had time to visit one other cultural landmark before heading for the theater on Sunday, I decided to return to the Rothko Chapel, which I saw for the first time when I went to Houston in 1998 to interview Francesca Zambello for Time. It struck me then as bleak and forbidding, a monochrome monument to everything that is least inviting about modernism, and I can’t say I felt all that different the second time around.

Since I only had time to visit one other cultural landmark before heading for the theater on Sunday, I decided to return to the Rothko Chapel, which I saw for the first time when I went to Houston in 1998 to interview Francesca Zambello for Time. It struck me then as bleak and forbidding, a monochrome monument to everything that is least inviting about modernism, and I can’t say I felt all that different the second time around.

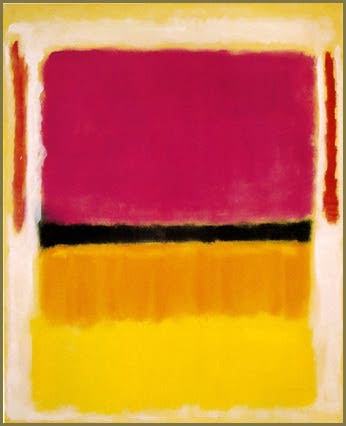

Misleading though it can be to read an artist’s life into his work, I’m not greatly surprised that the Rothko Chapel was created by a man who committed suicide a year before it opened. I say this as one who loves Mark Rothko’s paintings of the late Forties and early Fifties passionately. In those days he was full of life, spilling over with the bold, high-key colors that he first saw in the work of Pierre Bonnard. But something seems to have gone badly wrong by the time he got around to painting the Rothko Chapel murals (though there are plenty of critics and scholars who beg to differ).

Misleading though it can be to read an artist’s life into his work, I’m not greatly surprised that the Rothko Chapel was created by a man who committed suicide a year before it opened. I say this as one who loves Mark Rothko’s paintings of the late Forties and early Fifties passionately. In those days he was full of life, spilling over with the bold, high-key colors that he first saw in the work of Pierre Bonnard. But something seems to have gone badly wrong by the time he got around to painting the Rothko Chapel murals (though there are plenty of critics and scholars who beg to differ).

To be sure, the chapel bills itself as “a place alive with religious ceremonies of all faiths,” and countless religious and quasi-religious groups use it for their various purposes. A delegation from Yoga for Peace was setting up shop when I arrived on Sunday morning. But the black-on-black panels in whose fathomless darkness they labored seemed to mock their smiling certitude, and I could all but hear Matthew Arnold’s “melancholy, long, withdrawing roar” in the middle distance as I watched them make ready to glorify Krishna.

It was a relief to escape from the spiritual chill of the chapel to the furious warmth of the quarreling Jewish family that Clifford Odets portrayed in Awake and Sing! As I wrote in The Wall Street Journal apropos of the 2006 Broadway revival of Odets’ greatest play:

“Awake and Sing!” is the original Jewish-mom kitchen-sink family drama, complete with stock characters, a creaky plot and a happy ending that reeks of socialist realism–none of which matters in the least. The point of the play is the dialogue, which crackles with the near-stenographic exactitude of an artist who had an exquisitely precise ear for the speech of the lost world into which he was born: “I can’t take a bite in my mouth no more.” “You’ll excuse my expression, you’re bughouse.” “Don’t yell in my ears. I hear.” In Odets’ hands everyday talk becomes musical, and you hang breathlessly on each line. It’s as if Anton Chekhov had paid a visit to the Lower East Side.

From the Lower East Side to the wastelands of Texas: the highway between Houston and Dallas is flat and tedious, and no one drives it who doesn’t have to. I suppose I could have flown, but it was somewhat more convenient to rent a car at the Houston airport and drop it off in Dallas, so I hit the road again as soon as Awake and Sing! was over, driving for the better part of five hours and pausing only to dine on chicken-fried steak and sweet tea at Sam’s Restaurant, a no-nonsense oasis just past the middle of nowhere.

From the Lower East Side to the wastelands of Texas: the highway between Houston and Dallas is flat and tedious, and no one drives it who doesn’t have to. I suppose I could have flown, but it was somewhat more convenient to rent a car at the Houston airport and drop it off in Dallas, so I hit the road again as soon as Awake and Sing! was over, driving for the better part of five hours and pausing only to dine on chicken-fried steak and sweet tea at Sam’s Restaurant, a no-nonsense oasis just past the middle of nowhere.

It should have been a painfully boring trip, but I ended up enjoying most of it. Barreling down a long, straight stretch of road at eighty miles an hour is one of the most mentally restful activities I know, especially when you’ve been spending too much time juggling too many responsibilities. I only wish I’d thought to bring along some suitable music: Bob Wills and Ray Price would have been ideal, but the car radio offered only Christian rock and hip-hop, so I opted for incongruity and popped The John Kirby Sextet: Complete Columbia and RCA Victor Recordings into the CD player as I made my way to Dallas.

(To be continued)