I wrote this “Sightings” column for The Wall Street Journal three years ago. Many of my friends snorted at the time. Now that the rest of the world has caught up with me, perhaps it’s worth revisiting what I had to say in 2006.

* * *

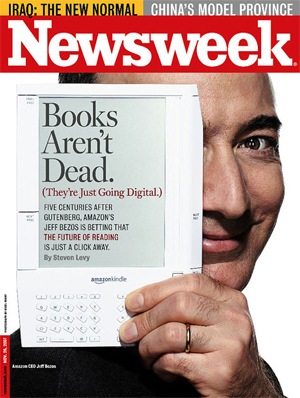

The e-book is back. So are the technophobes who swear it’ll never catch on. They were right last time, and they might be right this time, too. Sooner or later, though, they’ll be wrong–and when they are, your life will change.

The word “e-book” is short for “electronic book.” The concept isn’t new–the complete texts of countless classics have long been available on the Web in digitized form. (Seventeen thousand of them can be downloaded for free at www.gutenberg.org.) The catch is that until now, there hasn’t been a user-friendly way to read e-books. Few people enjoy reading book-length documents on a conventional computer screen, and though hand-held e-book readers went on the market six years ago, they were insufficiently convenient to use and failed to interest the book-buying public.

The word “e-book” is short for “electronic book.” The concept isn’t new–the complete texts of countless classics have long been available on the Web in digitized form. (Seventeen thousand of them can be downloaded for free at www.gutenberg.org.) The catch is that until now, there hasn’t been a user-friendly way to read e-books. Few people enjoy reading book-length documents on a conventional computer screen, and though hand-held e-book readers went on the market six years ago, they were insufficiently convenient to use and failed to interest the book-buying public.

Now Sony has announced plans to market a paperback-sized e-book reader that makes use of E Ink, a new display technology whose makers say it duplicates “the experience of reading from paper.” The Sony Reader, which fits comfortably in one hand, will hold hundreds of e-books in its memory, and its internal battery allows for 7,500 page turns per charge.

It remains to be seen whether the Sony Reader and E Ink are capable of delivering on their fine-sounding technological promises. But Sony has made another promise that is at least as significant: It will also open an iMusic-style online store from which purchasers can download e-books as easily as they download music onto their iPods. Three major publishers, HarperCollins, Random House and Simon & Schuster have agreed to sell their books through Sony, and HarperCollins and Simon & Schuster plan to make their entire backlists available for downloading as soon as they negotiate royalty rights with the authors.

If the Sony Reader (which goes on sale this spring) takes off where previous ventures fell flat, it will be because Sony is offering what marketers call an “end-to-end” solution to the problem of the e-book. That kind of one-stop shopping is what made Apple’s iPod so successful: You don’t just buy the iPod itself, but an easy-to-use system that allows you to download any one of tens of thousands of popular songs within minutes of taking your iPod out of the box.

So will it fly? I don’t know. Still, I’m certain that something like the Sony Reader will catch on, if not this year then in a short time. The phenomenal success of the iPod strongly suggests that many, perhaps most consumers are ready to start buying digital books on the Web and storing and reading them electronically.

And what happens after that? It goes without saying that the economic impact of the e-book on publishers and booksellers will be dramatic (I wouldn’t want to own a brick-and-mortar bookstore these days). But I’m more interested in how the e-book will affect the way we read–and write. New technologies, after all, change art, often in profound and unpredictable ways. I doubt the inventor of the electric guitar foresaw Jimi Hendrix, any more than Thomas Edison foresaw chick flicks. The only thing of which you can be certain is that the existence of the e-book will cause the authors of the 21st century to go about their business very differently than did their 20th-century predecessors.

Many of these differences will arise from the way in which the e-book encourages self-publishing. Best-selling novelists, for instance, will soon be in a position to “publish” their own books, pocketing all the profits–but so will niche-market authors whose books don’t sell in large enough quantities to interest major publishers.

Might the e-book make the writing of serious literary fiction more economically viable? Consider the experience of Maria Schneider, the jazz composer whose CDs are sold exclusively on her Web site, www.mariaschneider.com. Ms. Schneider uses ArtistShare, a new Web-based technology that makes it easier for musicians to sell self-produced recordings online. Not only did she win a Grammy for her first ArtistShare release, “Concert in the Garden,” but she kept all the proceeds as well. Several other well-known jazz musicians, including the guitarist Jim Hall and the trombonist Bob Brookmeyer, have since signed up with ArtistShare, which frees them from the need to compromise with money-conscious record-company executives. Will e-books have a similarly liberating effect on authors? I wouldn’t be surprised.

Yes, I miss the bookstores of my youth, and I’m sure I’ll miss the handsomely bound volumes that fill the shelves in my apartment as well (though I won’t miss dusting them, or toting them around by the half-dozen whenever I go on vacation). The printed book is a beautiful object, “elegant” in both the aesthetic and mathematical senses of the word, and its invention was a pivotal moment in the history of Western culture. But it is also a technology–a means, not an end. Like all technologies, it has a finite lifespan, and its time is almost up.

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City