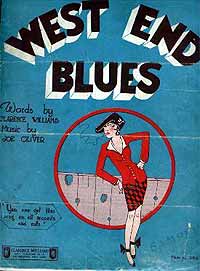

“West End Blues” is Louis Armstrong’s best-known recording. Made in 1928, it opens with a spectacular unaccompanied trumpet cadenza that I discuss in detail in Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong:

“West End Blues” is Louis Armstrong’s best-known recording. Made in 1928, it opens with a spectacular unaccompanied trumpet cadenza that I discuss in detail in Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong:

“West End Blues,” recorded on June 28, starts with a surprise, an unaccompanied cadenza in which Armstrong snaps out four biting quarter notes by way of fanfare, then vaults upward through a chain of interlocking triplet arpeggios to a fiery high C embellished with a touch of vibrato. It was the most technically demanding passage to have been recorded by a jazz trumpeter up to that time, and for this reason alone it was bound to have displeased the old-school New Orleans musicians of Armstrong’s youth, one of whom grumbled that “because Louis was up North making records and running up and down like he’s crazy don’t mean that he’s that great. He is not playing cornet on that horn; he is imitating a clarinet. He is showing off.” Armstrong admitted that he had aspired when young to the facility of the great New Orleans clarinetists: “I was just like a clarinet player, like the guys run up and down the horn nowadays, boppin’ and things.” But his introduction to “West End Blues” has at least as much in common with the florid bel canto cadenzas he had heard in the operatic recordings of Amelita Galli-Curci and Luisa Tetrazzini, and listeners acquainted with turn-of-the-century American band music will also spot the mark of the elaborate unaccompanied passages in the solos of Herbert L. Clarke, John Philip Sousa’s star cornetist, several of whose records Armstrong owned and cherished. “I’ve heard trumpet solos from 1908 up to the present day–Herbert Clarke and all those boys that really used to blow them horns and it sounds like it was recorded yesterday,” he told Leonard Feather in 1954….

Everybody who knows about jazz knows about “West End Blues.” I doubt, though, that most people know where the song, written by Joe Oliver, Armstrong’s mentor, got its name. Nowadays West End is a lakefront neighborhood of New Orleans, but in Armstrong’s time it was a popular summer resort and amusement park on the shore of Lake Pontchartrain that looked like this:

Not far from West End was the Pontchartrain Beach Amusement Park, the place where Mitch takes Blanche DuBois on a date in Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire. The stage directions give the clue: “They have probably been out to the amusement park on Lake Pontchartrain, for Mitch is bearing, upside down, a plaster statuette of Mae West, the sort of prize won at shooting-galleries and carnival games of chance.”

Needless to say, the scene pictured above vanished long ago, and what remained of West End Park was destroyed at last by Hurricane Katrina. But now that I’ve seen that delicately tinted period postcard, I’ll never be able to hear “West End Blues” without imagining a happy crowd of revelers clustered around a Ferris wheel.