Time was when the American musical looked and sounded very different from the Disney-style shows that now dominate Broadway. Its subject matter was (usually) more traditional, its musical language as yet untouched by the rock-and-roll revolution that was to transform American popular culture. Yet the standard musical-comedy repertoire still consists in the main of works that were written before Stephen Sondheim tore up the rules in 1970 with Company. Needless to say, most of the shows that preceded Company were forgettable commodities, but a fair number of them are both theatrically effective and musically distinguished, which is why they continue to be revived.

I see a good many pre-1970 musicals as part of my duties as drama critic of The Wall Street Journal, and it occurred to me the other day to draw up a list of the best ones. Here, then, are the fifteen American musicals that I believe to be of indisputably permanent interest:

• Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II, Show Boat (1927). The first Broadway musical in which book and score were fully integrated, Show Boat remains viable to this day, though it is rarely revived, presumably for reasons of race-related political correctness. Fortunately, virtually all of the show’s essence comes through clearly in James Whale’s splendid 1936 film version, which is mysteriously unavailable on DVD but pops up from time to time on Turner Classic Movies. David Thomson calls it “wonderful,” and he’s right. See it and marvel.

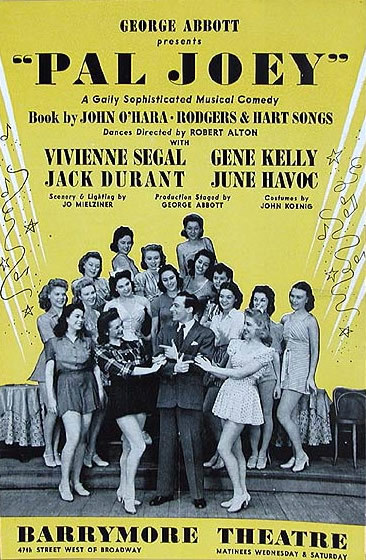

• Richard Rodgers, Lorenz Hart, and John O’Hara, Pal Joey (1940). The recent Broadway revival of Pal Joey was a slicked-up, watered-down caricature of the original show, which was arguably the first truly modern musical to open on Broadway. The real Pal Joey is as corrosively cynical as Billy Wilder at his nastiest, which undoubtedly explains why it failed to go over in 1940, even though Rodgers and Hart wrote a first-rate score full of standards-to-be like “I Could Write a Book” and “Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered.” No original-cast album was made, alas, but Columbia Records taped a studio-only version of the score in 1950 that comes reasonably close to what Broadway audiences heard–and misunderstood–a decade earlier.

• Richard Rodgers, Lorenz Hart, and John O’Hara, Pal Joey (1940). The recent Broadway revival of Pal Joey was a slicked-up, watered-down caricature of the original show, which was arguably the first truly modern musical to open on Broadway. The real Pal Joey is as corrosively cynical as Billy Wilder at his nastiest, which undoubtedly explains why it failed to go over in 1940, even though Rodgers and Hart wrote a first-rate score full of standards-to-be like “I Could Write a Book” and “Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered.” No original-cast album was made, alas, but Columbia Records taped a studio-only version of the score in 1950 that comes reasonably close to what Broadway audiences heard–and misunderstood–a decade earlier.

• Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II, Oklahoma! (1943). As far as most theatergoers are concerned, modern musical comedy starts with Oklahoma! It’s effective to the point of infallibility–even amateurs can make it work–though the 1955 wide-screen film version is more than a little bit overblown. If you know only the movie, you’ll be surprised by how much more touching Oklahoma! is on stage.

• Leonard Bernstein, Betty Comden, and Adolph Green, On the Town (1944). I have yet to see a successful stage revival of On the Town, and the popular 1949 film version is a what-were-they-thinking stinker (MGM scrapped most of the original songs and dances). Be that as it may, it’s a truly great show, a sophisticated melding of music and choreography that to my mind is more artistically satisfying than West Side Story, heretical though that opinion may sound to most people, Mrs. T very much included.

• Irving Berlin, Dorothy Fields, and Herbert Fields, Annie Get Your Gun (1946). Berlin’s other musicals are dramatically inert and so are never revived, but this one continues to ring the gong effortlessly. Never before or since has a Broadway composer written a score with a wider hit-to-filler ratio.

• Cole Porter, Bella Spewack, and Samuel Spewack (after Shakespeare), Kiss Me, Kate (1948). Like Berlin, Porter learned his craft in the pre-Oklahoma! era, but managed late in life to write one show whose book is as dramatically sound as its score is musically impeccable. Even Evelyn Waugh, than whom few customers were tougher, loved Kiss Me, Kate. So do I, and it’s about due for another Broadway revival, though it’ll be hard to better Michael Blakemore’s 1999 staging. (As usual, skip the movie–it has its moments, but not enough to make it fly.)

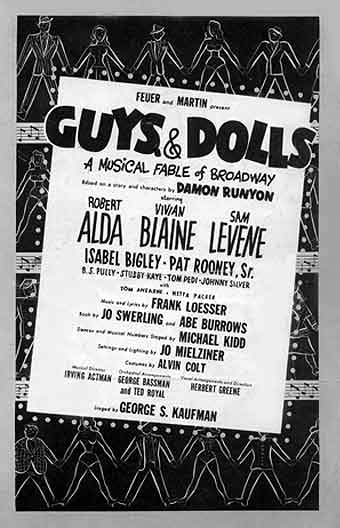

• Frank Loesser, Abe Burrows, and Jo Swerling, Guys and Dolls (1950). If there’s a flawless Broadway musical, this is it. Not only is every song a polished gem, but the book, like that of Kiss Me, Kate, works like a charm. Stay as far away as possible from the current Broadway revival, which somehow manages, like the appalling 1955 film version, to get just about everything wrong about a show whose authors took infinite care to get everything right.

• Frank Loesser, Abe Burrows, and Jo Swerling, Guys and Dolls (1950). If there’s a flawless Broadway musical, this is it. Not only is every song a polished gem, but the book, like that of Kiss Me, Kate, works like a charm. Stay as far away as possible from the current Broadway revival, which somehow manages, like the appalling 1955 film version, to get just about everything wrong about a show whose authors took infinite care to get everything right.

• Frederick Loewe and Alan Jay Lerner (after George Bernard Shaw), My Fair Lady (1956). Is My Fair Lady better than Pygmalion? I (sometimes) think so, as do a surprisingly large number of Shavians. I’m not usually a fan of the shows of Lerner and Loewe, most of which strike me as a bit on the sugary side, but My Fair Lady is an exception, a consummately well-made piece of stage carpentry whose operetta-like score is resplendently lovely. The film is awfully good, too, though it does go on a bit.

• Leonard Bernstein, Stephen Sondheim, and Arthur Laurents, West Side Story (1957). Jerome Robbins’ choreography isn’t quite indispensable to the effect of West Side Story, but it comes damned close. Fortunately, Robbins supervised the filming of most of the dance numbers in the 1961 film version, which is not entirely successful–the casting is erratic–but still comes across with tremendous force when seen on a large screen. Yes, it’s sentimental, but so what? Even as is, it still beats hell out of the current Broadway revival, in which Arthur Laurents mistakenly tried to toughen the show up, in the process distorting Robbins’ dances almost beyond recognition.

• Meredith Willson, The Music Man (1957). The 1961 movie version of this irresistibly corny show is the most representative and effective film of a Broadway musical ever made, give or take Show Boat and How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying. It has a few flaws–I could do without Buddy Hackett–but you can easily see why Robert Preston’s magnetic stage performance made him a star overnight.

• Harvey Schmidt and Tom Jones, The Fantasticks (1960). I called The Fantasticks “the perfect musical” in my Wall Street Journal review of the 2006 revival, and I haven’t changed my mind. Modest, simple, and surprisingly subtle, the best of all possible small-scale musicals hasn’t aged a day since it opened off Broadway a half-century ago.

• Jule Styne, Stephen Sondheim, and Arthur Laurents, Gypsy (1959). The great dance critic Arlene Croce called Gypsy “the best Broadway show I ever saw…a masterpiece of poetic theater and radical design.” None of these qualities made it into the maladroit 1962 film version, but the original-cast album, like the show’s four successful Broadway revivals, leaves no doubt of why Gypsy is widely regarded as the ultimate musical comedy, a vade mecum of everything that makes musicals work.

• Frank Loesser, Abe Burrows, Jack Weinstock, and Willie Gilbert, How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying (1961). The 1967 film version is close to ideal, and it also preserves the justly celebrated stage performances of Robert Morse and Rudy Vallée. The show itself is a wonder, one of the last indisputably classic pre-Sondheim Broadway musicals, as well as the only one that engages with postwar American life in a witty, clear-eyed way.

• Jerry Bock, Sheldon Harnick, and Joe Masteroff, She Loves Me (1963). More a cult show than a full-fledged hit, She Loves Me is, like My Fair Lady, a near-operetta that is directly comparable in quality to The Shop Around the Corner, the fluffy Ernst Lubitsch film on which it is closely based. Unlike any other cult musical, though, it has been successfully revived both on Broadway and in numerous regional-theater productions, and I dare say that it has more fans now than when it was new.

• Jerry Bock, Sheldon Harnick, and Joseph Stein, Fiddler on the Roof (1964). Fiddler might just be the quintessential Broadway musical, more unabashedly popular (and poignant) than Gypsy and almost as well crafted. Unlike West Side Story, it doesn’t need Jerome Robbins’ dances to make its effect, though they rank high among his choreographic landmarks.

Needless to say, this short list doesn’t exhaust the roster of revivable classics, some of which, like A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, 110 in the Shade, Peter Pan, and Wonderful Town, are of very high quality. Most of the rest of the really big golden-age shows, however, are theatrically effective but ultimately uninteresting–Bye Bye Birdie, Damn Yankees, Man of La Mancha, and The Pajama Game come to mind–while the cult shows, of which Anyone Can Whistle, Fiorello!, House of Flowers, and The Yearling head my personal list, typically have striking scores that are sunk by problematic books.

What else is missing? Porgy and Bess, obviously, and for the obvious reason, which is that it’s an opera, not a musical. Nor did any of the Gershwin brothers’ other shows make my list. I don’t think they work on stage, not even Of Thee I Sing, which was revolutionary in 1931 but is creaky now. Likewise Irving Berlin and Cole Porter, who only wrote one show apiece that is revivable today. As for the later Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals, their books are too earnest for my taste, though Carousel and The King and I can be enlivened by imaginative direction. Cabaret is the only pre-Company musical that works better on screen than on the stage. (The book is full of holes.) I omitted Candide, everybody’s favorite cult musical, because it has no definitive stage version–we remember it solely because of the score–and I passed over Hello, Dolly!, one of the most popular shows ever to hit Broadway, because Jerry Herman’s songs are catchy but banal.

And there you have it: the permanent repertory of the Terry Teachout Musical Theater Company. I’d be more than happy to see and review these fifteen shows in regular rotation each year for the rest of my working life–though it happens that I’ve only had the opportunity to write about ten of them in my Wall Street Journal drama column. So if you’re the artistic director or publicist of a professional theater company that’s planning to mount Show Boat, On the Town, Annie Get Your Gun, The Music Man, or How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying next season, kindly drop me a line. It’s never too soon to get your bid in.