Ezio Pinza and Mary Martin sing “Some Enchanted Evening” on TV in 1954:

(This is the latest in a weekly series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Wednesday.)

Archives for March 2009

TT: Almanac

“The slaughter of reputations in the cultural life of this country is scandalous. (It’s funny how, as I write it, the very phrase ‘cultural life’ strikes me as archaie.) The fact is, all too few reputations remain intact among us. We erase history even as we make it–‘we cancel our experience.’ Reverence is rare, even for the most renowned; instead, there is a fundamental indifference toward those vociferiously touted, and the ones who have ‘made it’ are soon enough unmade.”

Harold Clurman, All People Are Famous (Instead of an Autobiography)

TT: Long ago and far away

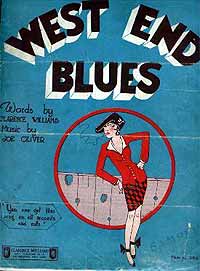

“West End Blues” is Louis Armstrong’s best-known recording. Made in 1928, it opens with a spectacular unaccompanied trumpet cadenza that I discuss in detail in Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong:

“West End Blues” is Louis Armstrong’s best-known recording. Made in 1928, it opens with a spectacular unaccompanied trumpet cadenza that I discuss in detail in Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong:

“West End Blues,” recorded on June 28, starts with a surprise, an unaccompanied cadenza in which Armstrong snaps out four biting quarter notes by way of fanfare, then vaults upward through a chain of interlocking triplet arpeggios to a fiery high C embellished with a touch of vibrato. It was the most technically demanding passage to have been recorded by a jazz trumpeter up to that time, and for this reason alone it was bound to have displeased the old-school New Orleans musicians of Armstrong’s youth, one of whom grumbled that “because Louis was up North making records and running up and down like he’s crazy don’t mean that he’s that great. He is not playing cornet on that horn; he is imitating a clarinet. He is showing off.” Armstrong admitted that he had aspired when young to the facility of the great New Orleans clarinetists: “I was just like a clarinet player, like the guys run up and down the horn nowadays, boppin’ and things.” But his introduction to “West End Blues” has at least as much in common with the florid bel canto cadenzas he had heard in the operatic recordings of Amelita Galli-Curci and Luisa Tetrazzini, and listeners acquainted with turn-of-the-century American band music will also spot the mark of the elaborate unaccompanied passages in the solos of Herbert L. Clarke, John Philip Sousa’s star cornetist, several of whose records Armstrong owned and cherished. “I’ve heard trumpet solos from 1908 up to the present day–Herbert Clarke and all those boys that really used to blow them horns and it sounds like it was recorded yesterday,” he told Leonard Feather in 1954….

Everybody who knows about jazz knows about “West End Blues.” I doubt, though, that most people know where the song, written by Joe Oliver, Armstrong’s mentor, got its name. Nowadays West End is a lakefront neighborhood of New Orleans, but in Armstrong’s time it was a popular summer resort and amusement park on the shore of Lake Pontchartrain that looked like this:

Not far from West End was the Pontchartrain Beach Amusement Park, the place where Mitch takes Blanche DuBois on a date in Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire. The stage directions give the clue: “They have probably been out to the amusement park on Lake Pontchartrain, for Mitch is bearing, upside down, a plaster statuette of Mae West, the sort of prize won at shooting-galleries and carnival games of chance.”

Needless to say, the scene pictured above vanished long ago, and what remained of West End Park was destroyed at last by Hurricane Katrina. But now that I’ve seen that delicately tinted period postcard, I’ll never be able to hear “West End Blues” without imagining a happy crowd of revelers clustered around a Ferris wheel.

TT: Almanac

“If an American had the choice between encountering God and attending a lecture on Him, he would choose the lecture.”

Alfred Stieglitz (quoted in Harold Clurman, All People Are Famous)

CAAF: Also, they’re “furry”

A great, cool thing happened this morning. Lately, before I get started with work in the morning, I’ve been doing this exercise meant to improve my “precision of natural description” — which means, basically, I stare at some point in the yard and try to describe what I see as fully as I can without lapsing into metaphor. It’s all very low stakes. Just something to do while waking up and drinking coffee. But last night I was reading Martin Chuzzlewit before bed and was struck by this description of a landscape near Salisbury:

On the motionless branches of some trees, autumn berries hung like clusters of coral beads, as in some fabled orchards where the fruits were jewels; others, stripped of all their garniture, stood, each the centre of its little heap of bright red leaves, watching their slow decay; others again, still wearing theirs, had them all crunched and crackled up, as though they had been burnt; about the stems some were piled, in ruddy mounts, the apples they had borne that year; while others (hardy evergreens this class) showed somewhat stern and gloomy in their vigour, as charged by nature with the admonition that it is not to her more sensitive and joyous favourites she grants the longest term of life.

The passage is precise about the different stages of the berries (maybe too precise), but it’s the line about the evergreens as “stern and gloomy in their vigour” that leapt out — because it’s impressionistic but true. That is how evergreens come across in a crowd. And so this morning I was staring particularly hard at the trees in our backyard trying to describe them a little less lazily than usual. It was early and still dark out. There’s been rain so it was misty, especially around the woods, and as I was staring at the trees (“tall, green, leafy”) a snout materialized in the mist, then some strong shoulders — and well, it was not a dog, it was a bear (“big and brown”).

Bears frequent our neighborhood — as I’ve mentioned, we live near the forest, and there’s an orchard up the street that the bears are also fond of — but I haven’t seen one in a couple years. The neighborhood itself is fairly Southern suburban: a lot of ranches and split-levels, school buses and pick-ups, a couple bouffants, one excellent mullet, several aged beagles and a pit bull named Ashanti. I took a walk the other week and the two most pronounced scents in the air were fabric softener and cigarette smoke, which just about sums it up. So it’s still surprising, even though it shouldn’t be, whenever a bear comes ambling through. What I was mostly surprised about, though, is how electric I went on seeing it, even though I was inside the house. Also surprising — and this amazes me every time I’ve seen one — is how fast a bear can clip along, despite its size, even when, as this one was, it’s in no particular hurry. You want to say a bear “lumbers” but it doesn’t.

One last link to Martin Chuzzlewit. Last week I finished Great Expectations and was casting around for which Dickens to read next. I chose MC because of this line that I had read somewhere: “For there is a poetry in wildness, and every alligator basking in the slime is in himself an Epic, self-contained.” Which if it is true of alligators is also true of bears.

CAAF: Afternoon coffee

• Laila Lalami weighs in on The Kindly Ones for the LA Times. Over at The Literary Saloon, they’ve been tracking the novel’s antipodal reception in the press; if you’re at all interested you’ll particularly want to read Daniel Mendelsohn’s essay in the New York Review of Books. Also noteworthy and via the Lit Saloon: Translator Charlotte Mandell describes the process she followed to translate the novel from the French.

• “Read Cecil’s Life of Cowper. … Very bad. But what a life! It depressed & terrified me. How did he ever manage to write such bad poetry?”

TT: De la crème

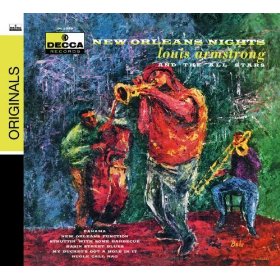

Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong, my forthcoming biography, includes an appendix of thirty “key recordings” by Armstrong, all of which figure prominently in the text of the book and can be downloaded from iTunes. Here’s the list:

1. “Chimes Blues” (Gennett, 1923, with King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band)

2. “Texas Moaner Blues” (OKeh, 1924, with Sidney Bechet

and Clarence Williams’ Blue Five)

3. “St. Louis Blues” (Columbia, 1925, with Bessie Smith)

4. “Heebie Jeebies” (OKeh, 1926, with the Hot Five)

5. “Cornet Chop Suey” (OKeh, 1926, with the Hot Five)

6. “Potato Head Blues” (OKeh, 1927, with the Hot Seven)

7. “Hotter Than That” (OKeh, 1927, with Lonnie Johnson and the Hot Five)

8. “West End Blues” (OKeh, 1928, with Earl Hines and the Hot Five)

8. “West End Blues” (OKeh, 1928, with Earl Hines and the Hot Five)

9. “Weather Bird” (OKeh, 1928, with Earl Hines)

10. “I Can’t Give You Anything but Love” (OKeh, 1929)

11. “Ain’t Misbehavin'” (OKeh, 1929)

12. “Sweethearts on Parade” (OKeh, 1930)

13. “Star Dust” (OKeh, 1931, first take)

14. “I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues” (Victor, 1933)

15. “Darling Nelly Gray” (Decca, 1937, with the Mills Brothers)

16. “Jubilee” (Decca, 1938)

17. “Struttin’ With Some Barbecue” (Decca, 1938)

18. “Jeepers Creepers” (Decca, 1939, with Sid Catlett)

19. “Sleepy Time Down South” (Decca, 1941)

20. “Snafu” (Victor, 1946, with the Esquire All-American 1946 Award Winners)

21. “Back o’ Town Blues” (Victor, 1947, with Jack Teagarden, Bobby Hackett, and Sid Catlett, recorded live at New York’s Town Hall)

22. “Blueberry Hill” (Decca, 1949)

23. “New Orleans Function” (Decca, 1950, with Earl Hines, Jack Teagarden, and the All Stars)

23. “New Orleans Function” (Decca, 1950, with Earl Hines, Jack Teagarden, and the All Stars)

24. “You Rascal You” (Decca, 1950, with Louis Jordan and His Tympany Five)

25. “Mack the Knife” (Columbia, 1955, with the All Stars)

26. “King of the Zulus” (Decca, 1957, with the All Stars, from Satchmo: A Musical Autobiography)

27. “How Long Has This Been Going On?” (Verve, 1957, with the Oscar Peterson Trio, from Louis Armstrong Meets Oscar Peterson)

28. “Black and Tan Fantasy” (Impulse, 1961, with Duke Ellington and the All Stars, from Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington)

29. “Summer Song” (Columbia, 1961, with Dave Brubeck, from The Real Ambassadors)

30. “Hello, Dolly!” (Kapp, 1963, with the All Stars)

TT: Almanac

“I understood now why I loved to go to the theatre, even when I did not respect it in the way I respected the very idea of a concert. When I had been contemptuous of the stage I had generally been displeased by the emptiness of the plays. But I loved to go to the theatre because the presence of the actors–their aliveness, the closeness of the audience, and the anticipation of a communion between all of them in terms of imagination, embodied through their actual movement in tangible space–was the very flower of large social contact, even when the occasion for this contact, in terms of literature, was a silly anecdote. At each performance in the theatre something happened between contemporaries that was a deep pleasure for those who loved the human vibration of people in their common play and enthusiasm.”

Harold Clurman, The Fervent Years: The Group Theatre and the Thirties