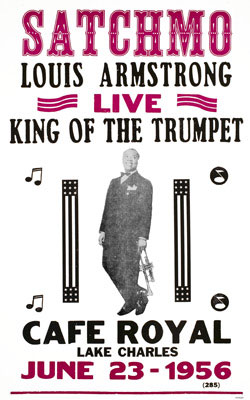

A friend writes in response to my recent posting about my Louis Armstrong biography:

A friend writes in response to my recent posting about my Louis Armstrong biography:

“Sooner or later, everyone who interviews me about Pops will ask some variation on this question: Why do we need another book about Satchmo? The short answer is that I am…”

Terry.

I stopped reading (at the ellipsis).

The short answer is (as if I were you, speaking): Because I never wrote one before.

I would believe this about any “subject” and about any writer. There may be a million books about Mahler, but someday, SOMEDAY, there is going to be one written by a person who somehow actually speaks to ME! And THAT will be the Mahler bio I turn to again and again. Same with Louis Armstrong. There may be a million books, but I’ve not read a single one. There NEEDS to be another (another, another, and another) book about singularly interesting people, subjects, topics…because “the greatest book” or “definitive version” is not universal. I just do NOT believe it can be so. Your book needs to be written because you, your voice, will speak to people who a) may never have read about Louis Armstrong, b) know every book on Armstrong, but read yours and say, wow, what a great new facet!, c) know every book, and think yours sucks, and thus are inspired to TALK ABOUT IT, and WHY. And there’s probably d) e) and f) too.

O.K. So now I’ll go actually read your post….

My friend is a bit of an idealist, but I happen to agree with her, though I’d put it somewhat differently: there’s no such thing as a definitive biography of a great man. There can’t be. A great man (or woman) is too big to cram into a book-sized box. The best that you can do is offer a summary of the current state of knowledge about him, written from your own point of view–but you can never know everything there is to know. The day after your book is published, somebody may dig up an immensely important fact that you missed, or interpret the facts that you dug up in a way that makes more sense than your version. Biographical understanding is a journey without a destination, only stops along the way.

For this reason I, too, believe that there ought to be many books about Armstrong. As I recently said in an e-mail to Ricky Riccardi, the indefatigable Armstrong blogger who is currently writing a book about Armstrong’s later years:

I hope that Pops provides stimulus for the emerging monographic literature on Louis Armstrong. That your book will come out a year after mine seems to me enormously appropriate and significant–it will be a signal that specific aspects of Armstrong’s life and work are now seen as no less deserving of full-length treatment than, say, Matisse’s later years. If that wish comes true, then I’ll undoubtedly want to publish a revised edition of Pops in, say, 2030.

I should live so long!