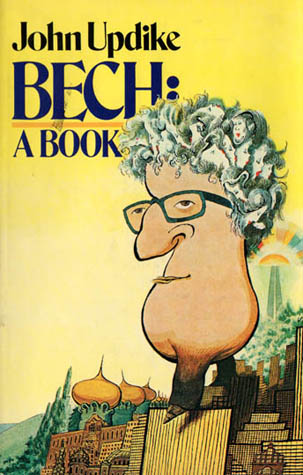

I never succeeded in engaging with John Updike’s work, and I’ve always assumed that the fault is mine. Throughout my lifetime he was the very model of a modern man of letters, a quintessentially professional writer pur sang who tried his hand at everything (he even wrote a play, Buchanan Dying) and was widely and impressively varied in his interests. I couldn’t help but admire his seriousness and industry, and from time to time I’d give him another try, never to any avail. His prose style in fiction struck me as unpleasingly gray and thick, his essays and reviews as fluent but essentially conventional. The only book of his I really liked was Bech: A Book, and I didn’t like it well enough to hang onto my copy when I pruned my library a few years ago. Yet time and again friends whose taste I trusted assured me that I was wrong about Updike, and insisted that I should try, try again.

I never succeeded in engaging with John Updike’s work, and I’ve always assumed that the fault is mine. Throughout my lifetime he was the very model of a modern man of letters, a quintessentially professional writer pur sang who tried his hand at everything (he even wrote a play, Buchanan Dying) and was widely and impressively varied in his interests. I couldn’t help but admire his seriousness and industry, and from time to time I’d give him another try, never to any avail. His prose style in fiction struck me as unpleasingly gray and thick, his essays and reviews as fluent but essentially conventional. The only book of his I really liked was Bech: A Book, and I didn’t like it well enough to hang onto my copy when I pruned my library a few years ago. Yet time and again friends whose taste I trusted assured me that I was wrong about Updike, and insisted that I should try, try again.

In the end I finally gave up, and decided that Updike was one of those undeniably important artists, like Wagner or Dreiser, to whose virtues I would always be deaf. It’s been years since I last read a word of his. Needless to say, I regret his passing, and I have no doubt that the world of letters will be much the poorer for his absence. I only wish I understood why.

* * *

Novelist Thomas Mallon offers an alternative view:

He was deeply interested in sex and God, but more than anything he was interested in working–steadily and prodigiously. The Rabbit books, taken together, are the great American novel of the second half of the twentieth century. Even when he was through with them, he kept writing fiction as if, culturally, it still counted–as if it could still land a writer on the cover of Time….

Read the whole thing here.

The New York Times obituary is here.