In March of 1969 I read a piece in Time called “The American Holmes” that compared Rex Stout, the creator of Nero Wolfe and Archie Goodwin, to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson:

In March of 1969 I read a piece in Time called “The American Holmes” that compared Rex Stout, the creator of Nero Wolfe and Archie Goodwin, to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson:

If there is anybody in detective fiction remotely comparable to England’s Sherlock Holmes, it is Rex Stout’s corpulent genius, Nero Wolfe. Like Holmes, Wolfe is coolly intellectual, fanatically thorough and precise, brilliantly epigrammatic; he is also a crotchety bachelor, gastronome, flower fancier and born actor. There is even a family resemblance between the two, considering Wolfe’s physical likeness to Holmes’ brother Mycroft….

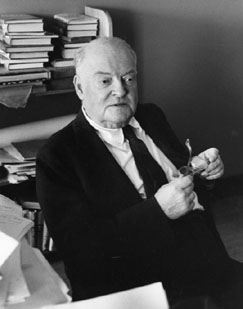

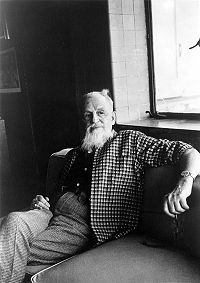

Wolfe’s creator, now an active 82, [is] one of the few detective writers with a wide appeal to the serious fiction reader. Stout serves up lean, lucid prose, masterly narrative construction, intricate yet gimmick-free plotting. To this may be added the flavor of what Ian Fleming called “one of the most civilized minds that has ever been applied to the art of the thriller.”

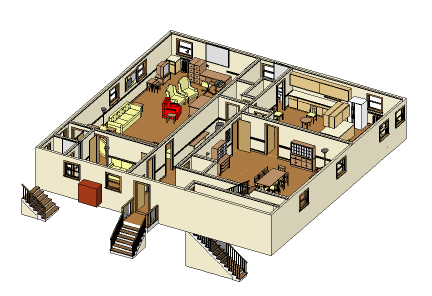

Having subscribed to Time at the tender age of thirteen with the avowed purpose of widening my cultural horizons, I promptly hopped on my bicycle, pedaled to the Smalltown Public Library and checked out a copy of Trio for Blunt Instruments, a collection of three Wolfe novellas originally published in 1964. I picked it because I liked the title, but no sooner did I start reading than I found myself fascinated by the complex relationship between Wolfe, the orchid-growing, woman-hating genius who never left his New York brownstone save under compulsion, and Archie, the wisecracking man of action who did Wolfe’s legwork and served as the narrator of their published adventures in private detection.

No sooner did I finish reading Trio for Blunt Instruments than I went back to check out another Wolfe book. Within a few weeks I’d read everything by Rex Stout that was in the library, so I got my mother to take me to the Book Bug, a used bookstore in Cape Girardeau, a college town not far from Smalltown, where I bought a slightly tattered paperback copy of Gambit. My goal was to collect all of the Nero Wolfe books, which was no easy task in 1969, at least not for a thirteen-year-old boy living in a small Midwestern town. But I kept at it, and my collection was all but complete by the time I graduated from high school in 1974.

Stout died the following year, a few days after the publication of A Family Affair, the forty-sixth and last of the Wolfe books and the first one that I purchased in its original hardcover edition. (I didn’t start buying hardbacks until I was in college.) Having finally read the whole corpus, I started from scratch and read it again. I’ve been doing the same thing at irregular intervals ever since.

In 1944 Edmund Wilson published the first of a widely quoted pair of attacks on the mystery genre in The New Yorker. Rex Stout came in for a fair amount of abuse on that occasion:

In 1944 Edmund Wilson published the first of a widely quoted pair of attacks on the mystery genre in The New Yorker. Rex Stout came in for a fair amount of abuse on that occasion:

It was only when I looked up Sherlock Holmes that I realized how much Nero Wolfe was a dim and distant copy of an original. The old stories of Conan Doyle had a wit and a fairy-tale poetry poetry of hansom cabs, gloomy London Lodgings and lonely country estates that Rex Stout could hardly duplicate with his backgrounds of modern New York; and the surprises were much more entertaining…

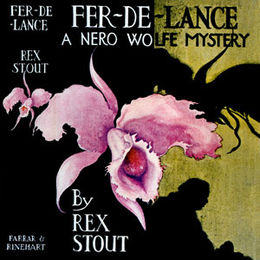

But a great many people of note begged to differ with Wilson, and still do. Stout numbered among his fans such illustrious personages as Somerset Maugham, P.G. Wodehouse, and Kingsley Amis, who called Wolfe “the most interesting of all the great detectives.” In 1934 Justice Holmes, who in his old age developed what he described as an “ignoble liking” for mysteries, read Fer-de-Lance, the first Wolfe novel, and found it to his liking. “This fellow is the best of them all,” he scrawled in the margin of his copy.

For my own part, I’ve never been much drawn to the mystery as a genre, perhaps because I have no interest in the puzzle-based plot mechanisms that drive the “classic” detective story. I no longer return to the Sherlock Holmes stories, and the only mystery novelists whose books I regularly reread for pleasure are Stout, Raymond Chandler, Elmore Leonard, Laura Lippman, and Donald Westlake. (I also enjoy Georges Simenon’s Maigret novels, but for some reason I rarely read them.)

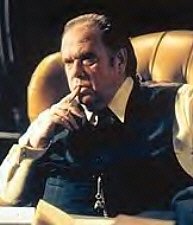

Why do I find these writers so rereadable? Partly because the personalities of their principal characters are so vividly and imaginatively drawn. It was this aspect of Stout’s novels that I had in mind when I wrote a piece for National Review in 2002 about A&E’s regrettably short-lived Nero Wolfe series, which has since been released in its entirety as a boxed set of eight DVDs:

Like all good detective stories, the Nero Wolfe novels are not primarily about their settings, or even their plots. They are conversation pieces, witty studies in human character…less mystery stories than domestic comedies, the continuing saga of two iron-willed codependents engaged in an endless game of oneupmanship. Archie may be Wolfe’s hired hand, but he is also an undefinable combination of servant, goad, court jester, and trusted confidant. His relationship with Wolfe is by definition uneasy, intimate but never affectionate–it’s plain to see that he loves Wolfe like a father, but inconceivable that he would ever admit such a thing–and so the intimacy is transformed into a daily contest for dominance. At least half the fun of the Wolfe books comes from the way in which Stout plays this struggle for laughs.

Alas, my essay on the A&E series inevitably failed to do justice to Stout’s prose style, to which I made only a single passing reference. Describing Wolfe as “a tireless talker endowed with a touch of Johnsonian genius,” I went on to say that it was “no small tribute to Stout’s own brainpower that he was capable of making that characterization plausible.” It’s true enough that Wolfe is a superlative talker. On more than one occasion I’ve quoted him–or, rather, Stout–in an almanac entry. But it is Archie’s narrative voice that drives the books and is the main source of their enduring interest. Jacques Barzun praised Stout for his “sinewy, pellucid, propelling prose,” which seems to me to get it exactly right.

Alas, my essay on the A&E series inevitably failed to do justice to Stout’s prose style, to which I made only a single passing reference. Describing Wolfe as “a tireless talker endowed with a touch of Johnsonian genius,” I went on to say that it was “no small tribute to Stout’s own brainpower that he was capable of making that characterization plausible.” It’s true enough that Wolfe is a superlative talker. On more than one occasion I’ve quoted him–or, rather, Stout–in an almanac entry. But it is Archie’s narrative voice that drives the books and is the main source of their enduring interest. Jacques Barzun praised Stout for his “sinewy, pellucid, propelling prose,” which seems to me to get it exactly right.

Not surprisingly, Stout was at his best when describing his two principal characters. Here is Archie on Wolfe:

It was nothing new for Wolfe to take steps, either on his own, or with one or more of the operatives we used, without burdening my mind with it. His stated reason was that I worked better if I thought it all depended on me. His actual reason was that he loved to have a curtain go up revealing him balancing a live seal on his nose.

And here is Archie on himself:

I would appreciate it if they would call a halt on all their devoted efforts to find a way to abolish war or eliminate disease or run trains with atoms or extend the span of human life to a couple of centuries, and everybody concentrate for a while on how to wake me up in the morning without my resenting it. It may be that a bevy of beautiful maidens in pure silk yellow very sheer gowns, barefooted, singing Oh, What a Beautiful Morning and scattering rose petals over me would do the trick, but I’d have to try it.

I don’t see how anyone with an ear for style can fail to respond to the crispness and verve with which those two paragraphs are charged. It is to revel in such writing that I return time and again to Stout’s books, and in particular to The League of Frightened Men, Some Buried Caesar, The Silent Speaker, Too Many Women, Murder by the Book, Before Midnight, Plot It Yourself, Too Many Clients, The Doorbell Rang, and Death of a Doxy, which are for me the best of all the full-length Wolfe novels.

Just how good are they? When I wrote about Patrick O’Brian in the New York Times Book Review thirteen years ago, I hauled out a very big gun:

One might easily say of [O’Brian’s novels] what F.R. Leavis said of Thomas Peacock: “His books, which are obviously not novels in the same sense as Jane Austen’s, have a permanent life as light reading–indefinitely rereadable–for minds with mature interests.”

But Leavis’s praise, right down to the mention of Austen, embodies an essential distinction, the same one that must be made, however reluctantly, in the case of Patrick O’Brian. Fine as they are, these books are of their kind: brilliant entertainments, rich in implication and almost certainly of permanent interest, yet not quite up to the mark set by Austen and Trollope. They come pretty close, though, and I think that’s the ultimate source, oddly enough, of my nagging dissatisfaction: Mr. O’Brian, like Moses, has seen the promised land, but cannot enter it.

Part of what makes the Nero Wolfe novels so attractive, by contrast, is that one need not draw so high-flown a comparison in order to place them. They are literary entertainments pure and simple, and their author never pretended that they were anything else. Stout knew the difference: he had launched his career by writing a series of modernistic “psychological novels” that attracted little attention, made him little money, and are now completely forgotten. “There are damn few great writers and I’m not one of them,” he told an interviewer in 1941. “While I could afford to I played with words. When I could no longer afford that I wrote for money.”

Part of what makes the Nero Wolfe novels so attractive, by contrast, is that one need not draw so high-flown a comparison in order to place them. They are literary entertainments pure and simple, and their author never pretended that they were anything else. Stout knew the difference: he had launched his career by writing a series of modernistic “psychological novels” that attracted little attention, made him little money, and are now completely forgotten. “There are damn few great writers and I’m not one of them,” he told an interviewer in 1941. “While I could afford to I played with words. When I could no longer afford that I wrote for money.”

That unpretentious confession reminds me of a remark made by the narrator of Evelyn Waugh’s Work Suspended:

There seemed few ways, of which a writer need not be ashamed, by which he could make a decent living. To produce something, saleable in large quantities to the public, which had absolutely nothing of myself in it; to sell something for which the kind of people I liked and respected, would have a use; that was what I sought, and detective stories fulfilled the purpose. They were an art which admitted of classical canons of technique and taste.

Waugh, not at all coincidentally, was an avid reader of mysteries. (He was inexplicably fond of Erle Stanley Gardner’s Perry Mason novels, which I find unreadable.) I like to think that he would have appreciated the Nero Wolfe books had they come to his attention, for they are tasteful, impeccably crafted pieces of writing whose sole purpose is to amuse. They’ve been giving me pleasure for forty years, and I expect them to do so for many more years to come.