I came back to New York long enough to catch the Broadway revival of Richard Greenberg’s The American Plan, then headed west for a pair of California revivals of two plays by John Guare, Six Degrees of Separation in San Diego and Rich and Famous in San Francisco. California is getting the better end of the deal. Here’s an excerpt from today’s Wall Street Journal drama column, in which I review all three shows.

* * *

In 1990 “Six Degrees of Separation” was the play all smart Manhattanites had to see, partly because Stockard Channing was so good in it but mostly because Mr. Guare’s satire of upper-middle-class folkways was so well timed. Money talked very loudly in 1990, and those who didn’t have any longed for a close-up view of the foibles of those who did. Back then I found “Six Degrees” to be clever but shallow, which says far more about me than Mr. Guare. Today it strikes me as one of the strongest American plays of the postwar era, a comedy of liberal manners (and liberal gullibility) whose punch lines are rooted in something more than mere knowingness. In telling the real-life tale of a young black con man (Samuel Stricklen) who wormed his way into a string of Fifth Avenue apartments by passing himself off as Sidney Poitier’s nonexistent son, Mr. Guare tapped into the loneliness and insecurity that have always been part of the American national character. We are all Gatsbys now, his characters told us, and their message rings as true in the Age of Obama as it did in the far-off days of Bush the Elder.

Nowadays “Six Degrees” doesn’t get done as often as it should, presumably because it calls for a cast of 15 and an expensive-looking set. Not only has San Diego’s Old Globe Theatre pulled both commodities out of its institutional hat, but Trip Cullman, the director, has brought off the coup of casting Karen Ziemba in the role that made Ms. Channing a stage star. Ms. Ziemba won a well-deserved Tony for “Contact,” but in recent years she’s been relegated to second-banana status on Broadway, and this is the first time that I’ve seen her in a straight play. It was worth the wait: Ms. Ziemba plays Ouisa, the anxious socialite of “Six Degrees,” with an open-hearted warmth that puts a fresh and convincing spin on Mr. Guare’s script…

Nowadays “Six Degrees” doesn’t get done as often as it should, presumably because it calls for a cast of 15 and an expensive-looking set. Not only has San Diego’s Old Globe Theatre pulled both commodities out of its institutional hat, but Trip Cullman, the director, has brought off the coup of casting Karen Ziemba in the role that made Ms. Channing a stage star. Ms. Ziemba won a well-deserved Tony for “Contact,” but in recent years she’s been relegated to second-banana status on Broadway, and this is the first time that I’ve seen her in a straight play. It was worth the wait: Ms. Ziemba plays Ouisa, the anxious socialite of “Six Degrees,” with an open-hearted warmth that puts a fresh and convincing spin on Mr. Guare’s script…

Though Mr. Guare’s brand of comedy often runs to the zany, he never forgets to make you feel. “Rich and Famous,” now playing at the American Conservatory Theater, is a maniacally funny portrait of Bing Ringling (Brooks Ashmanskas), an unknown playwright who longs in vain to hit the jackpot. Unlike the tightly woven “Six Degrees,” “Rich and Famous,” which dates from 1976, adds up to a series of sketches, one of which contains a brutal skewering of Leonard Bernstein (Stephen DeRosa), with whom Mr. Guare worked in his youth. Yet its specific emotional gravity is surprisingly high, and the overall effect is less farcical than melancholy, especially in the poignant scene in which Bing, Mr. Guare’s maladroit alter ego, runs into an ex-girlfriend (Mary Birdsong) and finds that his failure looks like success from her suburban point of view….

Richard Greenberg is back on Broadway yet again, this time with a revival of “The American Plan,” the 1990 play that put him on the map. It is, like all his other plays, repellently glib, and seeing it in tandem with “Six Degrees of Separation” also suggests that it is…oh, let’s be nice and call it derivative. Like “Six Degrees,” “The American Plan” is a snapshot of upper-middle-class life that hinges on the deceptions of a presentable young man who turns out to be (A) poor and (B) gay. In “The American Plan,” the young man in question (Kieran Campion) is courting a rich girl (Lily Rabe) who is brainy but neurotic, and the air becomes clotted with pseudo-witty one-liners….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Archives for January 2009

TT: Almanac

“Being a playwright is like being a Secret Service man. It’s not something you wrote; it’s somebody whose security you’re in charge of. And you’re always waiting to see where the sniper is going to come from.”

John Guare (quoted in the San Diego Union-Tribune, Jan. 8, 2009)

TT: So you want to see a show?

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

Warning: Broadway shows marked with an asterisk were sold out, or nearly so, last week.

BROADWAY:

• Alfred Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps (comedy, G, suitable for bright children, reviewed here)

• August: Osage County (drama, R, adult subject matter, reviewed here)

• Avenue Q * (musical, R, adult subject matter and one show-stopping scene of puppet-on-puppet sex, reviewed here)

• The Little Mermaid * (musical, G, entirely suitable for children, reviewed here)

• South Pacific * (musical, G/PG-13, some sexual content, brilliantly staged but unsuitable for viewers acutely allergic to preachiness, reviewed here)

OFF BROADWAY:

• The Cherry Orchard (elegiac comedy, G, not suitable for children or immature adults, closes Mar. 8, reviewed here)

• The Cripple of Inishmaan (black comedy, PG-13, closes Mar. 1, reviewed here)

• Enter Laughing (musical, PG-13, closes Mar. 8, reviewed here)

• The Fantasticks (musical, G, suitable for children capable of enjoying a love story, reviewed here)

IN CHICAGO:

• The Seafarer (drama, PG-13, closes Feb. 22, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON ON BROADWAY:

• Equus (drama, R, nudity and adult subject matter, closes Feb. 8, reviewed here)

CLOSING NEXT WEEK IN FORT MYERS, FLA.:

• Dancing at Lughnasa (drama, PG-13, closes Feb. 1, reviewed here)

CLOSING NEXT WEEK IN WEST PALM BEACH, FLA.:

• The Chairs (surrealist comedy, PG-13, far too complicated for children, closes Feb. 1, reviewed here)

CLOSING SUNDAY IN CORAL GABLES, FLA.:

• Adding Machine (serious musical, PG-13, closes Jan. 25, reviewed here)

TT: Almanac

“San Francisco is a mad city–inhabited for the most part by perfectly insane people whose women are of a remarkable beauty.”

Rudyard Kipling, American Notes

TT: Coast to coast to coast (IV)

JANUARY 11 Mrs. T and I reluctantly parted company at the Miami airport, she to spend a few days at a yoga retreat in the Bahamas and I to return to New York City for a week. My first order of business was to do my laundry and speak at Dick Sudhalter’s memorial concert and a retirement dinner for Neal Kozodoy, the outgoing editor of Commentary, where I shared a podium with Bill Bennett, David Brooks, Bill Kristol, and Norman Podhoretz. (Do not adjust your set!) These two events took place simultaneously in different locations, but I managed to get from one to the other and deliver both speeches without bruising myself too badly.

John Podhoretz, who is replacing Neal at Commentary, used the occasion to announce that as of next month’s issue, I will cease to be the magazine’s music critic, a post I’ve held since 1995, and become its chief culture critic, a title that was created by John especially for me. I’ll continue to write about music from time to time as part of my revised portfolio, but my first three pieces under the new dispensation will be about Alfred Hitchcock, Flannery O’Connor, and William Inge. That ought to keep everyone guessing!

John Podhoretz, who is replacing Neal at Commentary, used the occasion to announce that as of next month’s issue, I will cease to be the magazine’s music critic, a post I’ve held since 1995, and become its chief culture critic, a title that was created by John especially for me. I’ll continue to write about music from time to time as part of my revised portfolio, but my first three pieces under the new dispensation will be about Alfred Hitchcock, Flannery O’Connor, and William Inge. That ought to keep everyone guessing!

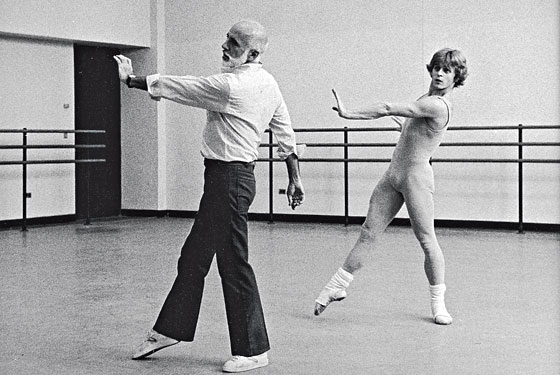

JANUARY 16 I spent the rest of my week in New York seeing plays by Anton Chekhov and Richard Greenberg, writing three Wall Street Journal columns, sifting through my accumulated snail mail, tinkering with Pops: The Life of Louis Armstrong, and attending a screening of Something to Dance About, the upcoming PBS documentary on Jerome Robbins.

Watching the Robbins documentary proved to be an intensely nostalgic experience for me, much more so than I’d expected. The beginning of my involvement in ballet dates from the final years of Robbins’ life. The first piece I ever wrote about dance was an essay about Jerome Robbins’ Broadway that appeared in The New Dance Review in 1990. Eight years later I wrote his obituary for Time. In between I covered the premieres of his last few ballets for the New York Daily News, one of which, A Suite of Dances, figures prominently in Something to Dance About. Of late, though, I’ve drifted away from the world of ballet, and the last dance performance of any consequence that I attended in Manhattan, Kyra Nichols’ farewell, took place in June of 2007.

Watching the Robbins documentary proved to be an intensely nostalgic experience for me, much more so than I’d expected. The beginning of my involvement in ballet dates from the final years of Robbins’ life. The first piece I ever wrote about dance was an essay about Jerome Robbins’ Broadway that appeared in The New Dance Review in 1990. Eight years later I wrote his obituary for Time. In between I covered the premieres of his last few ballets for the New York Daily News, one of which, A Suite of Dances, figures prominently in Something to Dance About. Of late, though, I’ve drifted away from the world of ballet, and the last dance performance of any consequence that I attended in Manhattan, Kyra Nichols’ farewell, took place in June of 2007.

It felt strange to find myself in a roomful of balletomanes for the first time in a year and a half, and stranger still to see Robbins up on the screen, looking just the way he did when I sat three seats away from him at the premiere of New York City Ballet’s revival of Les Noces in 1998. As I wrote in Time two months later:

The once vital choreographer had grown frail, but his snow-white beard still glowed like a beacon, and when the dance was over, he made his careful way to center stage, hobbled by age and illness but radiating undimmed authority. More than a few onlookers wept, knowing that the golden age of ballet–the starlit century of Serge Diaghilev, George Balanchine, Antony Tudor, Sir Frederick Ashton and Jerome Robbins–was drawing at last to a close.

All at once I remembered the inscription on a refrigerator magnet owned by a friend of mine: “Time Flies, Whether You’re Having Fun or Not.”

JANUARY 17 Lunch with Brooke Campbell, a singer-songwriter in whose music I took an interest last year. (She has a new CD out called Sugar Spoon.) She turned out to be a soft-spoken, slightly shy young woman with a North Carolina accent that reminded me of home. The two of us passed a pleasant hour trading musical notes (we both like Aimee Mann, Nickel Creek, and Jonatha Brooke). She played me a song by Rachel Taylor, whose latest CD I ordered as soon as I got home, and I in turn suggested that she check out Erin McKeown.

JANUARY 17 Lunch with Brooke Campbell, a singer-songwriter in whose music I took an interest last year. (She has a new CD out called Sugar Spoon.) She turned out to be a soft-spoken, slightly shy young woman with a North Carolina accent that reminded me of home. The two of us passed a pleasant hour trading musical notes (we both like Aimee Mann, Nickel Creek, and Jonatha Brooke). She played me a song by Rachel Taylor, whose latest CD I ordered as soon as I got home, and I in turn suggested that she check out Erin McKeown.

Brooke’s guitar playing is so harmonically rich and resourceful that I took it for granted that she had musical training. Very much to my surprise, she told me that she’d started playing guitar and writing songs at the age of twenty-one, having previously done nothing more challenging than sing in a church choir. This reminded me of the Mutant, my jazz-singing friend who decided one fine day to take up painting and a month later produced a canvas that reminded me of Hans Hofmann (it hangs over my bookshelves).

Repeat after me: life is unfair.

(To be continued)

TT: Snapshot

The opening sequence from The Killers, Robert Siodmak’s 1946 film version of Ernest Hemingway’s short story, with William Conrad and Charles McGraw. The score is by Miklós Rózsa:

(This is the latest in a weekly series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Wednesday.)

TT: Almanac

“Poor Faulkner. Does he really think big emotions come from big words? He thinks I don’t know the ten-dollar words. I know them all right. But there are older and simpler and better words, and those are the ones I use.”

Ernest Hemingway (quoted in A.E. Hotchner, Papa Hemingway)

TT: Art for politics’ sake

I was eating breakfast in a shabby Latino-friendly diner on San Francisco’s Geary Street when the torch was passed to a new generation–and a new class. It may say something of interest about Barack Obama that I was the only person in the Olympic Flame Diner who was paying any attention to his inauguration, even though the TV over the grill was tuned to CNN. President Obama, on the other hand, has been embraced with wild fervor by America’s educated middle class, including virtually all of our artists. Hence it was of special interest to me that a piece of classical music and a poem were unveiled at the inaugural ceremonies–and that neither was any good at all.

The music was by John Williams, who has his moments (I love Star Wars) but isn’t exactly a serious composer. Not surprisingly, his piece, Air and Simple Gifts, was an exercise in Americana à la Hollywood:

It was noteworthy solely because Williams borrowed so unabashedly from Aaron Copland’s famous setting of the Shaker hymn on which Appalachian Spring is based. (That’s what Itzhak Perlman and Yo-Yo Ma should have played.)

The poem, “Praise Song for the Day,” was by Elizabeth Alexander, a professor at Yale, and it was…well, about what you’d expect from a professor at Yale.

Robert Frost wrote a poem for John Kennedy’s inauguration, though he was unable to read it because of the bright sunlight (he recited “The Gift Outright” from memory instead). The best-remembered lines are the closing couplet, in which Frost foretold the coming of a golden age of poetry and power/Of which this noonday’s the beginning hour. I find the first three lines more touching, though: Summoning artists to participate/In the august occasions of the state/Seems something artists ought to celebrate. Indeed it does, which is why I’m glad that President Obama summoned artists to participate in his inauguration. Still, I can’t help but wish that he’d gone somewhere other than Hollywood and the groves of academe to look for them.

Robert Frost wrote a poem for John Kennedy’s inauguration, though he was unable to read it because of the bright sunlight (he recited “The Gift Outright” from memory instead). The best-remembered lines are the closing couplet, in which Frost foretold the coming of a golden age of poetry and power/Of which this noonday’s the beginning hour. I find the first three lines more touching, though: Summoning artists to participate/In the august occasions of the state/Seems something artists ought to celebrate. Indeed it does, which is why I’m glad that President Obama summoned artists to participate in his inauguration. Still, I can’t help but wish that he’d gone somewhere other than Hollywood and the groves of academe to look for them.

* * *

Here is the complete text of “Dedication,” written by Robert Frost in commemoration of President Kennedy’s 1961 inauguration.