“Provincialism is not merely lacking city taste in arts and manners; it is also an increasingly vital antidote to all would-be central tyrannies.”

John Fowles, introduction to G.B. Edwards, The Book of Ebenezer Le Page

Archives for 2008

TT: Semicolonoscopy

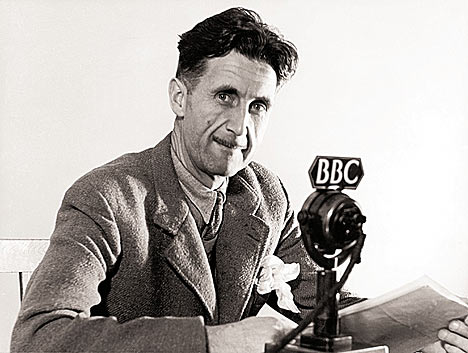

I read Paul Collins’ article in Slate about the decline and fall of the semicolon with interest and amusement. I confess, though, that the first thing I did was search through the piece for George Orwell’s name. While Orwell was mentioned in passing, Collins failed to include the wonderfully trivial fact that the author of Nineteen Eighty-Four claimed to have written an entire novel, Coming Up for Air, that contains no semicolons whatsoever. “I had decided about this time that the semicolon is an unnecessary stop and that I would write my next book without one,” he explained in a letter to Roger Senhouse.

But did he succeed? It’s been years since I last read Coming Up for Air, and I didn’t collate it for semicolons on that occasion. Since then a searchable e-text of the book, which was published in 1939, has been posted by Project Gutenberg, and no sooner did I start trolling for the allegedly superfluous punctuation mark than I found this characteristic passage, in which Orwell’s narrator describes a nasty little diner to which he paid a visit in search of an edible meal:

Behind the bright red counter a girl in a tall white cap was fiddling with an ice-box, and somewhere at the back a radio was playing, plonk-tiddle-tiddle-plonk, a kind of tinny sound. Why the hell am I coming here? I thought to myself as I went in.There’s a kind of atmosphere about these places that gets me down. Everything slick and shiny and streamlined; mirrors, enamel, and chromium plate whichever direction you look in. Everything spent on the decorations and nothing on the food. No real food at all. Just lists of stuff with American names, sort of phantom stuff that you can’t taste and can hardly believe in the existence of. Everything comes out of a carton or a tin, or it’s hauled out of a refrigerator or squirted out of a tap or squeezed out of a tube. No comfort, no privacy. Tall stools to sit on, a kind of narrow ledge to eat off, mirrors all round you. A sort of propaganda floating round, mixed up with the noise of the radio, to the effect that food doesn’t matter, comfort doesn’t matter, nothing matters except slickness and shininess and streamlining. Everything’s streamlined nowadays, even the bullet Hitler’s keeping for you. I ordered a large coffee and a couple of frankfurters. The girl in the white cap jerked them at me with about as much interest as you’d throw ants’ eggs to a goldfish.

Damn.

Having found that a cherished literary myth was nothing more than that, I searched the rest of Coming Up for Air and located four more semicolons. I was shocked–shocked! Maybe Louis Menand was right after all.

Having found that a cherished literary myth was nothing more than that, I searched the rest of Coming Up for Air and located four more semicolons. I was shocked–shocked! Maybe Louis Menand was right after all.

As for me, I rarely use semicolons in my own writing. This is not a quirk: I’ve spent years cultivating the art of writing the way I talk, and you can’t really “speak” a semicolon out loud. (Maybe John Gielgud could, but I can’t.) So I eschew them–usually. I can’t remember the last time I used one in a Wall Street Journal column. The manuscript of Rhythm Man: A Life of Louis Armstrong, which is 175,000 words long, contains no more than one or, at most, two semicolons per chapter, not counting those that appear in quotations from other writers. Several chapters are entirely semicolon-free.

For what it’s worth, here’s an example of how I used the semicolon in Rhythm Man:

For all his virtuosity, Armstrong was never at his best when playing at fast tempos. It was in ballads, swinging medium-tempo numbers, and the blues that he did his most creative improvising. If he had recorded nothing but “Star Dust” and “St. Louis Blues,” he would still be remembered as the greatest jazz soloist of his time; if he had recorded nothing but “Chinatown, My Chinatown” and “I Got Rhythm,” he would be remembered only as a high-note specialist with a funny voice.

And yes, you can say that one out loud. Try it.

TT: Almanac

“Tabitha went to Church with the Priaulx and to Service with my mother sometimes; but I am not sure she had a religion really. She had faith. I don’t know in what, or how. She suffered in her life, yet I doubt if she was ever truly unhappy. She seemed to know that underneath everything was good. I wish I could think the same.”

G.B. Edwards, The Book of Ebenezer Le Page

TT: Hipper than thou

Carrie’s posting about the fifteenth-anniversary reissue of Exile in Guyville reminds me that it was Our Girl who introduced me to the music of Liz Phair twelve years ago. I had come to Chicago to pay her a visit, and she played me a mixtape (remember those?) as we drove to dinner. Our Girl has long considered it her duty to keep me conversant with the newest wrinkles in popular culture, so none of the artists on the tape was familiar to me. The music washed undistractingly over us as we discussed the day’s adventures. Then a woman with a low, throaty voice sang a song whose first lines caught my ear:

Carrie’s posting about the fifteenth-anniversary reissue of Exile in Guyville reminds me that it was Our Girl who introduced me to the music of Liz Phair twelve years ago. I had come to Chicago to pay her a visit, and she played me a mixtape (remember those?) as we drove to dinner. Our Girl has long considered it her duty to keep me conversant with the newest wrinkles in popular culture, so none of the artists on the tape was familiar to me. The music washed undistractingly over us as we discussed the day’s adventures. Then a woman with a low, throaty voice sang a song whose first lines caught my ear:

I woke up alarmed

I didn’t know where I was at first

Just that I woke up in your arms

And almost immediately I felt sorry

“Who’s that?” I asked. The song, OGIC replied, was from an album by a Chicago singer-songwriter that was intended as an “answer” to the Rolling Stones’ Exile on Main Street. “I want to hear the whole thing,” I replied, and later that night I listened to Exile in Guyville for the first time. It opened with another line that made me sit up and take notice: I bet you fall in bed too easily/With the beautiful girls who are shyly brave. The rest of the album hit me just as hard. Not only did I feel that I’d been given a glimpse into the private lives of my younger friends, but I was excited by the spare, raw-sounding instrumental tracks laid down by Phair’s band.

I bought Guyville and Go West, Phair’s second album, as soon as I got back to New York, and told everyone I met about my latest discovery. Most of them were way ahead of me. “You can stop trying to be hip now,” a twentysomething friend said to me with dry, tolerant amusement a few weeks later. “It isn’t working.” I winced at her remark, which reminded me of a scene in Kingsley Amis’ Girl, 20 in which Sir Roy Vandervane, a Leonard Bernstein-like conductor of a certain age who takes up with a seventeen-year-old girl and writes a concerto for violin and rock band, is accused of trying to “arse-creep youth.”

I bought Guyville and Go West, Phair’s second album, as soon as I got back to New York, and told everyone I met about my latest discovery. Most of them were way ahead of me. “You can stop trying to be hip now,” a twentysomething friend said to me with dry, tolerant amusement a few weeks later. “It isn’t working.” I winced at her remark, which reminded me of a scene in Kingsley Amis’ Girl, 20 in which Sir Roy Vandervane, a Leonard Bernstein-like conductor of a certain age who takes up with a seventeen-year-old girl and writes a concerto for violin and rock band, is accused of trying to “arse-creep youth.”

Since then I’ve weathered a midlife crisis, survived a bout of congestive heart failure, and managed to cross the fiftieth meridian without buying a red sports car or marrying a woman half my age. (Mrs. T and I are coeval.) Not surprisingly, I now put less energy into staying abreast of current cultural events. As I wrote in this space two years ago:

I suspect I’ve entered a fallow period, a necessary time of recovery after the frenzied events of the second half of 2005. I nearly died, then I turned fifty: that’s enough to knock anybody off his pins, and I’d say I was well and truly knocked. The other day I had occasion to quote to a friend the Spanish proverb that figures frequently in Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey-Maturin novels, May no new thing arise. That’s for me. More than a few new things arose in my life in the past couple of years, and for the moment I’ve had enough.

This, too, shall pass, sooner or later. At some point I’m sure I’ll start to feel the tug of the new, bob to the surface, and start sniffing the air. I always have. But not just yet. I’m not quite ready to engage with the moment. I think I’ll stick to the tried and true for a little while longer. The world will have to take care of itself, for now.

I’m sniffing the air again, but not so obsessively as I used to: I’ve pretty much given up on new movies, for instance, and I don’t even pretend to know what’s going on in pop music. One can only absorb so many new things in a lifetime. These days I devote most of my absorptive capacity to the shows I write about each Friday in The Wall Street Journal. I’m embarrassed to say that I didn’t even bother to check out Liz Phair’s last album.

Last month Mark Sarvas posted a list of “beloved books he’s afraid to re-read for fear they won’t hold up.” I was tempted to follow suit, but after reading Carrie’s posting, I’m more inclined to opt for music over literature. Perhaps Exile in Guyville belongs on that list. It’s been a couple of years since I last put it on, and I wonder what I’d think of it now. Would it excite me as much as it did when I first heard it in Our Girl’s living room? I’m not entirely sure I want to know. Certain pleasures are better remembered than revisited.

I should add, however, that a fifty-two-year-old man probably has no business feeling nostalgic about something that happened when he was forty. Nostalgia is a seductive and dangerous drug, to be used in the strictest of moderation on pain of losing your grip on the present moment. I don’t often have occasion to quote Frank Zappa, but he once said something very much to the point: “It isn’t necessary to imagine the world ending in fire or ice–there are two other possibilities: one is paperwork, and the other is nostalgia.”

TT: Almanac

“It’s funny how when you remember you can’t choose what it is you remember.”

G.B. Edwards, The Book of Ebenezer Le Page

TT: Refreshment

Look to the right and you’ll find (at last!) a fair amount of new content in the “Top Five” and “Out of the Past” modules of the right-hand column, with still more on the way.

Enjoy.

BOOK

Erin Hogan, Spiral Jetta: A Road Trip through the Land Art of the American West (University of Chicago, $20). A city-dwelling, solitude-hating connoisseur of modern art hops in her compact car, drives west in search of Robert Smithson’s “Spiral Jetty” and a half-dozen other pieces of monumental land art, and finds…herself. Even if (like me) you don’t have any use for minimalism, you’ll be charmed by Hogan’s wryly self-deprecating account of her desert pilgrimage, in the course of which she learned that being alone isn’t so bad after all (TT).

DANCE

Pilobolus (Joyce Theater, 175 Eighth Ave., June 30-July 26). Summer is here, meaning that Pilobolus Dance Theatre has set up shop in Chelsea for its annual month-long summer season of modern dance, gymnastics, head-twisting trompe-l’oeil effects, and (mostly) comic surrealism. Three mixed bills, one of which pairs Day Two, the company’s signature piece, with a new work designed by master puppeteer Basil Twist (TT).