It’s too hot and I’m too busy.

Later.

Archives for 2008

TT: Almanac

“How much time, approximately, can a worker in a hectic, speeded-up world give to his work and be a sane, all-round, informed, and recreated citizen?”

Mary Barnett Gilson, What’s Past Is Prologue

CAAF: Morning coffee*

• Maud finds the online annotated Moby Dick. Suitable for reading on your iPhone during passive commutes then rising exalted to peer over your fellow subway passengers.

• Not a fresh link but of interest if, like me, you’re a fan of Sarah Hall’s Daughters of the North: Galleycat’s interview with Hall where she discusses the novel’s start as a short story.

* Still a cruel reminder of what once was. But I will not surrender to “morning green tea.”

CAAF: John Keats, John Keats, John, please put your scarf on

Is it just me, or is John Keats everywhere right now? In her excellent Believer essay on novel-writing, Zadie Smith talks about her early identification with the poet and the influence of his example:

I was about fourteen when I heard John Keats in there, and in my mind I formed a bond with him, a bond based on class–though how archaic that must sound, here in America. I knew he wasn’t working-class, exactly, and of course he wasn’t black–but in rough outline his situation felt closer to mine than the other writers I’d come across. He felt none of the entitlement of, say, Virginia Woolf, or Byron, or Pope, or Evelyn Waugh. That was very important to me–I think you may have to be English to understand how important. To me, Keats offered the possibility of entering writing from a side door, the one marked Apprentices Welcome Here. Keats went abut his work just like an apprentice: he took a kind of M.F.A. of the mind, albeit alone, and for free, in his little house in Hampstead. A suburban, lower-middle-class boy, a few steps removed from the literary scene, he made his own scene out of the books of his library. He never feared influence–he devoured influences. He wanted to learn from them, even at the risk of their voices swamping his own. And the feeling of apprenticeship never left him: you see it in his early experiments in poetic from, in the letters he wrote to friends expressing his fledgling literary ideas; it’s there, famously, in his reading of Chapman’s Homer, and the fear that he might cease to be before his pen had gleaned his teeming brain. When I’m writing, especially during those horrible first hundred pages, I often think of Keats. The term “role model” is so odious, but the truth is it’s a very strong writer indeed who gets by without a mode kept somewhere in mind. So I think of Keats. Keats slogging away, devouring books, plagiarizing, impersonating, adapting, struggling growing, writing many poems that made him blush, and then a few that made him proud, learning everything he could from whomever he could find, dead or alive, who might have something useful to teach him.

Also stoking the current Keats-biquity is the publication of Posthumous Keats, which Adam Kirsch reviewed in the New Yorker and which I’m reading right now and adore (so I’m not so much being shadowed by the poet as carrying him around in my purse).

TT: Almanac

“There is an enthusiastic reflection that is of the greatest value if one does not allow oneself to be carried away by it.”

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Maxims and Reflections

TT: Here and there

I just got back to Connecticut from a hectic two-state reviewing trip and am returning to New York on Tuesday for a few frenzied days of work. I haven’t had time to blog, but I’ll try to post an update on my recent activities tomorrow, or maybe Wednesday.

Till then.

TT: Almanac

“Well, you could be serious and still have fun. In fact, he believed it was the secret of a happy life, if anybody wanted to know a secret.”

Elmore Leonard, LaBrava

TT: Happiness on the Hudson

Most of today’s Wall Street Journal drama column is devoted to a report on the Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival‘s productions of Cymbeline and Twelfth Night, followed by a few testy remarks about Lincoln Center Festival’s presentation of The Bacchae. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

What makes a festival festive? To answer this question, hop in your car and head for Garrison, the small town across the Hudson River from West Point that is home to my favorite outdoor summer Shakespeare festival. The Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival, founded in 1987, is that rarity of rarities, an artistic enterprise that gets everything right. Impressive as its productions are, the real secret of the festival’s success is that it offers its patrons a total experience that adds up to more than the sum of its admirable parts. The shows are bright and lively, the performers engaging, the setting gorgeous, the atmosphere joyous. I won’t say that it’s impossible to have a bad time at the Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival–some people are inexplicably resistant to pleasure–but I’ve been going to Garrison for four summers now, and my annual visit has become one of the most eagerly awaited dates on my theatrical calendar.

It’s impossible to talk about the festival without first mentioning the site. The company performs in a huge tent pitched on the lawn of the Boscobel House, a lovingly restored Federal-style 1808 mansion located on a bluff overlooking the Hudson River. The performances get underway just as the evening sun slips behind the mountains of the Hudson Highlands. Wise playgoers dine on the lawn an hour or so before curtain time–tasty catered picnic baskets can be ordered in advance–and enjoy a spectacle that has been capturing the imagination of American landscape painters for the better part of two centuries.

It’s impossible to talk about the festival without first mentioning the site. The company performs in a huge tent pitched on the lawn of the Boscobel House, a lovingly restored Federal-style 1808 mansion located on a bluff overlooking the Hudson River. The performances get underway just as the evening sun slips behind the mountains of the Hudson Highlands. Wise playgoers dine on the lawn an hour or so before curtain time–tasty catered picnic baskets can be ordered in advance–and enjoy a spectacle that has been capturing the imagination of American landscape painters for the better part of two centuries.

Sunset on the Hudson can be a hard act to follow, but Hudson Valley pulls it off. The company’s productions are models of uncondescending theatrical populism, reaching out to contemporary audiences without watering down Shakespeare beyond recognition….

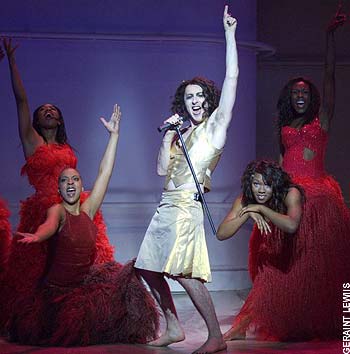

I’ve never found Lincoln Center Festival to be especially festive, though it often presents memorable performances. Part of the problem–maybe most of it–is that the festival takes place in the middle of a bustling, art-crammed city, thus making it difficult to turn off the hum and buzz of urban life and immerse yourself in its wide-ranging fare. Sometimes, though, the fare itself is the problem. This year’s festival, for instance, opened with the National Theatre of Scotland’s tiresomely transgressive production of “The Bacchae,” which struck me as a good working definition of Eurotrash at its trashiest. Picture Alan Cumming in a kilt, being lowered to the stage by his ankles and flashing his buttocks all the way down. Then imagine him as an ultra-campy Dionysus in drag who sashays through a wink-wink-nudge-nudge rewrite of Euripides’ classic Greek tragedy (“Don’t be so coy, big boy”) in which the chorus consists of nine school-of-Motown backup singers decked out in fire-engine red. Get the idea? I did–it took me about 30 seconds–and spent the rest of the night looking at my watch….

I’ve never found Lincoln Center Festival to be especially festive, though it often presents memorable performances. Part of the problem–maybe most of it–is that the festival takes place in the middle of a bustling, art-crammed city, thus making it difficult to turn off the hum and buzz of urban life and immerse yourself in its wide-ranging fare. Sometimes, though, the fare itself is the problem. This year’s festival, for instance, opened with the National Theatre of Scotland’s tiresomely transgressive production of “The Bacchae,” which struck me as a good working definition of Eurotrash at its trashiest. Picture Alan Cumming in a kilt, being lowered to the stage by his ankles and flashing his buttocks all the way down. Then imagine him as an ultra-campy Dionysus in drag who sashays through a wink-wink-nudge-nudge rewrite of Euripides’ classic Greek tragedy (“Don’t be so coy, big boy”) in which the chorus consists of nine school-of-Motown backup singers decked out in fire-engine red. Get the idea? I did–it took me about 30 seconds–and spent the rest of the night looking at my watch….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.