“All men mean well.”

George Bernard Shaw, Man and Superman, “The Revolutionist’s Handbook”

Archives for 2008

TT: Shakespeare on the tube

Mark your calendar: PBS will be telecasting the Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival‘s production of Twelfth Night, together with a backstage documentary called Shakespeare on the Hudson that (according to the press release) “gives viewers an intimate look at the backstory and theatrical process of preparing for and performing Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night to a sell-out crowd. Shakespeare on the Hudson follows the troupe’s core actors through all the real off-stage drama as they prepare for opening night, from the high-pressure auditions and call backs to the final moments backstage before the performance begins.”

Mark your calendar: PBS will be telecasting the Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival‘s production of Twelfth Night, together with a backstage documentary called Shakespeare on the Hudson that (according to the press release) “gives viewers an intimate look at the backstory and theatrical process of preparing for and performing Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night to a sell-out crowd. Shakespeare on the Hudson follows the troupe’s core actors through all the real off-stage drama as they prepare for opening night, from the high-pressure auditions and call backs to the final moments backstage before the performance begins.”

I raved about Hudson Valley’s Twelfth Night in The Wall Street Journal when it opened last month:

The company’s productions are models of uncondescending theatrical populism, reaching out to contemporary audiences without watering down Shakespeare beyond recognition. In John Christian Plummer’s staging of “Twelfth Night,” for instance, the actors all wear dresses of riotously varied kinds, not in order to make a ham-fisted statement about gender politics but to create an atmosphere in which Viola (played by Katie Hartke, who is adorably earnest) can impersonate a handsome boy without stretching credulity until it snaps. While Mr. Plummer and his youthful cast never let you forget that “Twelfth Night” is drop-dead funny–Paul Bates, Richard Ercole, Maia Guest and Wesley Mann are superb clowns all–they are just as careful to give full value to the fresh-faced ardor of Shakespeare’s lovers.

In New York City, Shakespeare on the Hudson and Twelfth Night will air back to back on WNET on September 18 at eight p.m. and on WLIW on September 26 at nine p.m. I don’t know whether or when the two shows will be telecast nationally, so check your local listings–this one is a must.

To watch a video of scenes from Hudson Valley’s Twelfth Night, go here.

TT: Almanac

“Bernard’s humanism was not the less violently held because he had lately begun to doubt whether it was a totally adequate answer.”

Angus Wilson, Hemlock and After

TT: Sacred to the memory

Mrs. T and I spent last Tuesday and Wednesday in Jaffrey, New Hampshire, where we visited the grave of Willa Cather, whom I wrote about in the Teachout Reader and who has been much on my mind lately. Cather was a frequent visitor to Jaffrey–she wrote most of My Ántonia there–and in 1947 she was laid to rest in the Old Burying Ground, a cemetery located in back of the Meeting House, a steeple-topped church-like building that was raised by the citizens of Jaffrey in 1775.

I’m not in the habit of going to the gravesites of famous people, though I did make a point of seeking out H.L. Mencken’s grave when I was writing his biography and, a few years later, stopped by the resting place of Justice Holmes during a visit to Arlington National Cemetery. (I haven’t yet gone to the cemetery in Flushing where Louis Armstrong is buried, but I plan to do so as soon as I get back to New York in September.) This particular pilgrimage, however, seemed right, for the Old Burying Ground is just up the road from the 150-year-old inn where Mrs. T and I were staying, and it also happened that we were in town to see a production of a play whose last act is set in a New Hampshire cemetery.

The Old Burying Ground is shady, quiet, and full of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century tombstones, some worn almost smooth and others as legible as on the day they were carved. A fair number of Revolutionary War veterans are buried there, and their graves are marked with small flags. It’s not a spot that ordinary tourists seek out, nor does Cather’s grave appear to draw many visitors. Her headstone, which is at the southeastern corner of the cemetery, is moderately large, elegantly carved, and bears an inscription from My Ántonia: “…that is happiness; to be dissolved into something complete and great.” Immediately to the right of the stone, which is ringed by bright-colored impatiens, is a small, almost self-consciously discreet plaque that marks the grave of Edith Lewis, Cather’s companion, who outlived her by a quarter-century.

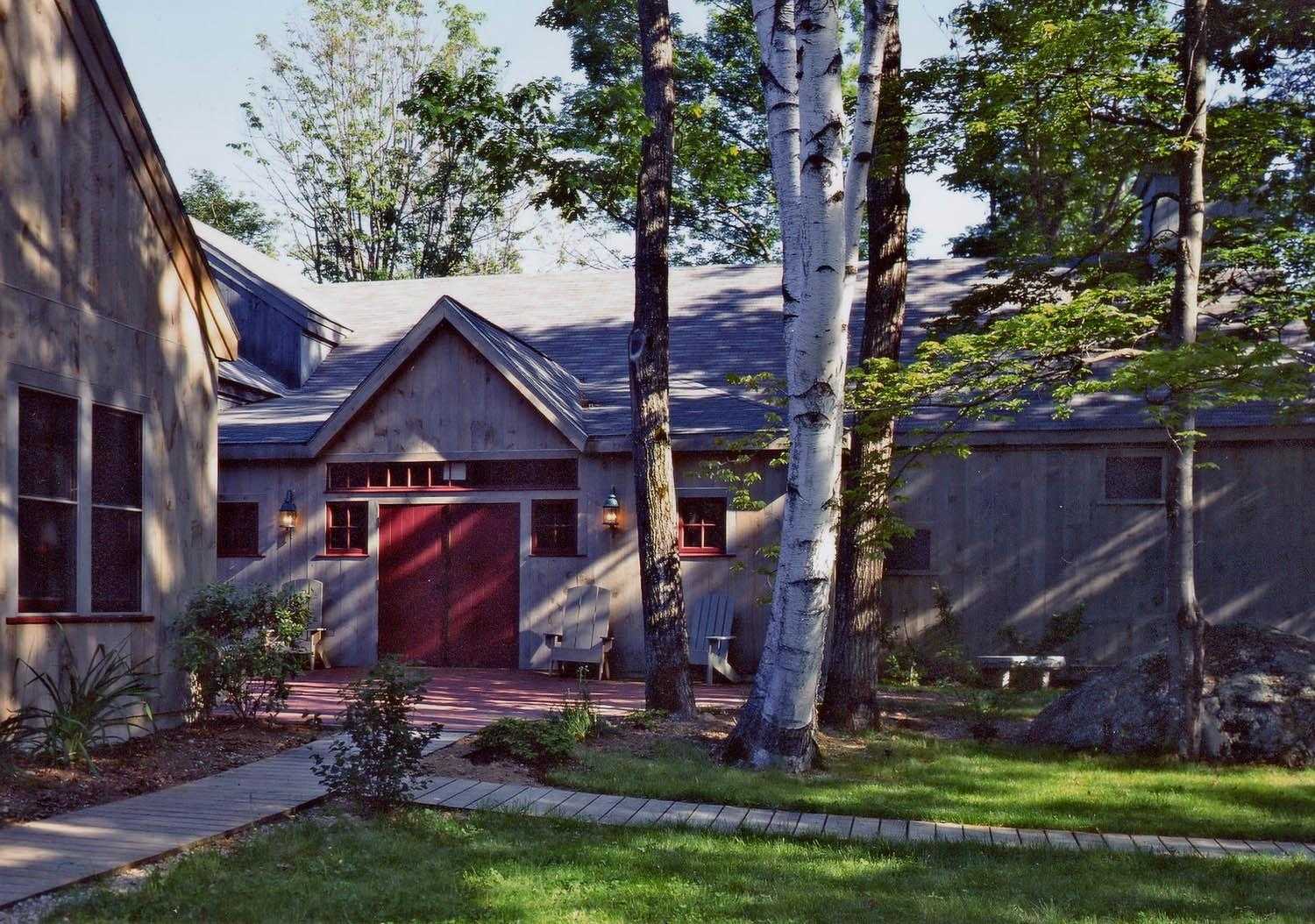

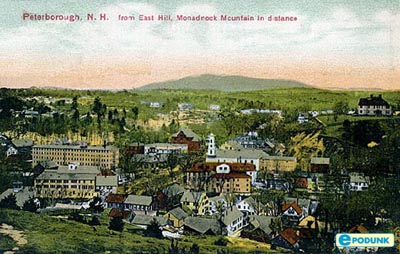

A few hours after departing the Old Burying Ground, Mrs. T and I drove to nearby Peterborough to see the Peterborough Players perform Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, a play that Cather admired greatly. Not long after seeing it on Broadway in 1938, she sent Wilder a letter telling him that Our Town was “the loveliest thing that has been produced in this country in a long, long time–and the truest.” Two years later the Peterborough Players became the first summer theater company ever to perform Our Town, and Wilder himself supervised the staging. He had written much of the play at the MacDowell Colony, which is only a couple of miles away from the converted barn where the Peterborough Players perform, and it is generally thought that he used the small town of Peterborough (pop. 5,883) as a model for Grover’s Corners, the imaginary hamlet (pop. 2,642) in which Our Town is set.

A few hours after departing the Old Burying Ground, Mrs. T and I drove to nearby Peterborough to see the Peterborough Players perform Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, a play that Cather admired greatly. Not long after seeing it on Broadway in 1938, she sent Wilder a letter telling him that Our Town was “the loveliest thing that has been produced in this country in a long, long time–and the truest.” Two years later the Peterborough Players became the first summer theater company ever to perform Our Town, and Wilder himself supervised the staging. He had written much of the play at the MacDowell Colony, which is only a couple of miles away from the converted barn where the Peterborough Players perform, and it is generally thought that he used the small town of Peterborough (pop. 5,883) as a model for Grover’s Corners, the imaginary hamlet (pop. 2,642) in which Our Town is set.

The role of the Stage Manager is being played this summer by James Whitmore, who is eighty-six years old. His age adds a deeper resonance to the lines he speaks at the beginning of the graveyard scene:

You know as well as I do that the dead don’t stay interested in us living people for very long. Gradually, gradually, they lose hold of the earth…and the ambitions they had…and the pleasures they had…and the things they suffered…and the people they loved.

They get weaned away from earth–that’s the way I put it,–weaned away.

As I listened to Whitmore last Wednesday night, I remembered the Old Burying Ground, and the shyly modest plaque tucked alongside the handsome gravestone inscribed with a line from a ninety-year-old novel that continues to be read. What will survive of us is love, I thought, recalling the poem by Philip Larkin that last came to my mind when, two and a half years ago, I turned on a car radio and heard by chance the recorded voice of a friend who had died a decade earlier.

The next morning Mrs. T and I paid a visit to Peterborough’s East Hill Cemetery, an out-of-the-way spot that many well-informed locals believe to be the original of the unnamed cemetery in Our Town, though Wilder himself never admitted as much. So far as I could tell, no one has been buried there since 1932, but the Petersborough Historical Society continues to maintain the grounds and looks after the increasingly fragile headstones. East Hill is steep and there’s nowhere to park, so we left our rented car by the side of the road and started climbing. Within a minute or two we felt as though we’d stepped through a curtain into a lost world, one that Wilder’s Stage Manager describes with haunting precision:

The next morning Mrs. T and I paid a visit to Peterborough’s East Hill Cemetery, an out-of-the-way spot that many well-informed locals believe to be the original of the unnamed cemetery in Our Town, though Wilder himself never admitted as much. So far as I could tell, no one has been buried there since 1932, but the Petersborough Historical Society continues to maintain the grounds and looks after the increasingly fragile headstones. East Hill is steep and there’s nowhere to park, so we left our rented car by the side of the road and started climbing. Within a minute or two we felt as though we’d stepped through a curtain into a lost world, one that Wilder’s Stage Manager describes with haunting precision:

This is certainly an important part of Grover’s Corners. It’s on a hilltop–a windy hilltop–lots of sky, lots of clouds,–often lots of sun and moon and stars….

Yes, beautiful spot up here. Mountain laurel and li-lacks. I often wonder why people like to be buried in Woodlawn and Brooklyn when they might pass the same time up here in New Hampshire.

Over there–

Pointing to stage left

are the old stones,–1670, 1680. Strong-minded people that come a long way to be independent. Summer people walk around there laughing at the funny words on the tombstones…it don’t do any harm. And genealogists come up from Boston–get paid by city people for looking up their ancestors. They want to make sure they’re Daughters of the American Revolution and of the Mayflower…Well, I guess that don’t do any harm, either. Wherever you come near the human race, there’s layers and layers of nonsense….

Yes, an awful lot of sorrow has sort of quieted down up here.

People just wild with grief have brought their relatives up to this hill. We all know how it is…and then time…and sunny days…and rainy days…’n snow…We’re all glad they’re in a beautiful place and we’re coming up here ourselves when our fit’s over.

Those words echoed in my mind’s ear as we walked around the cemetery, pausing from time to time to read the wholly unfunny words on the oddly tilted stones. Prepare for Death and follow me: that’s the last line of the half-legible quatrain carved at the base of the tombstone of Samuel Stinson, who died in 1771 and now reposes on East Hill, surrounded by his family. Might Wilder have had him in mind when he gave a name to Simon Stimson, the drunken, unhappy choirmaster of Our Town?

Mrs. T and I didn’t have much to say as we made our way back down the hill. A light summer shower was falling, just as it does in the last act of Our Town, and we were each lost in our separate thoughts. Once more I recalled the words of the Stage Manager, a role that Thornton Wilder played on several occasions, both in summer-stock productions and on Broadway for two weeks in September of 1938:

There are the stars–doing their old, old crisscross journeys in the sky. Scholars haven’t settled the matter yet, but they seem to think there are no living beings up there. Just chalk…or fire. Only this one is straining away, straining away all the time to make something of itself. The strain’s so bad that every sixteen hours everybody lies down and gets a rest.

He winds his watch.

Hm….Eleven o’clock in Grover’s Corners.–You get a good rest, too. Good night.

For those of us still on earth, straining to make something of ourselves, it seems there is no weaning away from the people we love and lose: they are always there, dissolved into the completeness of eternity, waiting patiently–and, I suspect, indifferently–for the little resurrection that is memory.

TT: Almanac

“I sat down in the middle of the garden, where snakes could scarcely approach unseen, and leaned my back against a warm yellow pumpkin. There were some ground-cherry bushes growing along the furrows, full of fruit. I turned back the papery triangular sheaths that protected the berries and ate a few. All about me giant grasshoppers, twice as big as any I had ever seen, were doing acrobatic feats among the dried vines. The gophers scurried up and down the ploughed ground. There in the sheltered draw-bottom the wind did not blow very hard, but I could hear it singing its humming tune up on the level, and I could see the tall grasses wave. The earth was warm under me, and warm as I crumbled it through my fingers. Queer little red bugs came out and moved in slow squadrons around me. Their backs were polished vermilion, with black spots. I kept as still as I could. Nothing happened. I did not expect anything to happen. I was something that lay under the sun and felt it, like the pumpkins, and I did not want to be anything more. I was entirely happy. Perhaps we feel like that when we die and become a part of something entire, whether it is sun and air, or goodness and knowledge. At any rate, that is happiness; to be dissolved into something complete and great. When it comes to one, it comes as naturally as sleep.”

Willa Cather, My Ántonia

SOUSA THE STORYTELLER

“Now that I’ve read John Philip Sousa’s autobiography, I’m surprised that it isn’t better known to historians of American music. Like Louis Moreau Gottschalk’s Notes of a Pianist before it, Marching Along provides a priceless glimpse of the lost world of music making in Victorian America…”

GALLERY

Diebenkorn in New Mexico (Phillips Collection, 1600 21st St. NW, Washington, D.C., up through Sunday). If you haven’t yet seen this important show of abstract paintings and works on paper, don’t delay–it closes this weekend. Richard Diebenkorn created these works when he lived in Albuquerque from 1950 to 1952, and the best of them suggest with uncanny exactitude the austere yet wrenchingly vivid New Mexico landscape (TT).

TT: Greasepaint under the redwoods

In today’s Wall Street Journal drama column I review three shows, Burn This, All’s Well That Ends Well, and Bach in Leipzig, currently being performed at Shakespeare Santa Cruz, plus an off-Broadway show, the Irish Repertory Theatre’s production of Around the World in 80 Days. I liked them all. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Outdoor theater festivals are like picnics–the food tastes better when eaten al fresco, but sometimes it rains. Shakespeare Santa Cruz, founded in 1981, splits the difference by performing in two different theaters, one outside and the other inside, both of them deep within the woodsy campus of the University of California, Santa Cruz. Each summer the company presents two Shakespeare plays in a natural amphitheatre located in a redwood grove and two modern plays in a nearby 527-seat indoor theater equipped with stadium seating and a thrust stage. I’ve been hearing exciting things about the festival, so I flew out to California last weekend and caught three shows there, all of which were worthy of their sylvan setting.

Lanford Wilson’s “Burn This,” to be sure, no longer looks quite so fresh as it did in the long-ago days when the wisecracking gay second-banana character had yet to become a cliché. Twenty-one years after it transferred to Broadway, “Burn This” can now be seen for what it is, a sentimental variation on “A Streetcar Named Desire” in which the crazy girl is a workaholic choreographer who lives in a converted loft and longs to get a life, the tough-guy stud is a closet aesthete and everybody lives happily ever after. No wonder it ran for 437 performances!

Lanford Wilson’s “Burn This,” to be sure, no longer looks quite so fresh as it did in the long-ago days when the wisecracking gay second-banana character had yet to become a cliché. Twenty-one years after it transferred to Broadway, “Burn This” can now be seen for what it is, a sentimental variation on “A Streetcar Named Desire” in which the crazy girl is a workaholic choreographer who lives in a converted loft and longs to get a life, the tough-guy stud is a closet aesthete and everybody lives happily ever after. No wonder it ran for 437 performances!

On the other hand, Mr. Wilson is a playwright of quality, and if “Burn This” has a core of mush, it’s also well made, well written, very funny when it wants to be and an effective vehicle for four interesting actors and a director who knows how to shift them into overdrive. Shakespeare Santa Cruz delivers the goods…

If you long for theatrical froth whipped up with insolent panache, you’ll have a hard time finding a more satisfying show than the Irish Repertory Theatre’s production of “Around the World in 80 Days,” Mark Brown’s stage version of Jules Verne’s 1873 novel about a stiff-upper-lipped Londoner who uproots himself from the Reform Club to go charging around the globe. Co-produced with Cincinnati Playhouse in the Park, the company that brought you John Doyle’s miniaturized revival of “Company,” “Around the World in 80 Days” is performed on a very, very small stage on which Phileas Fogg (Daniel Stewart) and his trusty servant Passepartout (Evan Zes) circumnavigate the world via steamship, express train and chartered elephant. The cast consists of five actors and two “Foley artists” who supply sound effects and incidental music in full view of the audience….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.