“Beauty, like all other qualities presented to human experience, is relative; and the definition of it becomes unmeaning and useless in proportion to its abstractness. To define beauty not in the most abstract, but in the most concrete terms possible, not to find a universal formula for it, but the formula which expresses most adequately this or that special manifestation of it, is the aim of the true student of aesthetics.”

Walter Pater, Studies in the History of the Renaissance

Archives for 2008

TT: Here be dragons

I’ve been reading Thomas A. Heinz’s Frank Lloyd Wright Field Guide, a book that describes every surviving building designed by Wright, tells you how to get to them, and assigns each one a five-star rating. The Field Guide also includes a brief discussion of the relative accessibility of each building. In most cases it’s a single sentence, usually either “The house can be seen from the street” or “The house cannot be seen from the street.” In certain cases, however, Heinz goes a bit further, and on occasion he really lets himself ago.

Some of his entries speak of bitter disappointment:

• “Visible from street and backyard but little to see” (Charles L. Manson House, Wausau, Wisconsin).

• “The station can be seen at all times and in all conditions. However, there is little to recommend a trip so far north unless visiting Duluth or the Boundary Waters” (Lindholm Service Station, Cloquet, Minnesota).

• “The front of the house is screened by evergreen trees. One can see only glimpses of the building, making photography of the subject frustrating” (Frank J. Baker House, Wilmette, Illinois).

Others hint at acute embarrassment:

• “The house is set well back on the site and cannot be seen from the street. Walking down the drive is not a good idea as it would disturb the occupants” (Carlton D. Wall House, Plymouth, Michigan).

• “The house can only be approached via the long driveway and by the time the house becomes visible one is nearly at the front door” (Duey Wright House, Wausau, Wisconsin).

I bet Mr. Heinz had some ‘splainin’ to do that day.

Like all Wright devotees, Thomas Heinz is a determined and tenacious fellow who will go to considerable trouble to see whatever there is to see:

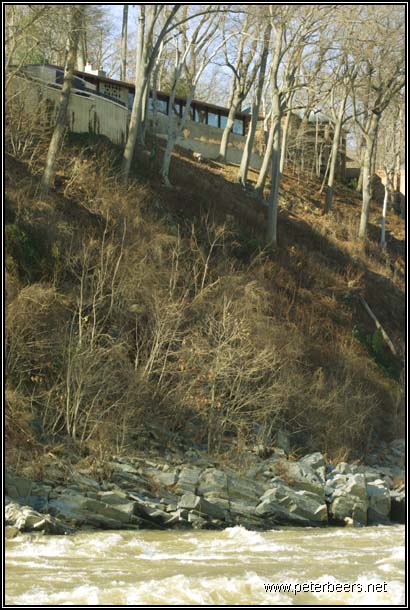

• “The house is over a small hill on the river slope. Only the garage doors can be seen from the roadside. The front of the house can be seen from across the river and the filtration plant. A fence with a gate obscures the house” (Luis Marden House, McLean, Virginia).

• “The house is over a small hill on the river slope. Only the garage doors can be seen from the roadside. The front of the house can be seen from across the river and the filtration plant. A fence with a gate obscures the house” (Luis Marden House, McLean, Virginia).

On occasion, though, he seems to have gotten himself into hot water. Some of the latter entries are devastatingly succinct:

• “Not visible. Beware of the dogs” (Maurice Greenberg House, Dousman, Wisconsin).

Others supply a proliferation of alarming detail:

• “The house is very difficult to see in both summer and winter because of the profusion of small trees and shrubs. There is an electric eye across the driveway that alerts the occupants to anyone approaching the house” (John O. Carr House, Glenview, Illinois).

• “The house is set almost a mile back from the public road, behind several gates and fences, and is extremely difficult to locate. It is still a private home and is not worth pursuing unless invited” (Amy Alpaugh Studio, Northport, Michigan).

• “The house cannot be seen from the street. There are barbed wire fences and dogs for the cattle and the occasional trespasser” (Arnold Friedman House, Pecos, New Mexico).

• “The compound is not accessible because of the narrow private road and ferocious animals kept by the owners. Unless invited, it would be better to avoid this house” (Donald Lovness House and Cottage, Stillwater, Minnesota).

One entry is so rich in implication as to suggest an unwritten short story:

• “The island is approachable only by boat. The island is guarded by dogs and a gate prevents getting past the dock. Only a small portion of the building can be seen from the water. The trained dogs are ever-present and have been known to chase passing boats” (A.K. Chahroudi Cottage, Mahopac, New York).

Here’s my favorite piece of cautionary advice:

• “Only a small portion of the top floor can be seen across the concrete court. The house can be seen from Highway 9 above the waterworks” (Frank Bott House, Kansas City, Missouri).

Talk about nostalgia! I used to go parking in the hills above the Kansas City Waterworks, some thirty-odd years ago. I don’t remember looking for any Frank Lloyd Wright houses, though….

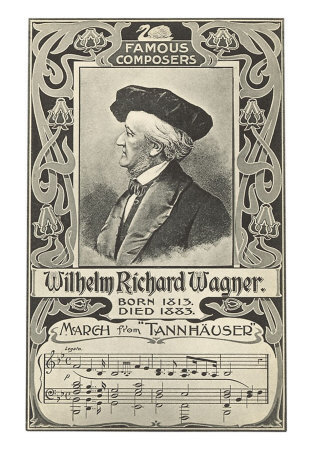

TT: I don’t do Wagner

I’ve returned to New York after a long absence, and it will be a while longer before I’m ready to start blogging regularly again. Aside from everything else, I have a lot of snail mail to open and digest. So while I’m playing catch-up, I’ve decided to post a couple of long-lost pieces of mine that date from the Nineties and have never been reprinted since their original publication in Opera News, for which I used to write once upon a time.

The first one is an essay called “I Don’t Do Wagner” that dates from 1997. In case you’re wondering–and I doubt you are–I haven’t changed my mind since then.

* * *

When Opera News asked me to review performances at the Met. I happily agreed, with a single caveat: “Please don’t ask me to cover Wagner.” And I never have. Nor do I review Wagner performances in the New York Daily News, for which I cover classical music and dance. I got caught a couple of years ago, when the New York Philharmonic opened its season with a Wagner-Strauss bill featuring Jessye Norman–there was no way I could wiggle out of that one–but otherwise, I have yet to write a word for either publication on the heated subject of the Beast of Bayreuth.

When Opera News asked me to review performances at the Met. I happily agreed, with a single caveat: “Please don’t ask me to cover Wagner.” And I never have. Nor do I review Wagner performances in the New York Daily News, for which I cover classical music and dance. I got caught a couple of years ago, when the New York Philharmonic opened its season with a Wagner-Strauss bill featuring Jessye Norman–there was no way I could wiggle out of that one–but otherwise, I have yet to write a word for either publication on the heated subject of the Beast of Bayreuth.

Spare me your angry letters, dear Perfect Wagnerites: one of the advantages of no longer being young is that you’re expected to start making up your mind about certain things. Time was when I pretended to keep an open mind about Richard Wagner–but no more. He is not now and never has been my cup of tea, and I plan, insofar as possible, to go through the remainder of my life without ever attending another public performance of his music. Nor do I see any reason to explain why. You’ve heard it all before, from others if not from me: countless distinguished critics and composers have been staunch anti-Wagnerians, publishing reams of articulate prose about his aesthetic demerits. Instead, I propose to talk about the lifestyle of a Wagner-hater, a subject which, to the best of my knowledge, has yet to be discussed in print.

It seems to me that those of us who don’t do Wagner deserve a certain amount of sympathy. As a passionate devotee of old records, for example, I’m constantly obliged to listen to Wagner in order to savor the singing of such artists as Lauritz Melchior, Friedrich Schorr and Kirsten Flagstad, which is rather like eating the lettuce to get at the dressing. I suppose I could stick to those singers’ recordings of other music, but it really wouldn’t be the same, would it? Aside from the fact that you can only enjoy hearing Grieg’s “Haugtussa” so many times, I can’t deny that Wagner knew better than any other composer how to make a big voice ring and shine.

Conductors pose a similar problem. Arturo Toscanini’s 1946 recording with the NBC Symphony of the Meistersinger Overture figures on my short list of the best recordings of all time, and Wilhelm Furtwängler’s 1938 Parsifal excerpts with the Berlin Philharmonic aren’t far behind. To expel such classic performances from my CD collection simply because I don’t like Wagner would be throwing the bath water out with the baby.

I’d also feel sorely deprived if I couldn’t read about Wagner, whose life and character I find endlessly fascinating. I read Wagner biographies the way good liberals read Nixon biographies, and I suspect I get a lot more pleasure out of Wagner scholarship than the average Wagnerite, precisely because the old boy was so awful: the deeper you dig, the blacker the dirt. I also dote on Wagner parodies, from Bugs Bunny’s “What’s Opera, Doc?” to Emanuel Chabrier’s “Souvenirs de Munich,” a madly funny quadrille for piano duet on themes from Tristan. Chabrier, of course, was an eminent Wagnerian, and a goodly number of other musicians who shared his mistaken views composed music in which the repulsive influence of their idol was miraculously put to good use. Merely because Pelléas et Melisande was profoundly influenced by Wagner is no reason not to like it.

As it happens, I really do like some Wagner: the Siegfried Idyll (especially in Otto Klemperer’s marvelously austere one-player-to-a-part recording), certain orchestral preludes and interludes, the odd vocal excerpt. I can even remember a month-long stretch when I found myself mysteriously drawn to the first act of Die Walküre, though I think this had more to do with the fact that I was listening to the Melchior-Lotte Lehmann-Bruno Walter recording than with the actual merits of the music itself. And there are times when it occurs to me–strictly in theory, you understand–that I might be able to stomach a whole performance of Die Meistersinger.

Still, I’d never actually break down and go. I know I’d be squirming in my seat hours before the final curtain. I am simply not susceptible to the magic spell of which Neville Cardus, the great English music critic, wrote so eloquently in a review of a 1933 Wagner night at Covent Garden: “A music critic’s life is hard when he is compelled, in order to get his work done in time, to leave a performance of Die Walküre at the peak of magnificence. Tonight I found myself in the squalor of Bow Street just after the end of the second act, and the contrast of reality with the splendor of Wagner’s remote world was too great to bear. Still bereft of ordinary senses, I wandered about the maze of Long Acre and Drury Lane until I woke up and discovered myself a mile from where I ought to have been.”

Reading that majestic paragraph, I feel almost capable of peering through the cloudy scrim and understanding what it is that hypnotizes the thousands of hopeless masochists who turn out night after night when the Met is doing the Ring. Almost–but not quite. For I don’t do Wagner, and surely this is no time to start. A newly middle-aged man has his dignity to consider. Aside from everything else, what if liked it? How could I face my friends? And worst of all, where would I find the time to listen to all those damn operas? Life’s too short for Götterdämmerung, especially when you’ve already lived half of yours.

TT: Almanac

“Wagner’s art is the most sensational self-portrayal and self-critique of German nature that it is possible to conceive.”

Thomas Mann, “Suffering and Greatness of Richard Wagner”

CD

Paul Moravec, Cool Fire/Chamber Symphony (Naxos, out Sept. 30). Two new large-scale pieces of chamber music by my Pulitzer Prize-winning operatic collaborator, performed to perfection by a group of instrumentalists from the Bridgehampton Chamber Music Festival and now available for pre-ordering from amazon.com. I wrote the liner notes: “Pure Moravec from first bar to last, full of heart-lifting melodies and enlivened by the proliferating rhythmic energy which propels the light-footed, almost Mendelssohnian scherzi that are to be found in most of Paul’s multi-movement works. Note, too, the ingeniously wrought small-scale instrumentation, whose luminous transparency reminds me at times of Ravel.” Yes, he’s that good (TT).

FILM

Act of Violence. A hard, unrelenting 1949 film noir about a World War II vet (Van Heflin) who made a bad mistake and the crippled ex-friend (Robert Ryan at his tortured best) who means to make him pay for it. Directed with exceptional skill by Fred Zinnemann, this tough tale of postwar angst also features strong supporting performances by Janet Leigh (as Heflin’s innocent young wife) and Mary Astor (as an aging hooker) and a memorable score by Bronislau Kaper. Noir wasn’t MGM’s strong suit, but this film is an exception to the rule (TT).

TT: Changing times

When Hurricane Katrina roared through New Orleans three years ago, OGIC and I temporarily turned this blog into an online clearinghouse for Web-based hurricane-related news and comment. We were–amazingly–the first and only bloggers to think of doing such a thing. Fortunately, the Web and the mainstream media have both changed greatly since 2005, and so I don’t think our services will be needed this time around.

I do, however, want to post a link to Ridin’ Gustav, a blog by an ex-Marine who’s decided to hunker down in New Orleans and ride out the storm instead of joining in the evacuation:

I’d rather be on hand to help with the immediate aftermath if it’s bad. Think of me as an unofficial First Responder. Rather be a sheepdog than a sheep.

So, I figured while I’m here, I might as well post an eyewitness account of the festivities. I’ve got still and video cameras, and will post what I can for as long as the power, and then my UPS, holds out.

I plan to keep an eye on this blog in the next few days. So should you.

TT: The two faces of Henry Higgins

The dogs bark, the caravan moves on. A week after I wrapped up my furious circuit of New England summer theater festivals, today’s Wall Street Journal drama column is devoted to the last of my reports on the shows I saw, the Ogunquit Playhouse’s My Fair Lady in Maine and Goodspeed Musicals’ Half a Sixpence, both of which delighted me. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Could it be that “My Fair Lady” is a better work of art than “Pygmalion”? Heresy! Heresy! Yet such things, after all, do happen. Many theatergoers, myself among them, believe that “Falstaff,” Verdi’s last opera, is a distinct improvement on Shakespeare’s “The Merry Wives of Windsor,” and the musical that Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe adapted in 1956 from George Bernard Shaw’s 1913 play is at the very least better loved than its source, containing as it does such gilt-edged standards as “Get Me to the Church on Time,” “I Could Have Danced All Night,” “I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face,” “On the Street Where You Live,” “With a Little Bit of Luck” and “Wouldn’t It Be Loverly?” You can’t go wrong with a score that good, and while “Pygmalion” has a satirical edge that is dulled in “My Fair Lady,” Lerner’s book was faithful for the most part to both the spirit and the letter of Shaw’s great play.

Comparisons between the two shows were inevitably encouraged by the Roundabout Theatre Company’s lively 2007 revival of “Pygmalion,” but it’s been a decade and a half since “My Fair Lady” was last seen on Broadway. So when the Ogunquit Playhouse announced that Jefferson Mays, the Henry Higgins of the Roundabout’s “Pygmalion,” would be playing the same role in its revival of “My Fair Lady,” I decided at once to head north to Maine and check out his performance. It turned out to be exceptional, as did the rest of the production. Strongly cast and sharply directed by Shaun Kerrison, who also restaged the road-show version of Trevor Nunn’s West End “My Fair Lady” revival that recently ended a 24-city U.S. tour, this modestly scaled staging is an immensely appealing piece of work that pleased me no end….

Comparisons between the two shows were inevitably encouraged by the Roundabout Theatre Company’s lively 2007 revival of “Pygmalion,” but it’s been a decade and a half since “My Fair Lady” was last seen on Broadway. So when the Ogunquit Playhouse announced that Jefferson Mays, the Henry Higgins of the Roundabout’s “Pygmalion,” would be playing the same role in its revival of “My Fair Lady,” I decided at once to head north to Maine and check out his performance. It turned out to be exceptional, as did the rest of the production. Strongly cast and sharply directed by Shaun Kerrison, who also restaged the road-show version of Trevor Nunn’s West End “My Fair Lady” revival that recently ended a 24-city U.S. tour, this modestly scaled staging is an immensely appealing piece of work that pleased me no end….

Pop quiz: What other musical about class warfare is based on a celebrated piece of Edwardian literature? Answer: “Half a Sixpence,” now being performed to exhilarating effect by Goodspeed Musicals, was adapted by David Heneker and Beverley Cross from “Kipps,” H.G. Wells’ once-popular 1905 novel about a working-class draper’s apprentice who inherits a fortune and is catapulted into the ranks of medium-high society. Needless to say, Cross’ book retains little more than the bare outline of “Kipps,” a 500-page socialist tract disguised as a Dickensian romance in which the author of “The War of the Worlds” railed against “the great stupid machine of retail trade,” but the musical still manages to hint at Wells’ righteous anger, albeit in much-blunted form….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.