“One begins to see, for instance, that painting a picture is like fighting a battle; and trying to paint a picture is, I suppose, like trying to fight a battle. It is, if anything, more exciting than fighting it successfully. But the principle is the same. It is the same kind of problem as unfolding a long, sustained, interlocked argument. It is a proposition which, whether of few or numberless parts, is commanded by a single unity of conception. And we think–though I cannot tell–that painting a great picture must require an intellect on the grand scale. There must be that all-embracing view which presents the beginning and the end, the whole and each part, as one instantaneous impression retentively and untiringly held in mind. When we look at the larger Turners–canvases yards wide and tall–and observe that they are all done in one piece and represent one single second of time, and that every innumerable detail, however small, however distant, however subordinate, is set forth naturally and in its true proportion and relation, without effort, without failure, we must feel in the presence of an intellectual manifestation the equal in quality and intensity of the finest achievements of warlike action, of forensic argument, or of scientific or philosophical adjudication.”

Winston Churchill, Painting as a Pastime (courtesy of Eric Gibson)

Archives for 2008

TT: Almanac (in memoriam)

At once a voice arose among

The bleak twigs overhead

In a full-hearted evensong

Of joy illimited;

An aged thrush, frail, gaunt, and small,

In blast-beruffled plume,

Had chosen thus to fling his soul

Upon the growing gloom.

So little cause for carolings

Of such ecstatic sound

Was written on terrestrial things

Afar or nigh around,

That I could think there trembled through

His happy good-night air

Some blessed Hope, whereof he knew

And I was unaware.

Thomas Hardy, “The Darkling Thrush”

* * *

Dick Sudhalter plays Bix Beiderbecke’s “Davenport Blues” with the New York Jazz Repertory Company at Carnegie Hall in 1975:

TT: Richard M. Sudhalter, R.I.P.

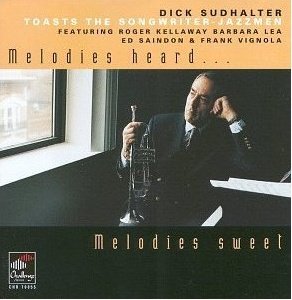

Dick Sudhalter wrote three of the most important books ever published about jazz and American popular music, Bix: Man and Legend, Lost Chords: White Musicians and Their Contribution to Jazz, 1915-1945, and Stardust Melody: The Life and Music of Hoagy Carmichael. He was also a trumpet player of great elegance and distinction who didn’t make nearly as many records as he should have, though Melodies Heard, Melodies Sweet showed him off to the best possible advantage.

Dick Sudhalter wrote three of the most important books ever published about jazz and American popular music, Bix: Man and Legend, Lost Chords: White Musicians and Their Contribution to Jazz, 1915-1945, and Stardust Melody: The Life and Music of Hoagy Carmichael. He was also a trumpet player of great elegance and distinction who didn’t make nearly as many records as he should have, though Melodies Heard, Melodies Sweet showed him off to the best possible advantage.

In private life Dick was as dapper as his playing, and old-fashioned in all the best ways. He liked Chicago-style jazz, British tailoring, black-and-white movies, Marmite, and The New Yorker before Tina Brown got her hands on it. Not surprisingly, he was more than a little bit at odds with much of the modern world, and I suspect that he would have been vastly happier had he been born in 1908 instead of 1938. He was also a pessimist by nature, but like many such folks, he gave more pleasure than he got–and, I suspect, got more pleasure than he usually cared to admit.

Dick and I were close friends, and so it grieved me deeply when his body began to betray him a few years ago. First came a stroke that robbed him of the power to play his horn and left him increasingly slow of speech (though never of mind). Then he fell victim to multiple system atrophy, an appalling disease that in time made it impossible for him to talk at all. That such an ailment should have struck down so brilliantly articulate a man was one of those horrific ironies with which life likes to remind us that it holds the whip hand.

I knew that Dick wanted to die–he told me so while he still could–and so I suppose I should be glad that his suffering is now over. Yet I find it impossible to greet the news of his death with anything other than black sorrow, though I know that it will someday be a comfort to have his books to read and his records to play. When I heard that he was dying, I sat quietly in my hotel room for a few minutes, then opened up my iBook and listened to the sweetly elegiac performance of Duke Ellington’s “Black Butterfly” that he recorded with Roger Kellaway in 1999 (it’s on Melodies Heard, Melodies Sweet). It isn’t given to very many of us to write our own epitaphs, much less play them, but I can’t think of a better way to sum up what Dick Sudhalter was all about than to listen to that song.

I knew that Dick wanted to die–he told me so while he still could–and so I suppose I should be glad that his suffering is now over. Yet I find it impossible to greet the news of his death with anything other than black sorrow, though I know that it will someday be a comfort to have his books to read and his records to play. When I heard that he was dying, I sat quietly in my hotel room for a few minutes, then opened up my iBook and listened to the sweetly elegiac performance of Duke Ellington’s “Black Butterfly” that he recorded with Roger Kellaway in 1999 (it’s on Melodies Heard, Melodies Sweet). It isn’t given to very many of us to write our own epitaphs, much less play them, but I can’t think of a better way to sum up what Dick Sudhalter was all about than to listen to that song.

UPDATE: Doug Ramsey, another of Dick’s friends, pays eloquent tribute to him here.

This posting from the Chicago Reader‘s media blog tells of another slice of Dick’s life, one about which I knew little–his work as a foreign correspondent.

The New York Times obituary is here.

The Washington Post obituary is here.

Further thoughts from Patrick Kurp at Anecdotal Evidence.

OGIC: A friend remembers Wallace

Adding to Carrie’s thoughts about David Foster Wallace’s shocking suicide is my friend Erin Hogan, author of the land-art travelogue Spiral Jetta and the most impassioned Wallace reader I know.

It seems only fair to start a few words about David Foster Wallace by talking about myself. No other writer was as deeply invested in individual consciousness–and its ridiculously messy, digressive, splintering course–as DFW. The individual consciousness that is me received so many condolence calls about Wallace’s suicide on Saturday and Sunday that I began to feel I had some sort of friendship with him, though I never met him.

I was an early proponent of Infinite Jest, probably gifting it over the years to at least 20 people. As a former coworker wrote to remind me, I made familiarity with IJ a condition of employment in my department. I believed–and still believe–that no other novel comes close to engaging with the welter of sights, sounds, fears, smells, absurdities, and beauty of our time. It’s a sprawling, sickening, hilarious mess, and many people have taken it to be DFW’s definite work. And why wouldn’t they? At nearly 1100 pages, the last leg of them footnotes, it is a magnum opus. Others have pointed to his essays–on tennis, cruise ships, television, language, state fairs–where DFW seemingly harnessed his impulses to overwhelm and emerged with biting, incisive, and yet sympathetic views of contemporary life. They were essays in the truest sense, essais, attempts, tries to explain, to elucidate arcane sports skills or how vacation alienation points to a fundamental human pathos.

But I always found DFW most in his short stories. I should say immediately that I am not a natural fan of the genre. Even the best short stories seem to me too short. They don’t allow a reader an immersive experience, which is the kind of experience I am always looking for. DFW’s story collections–particularly Brief Interviews with Hideous Men–remain for me the epitome of the genre. They push the story form to its limits, though with mixed results. There are stories that are two sentences or two paragraphs long, stories that are answers to unvoiced questions, stories that include their own scaffolding of craft, stories in the second and third person, stories that are pure dialogue. They are stories of nearly unspeakable tragedy and horror, and stories of unbearable beauty. Sentences I first read in these stories–“Metal flowers bloom on your tongue” (“Forever Overhead”), “All this according to Dirk of Fresno” (which always makes me laugh, from “Tri-Stan: I Sold Sissee Nar to Ecko”), “His own forehead snaps clear” (“Think”)–are still with me.

I could say that I think Wallace loved language and detail and work, prolific work, all of which are clear in everything he did. But it is in his stories that his ethical agenda is clear. He’s not racking up these gruesome details to disgust us; he is empathetically portraying the worst that humans can offer to each other. He’s not using footnotes because it’s clever; he’s using footnotes because it they are the closest approximations in a literary form to the mass of nonlinear parenthetical thoughts that is the monkey brain of all of us doing its job. He’s not using that vocabulary of his to show off; he’s using it because the world is bursting to be described fully. I think I once heard him say that literature teaches us how to be human. By this I think he meant that the role of literature is to stretch our understanding of the hideous and the glorious; embrace the ambivalence, the mess; be attentive even when the stimuli are too much to bear; and understand that beneath all of this–these words, these betrayals and misdeeds, this ugliness and absurdity–lies the essentially human.

Maybe I didn’t hear him say this, but he probably wouldn’t care. I’m a reader, not a writer, so many more people will have a lot more intelligent things to say about him. But I cried when I heard the news. It was only then that I realized I was looking forward to growing old with him, hearing what he had to say about aging, Obama, the millennium, California, Rafael Nadal, cookies, anxiety, reality television, love, hybrid cars–everything under his sun. I am so grateful that he shared what he had, that he suffered through his struggles long enough to gift us with what he did.

Terry wrote about Spiral Jetta for Commentary’s blog here. This New York Times review found the book pretty great, too. Thanks to Erin for sharing her thoughts.

TT: Revolutionary bore

This week I review three shows in my Wall Street Journal drama colum, one on Broadway and two in Cape May, New Jersey. The Broadway premiere of A Tale of Two Cities is an expensive dud, while Cape May Stage’s Doubt and the East Lynne Theatre Company’s To the Ladies are both top-notch. Go figure! Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

If you loved “Les Misérables,” you’ll like “A Tale of Two Cities.” The book is earnest, the décor elaborate, the cast hard-working. I wish I could summon up somewhat more enthusiasm for Jill Santoriello’s musical version of Charles Dickens’ great novel of the French Revolution, but except for Tony Walton’s ingenious quick-change sets and James Barbour’s magnetic performance as Sydney Carton, the first show of the Broadway season is a protracted exercise in plodding mediocrity that’s as sincere as a Sunday sermon and several times longer to boot.

Authorially speaking, “A Tale of Two Cities” is a one-woman show. Ms. Santoriello, a Broadway debutante, wrote the book, an overstuffed digest of Dickens’ eventful novel, and the songs, whose lyrics are gimcrack and whose music consists of dull tunes that have been bulked up in vain with rolling cymbals and thundering timpani….

Cape May Stage performs in a deconsecrated Presbyterian church whose ecclesiastical yet intimate air enhances the effectiveness of its superb production of “Doubt,” John Patrick Shanley’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play about a Roman Catholic priest (Paul Bernardo) who may or may not have molested a child in his care. I saw “Doubt” at what I took for granted would be a disadvantage, since Brían F. O’Byrne, Cherry Jones, Heather Goldenhersh and Adriane Lenox, the stars of the original New York production, gave bravura performances that still stand out in my memory. Imagine my surprise, then, when Mr. Bernardo, Mary Baird, Abby Royle and Sameerah Luqmaan-Harris, all of whose names are new to me, turned out to be every bit as good as their better-known predecessors….

Cape May Stage performs in a deconsecrated Presbyterian church whose ecclesiastical yet intimate air enhances the effectiveness of its superb production of “Doubt,” John Patrick Shanley’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play about a Roman Catholic priest (Paul Bernardo) who may or may not have molested a child in his care. I saw “Doubt” at what I took for granted would be a disadvantage, since Brían F. O’Byrne, Cherry Jones, Heather Goldenhersh and Adriane Lenox, the stars of the original New York production, gave bravura performances that still stand out in my memory. Imagine my surprise, then, when Mr. Bernardo, Mary Baird, Abby Royle and Sameerah Luqmaan-Harris, all of whose names are new to me, turned out to be every bit as good as their better-known predecessors….

Unlike Cape May Stage, which offers the usual summer-theater mix of straight plays and small-scale musicals, the East Lynne Theater Company specializes in shows that “deal with the uniquely American experience,” including revivals of forgotten American plays from the first half of the 20th century. This year the company has exhumed “To the Ladies,” a 1922 comedy by George S. Kaufman and Marc Connelly. All Kaufman-Connelly revivals are rare–Kaufman is now remembered solely for his later collaborations with Moss Hart–but “To the Ladies” hasn’t been staged anywhere since 1926, which makes this production significant by definition.

To be sure, I expected that “To the Ladies” would be a historical curiosity, but it turns out to be a thoroughly likable piece of proto-feminist fluff about a pair of bumbling businessmen (John Morton and Ken Glickfeld) and the brainy wives (Tiffany-Leigh Moskow and Suzanne Dawson) who repeatedly pull them out of the holes they dig for themselves.

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Almanac

“Criticism is a study by which men grow important and formidable at very small expense. The power of invention has been conferred by nature upon few, and the labour of learning those sciences which may, by mere labour, be obtained, is too great to be willingly endured; but every man can exert some judgment as he has upon the works of others; and he whom nature has made weak, and idleness keeps ignorant, may yet support his vanity by the name of critic.”

Samuel Johnson, The Idler, No. 60

OGIC: Second stories

Patrick Kurp, whose blog I recommended yesterday, posted the other day about the necessity of gratitude and about W. H. Auden: “Auden’s instinct was to offer thanks for the gifts he, like all of us, had done nothing to deserve.” The post resonated with an almost throwaway sentence I read recently in Edward P. Jones’s The Known World. This is very much how it is, reading Jones: peripheral details about peripheral characters, mentioned in passing, have the weight and pull of miniature stories in their own right. These stories might, in a half-sentence, be told, or they might be only gestured at. Through them a sense of the whole vast, connected world slips in, of its enormity and of the numberless threads of human plots therein. The effect, over pages and chapters, is not only of richness and plenitude but of a great humaneness–Jones’s and, the more you read of him, your own.

Jones’s novel is about slaves and slave owners in pre-Civil War America. In the passage I was reminded of, the young Virginian John Skiffington, who on principle owns no slaves, has just married a Northern woman. To the profound discomfort of half the wedding party, a cousin of the groom has made a wedding gift of a nine-year-old slave girl, Minerva. The next morning, her first in the house, Minerva rises early and tiptoes around her new surroundings.

The child now took more steps, passing her own room, and came to a partly opened door. She could see John Skiffington’s father on his knees praying in a corner of his room. Fully dressed with his hat on, the old man, who would find another wife in Philadelphia, had been on his knees for nearly two hours: God gave so much and yet asked for so little in return.

This fleeting narrative detour is lovely and painful at once: lovely for the humble and surprising act of gratitude it records, painful for being observed by someone not so fortunate. We don’t hear a lot more about the elder Mr. Skiffington, at least not as far as I’ve read, and that only makes this impromptu glimpse the more poignant.

Nobody else I’ve read is like Jones. He’s an unmatched teller of stories big and small–he’ll hook you on the stuff. His short stories in All Aunt Hagar’s Children had me over the moon when I read and reviewed them two years ago. The stories and the novel deal with some of the darker aspects of human experience; they look at this material hard and straight on. But there are always points of grace amidst the pain that are the most indelible moments, and the whole enterprise is characterized by a generosity toward humanity that isn’t ever blindered or phony. Definitely a writer to be grateful for.

TT: So you want to see a show?

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

Warning: Broadway shows marked with an asterisk were sold out, or nearly so, last week.

BROADWAY:

• Alfred Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps (comedy, G, suitable for bright children, reviewed here)

• August: Osage County (drama, R, adult subject matter, reviewed here)

• Avenue Q (musical, R, adult subject matter and one show-stopping scene of puppet-on-puppet sex, reviewed here)

• Boeing-Boeing (comedy, PG-13, cartoonishly sexy, reviewed here)

• Gypsy (musical, PG-13, adult subject matter, reviewed here)

• The Little Mermaid * (musical, G, entirely suitable for children, reviewed here)

• South Pacific * (musical, G/PG-13, some sexual content, brilliantly staged but unsuitable for viewers acutely allergic to preachiness, reviewed here)

OFF BROADWAY:

• Enter Laughing (musical, PG-13, closes Oct. 12, reviewed here)

• Enter Laughing (musical, PG-13, closes Oct. 12, reviewed here)

• The Fantasticks (musical, G, suitable for children capable of enjoying a love story, reviewed here)

IN HARTFORD, CONN.:

• A Midsummer Night’s Dream (comedy, G, surprisingly child-friendly, closes Oct. 5, reviewed here)

IN SPRING GREEN, WISC.:

• A Midsummer Night’s Dream/Widowers’ Houses (comedies, G, playing in repertory through Oct. 5, reviewed here)

CLOSING NEXT WEEK OFF BROADWAY:

• Around the World in 80 Days (comedy, G, closes Sept. 28, reviewed here)

CLOSING FRIDAY IN EAST HADDAM, CONN.:

• Half a Sixpence (musical, G, reviewed here)