The “Public Melody Number One” musical sequence from Raoul Walsh’s 1937 film Artists and Models, staged by Vincente Minnelli and featuring Louis Armstrong and Martha Raye. Raye darkened her skin with makeup in order to appear on screen with Armstrong:

(This is the latest in a weekly series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Wednesday.)

Archives for 2008

TT: Almanac

“One is safe if one is still able to risk.”

Helen Frankenthaler (quoted in the New York Times, Apr. 27, 2003)

TT: The eleventh day of the eleventh month

On October 9, 1918, an HMV sound engineer named Will Gaisberg set up a primitive piece of recording equipment immediately behind a unit of the Royal Garrison Artillery stationed outside Lille and recorded a British gas-shell bombardment. His purpose in doing so was to preserve the sounds of war before the coming armistice caused them to vanish forever from the face of the earth.

On October 9, 1918, an HMV sound engineer named Will Gaisberg set up a primitive piece of recording equipment immediately behind a unit of the Royal Garrison Artillery stationed outside Lille and recorded a British gas-shell bombardment. His purpose in doing so was to preserve the sounds of war before the coming armistice caused them to vanish forever from the face of the earth.

According to HMV’s catalogue, the recording, which was commercially released, consisted of

the actual reproduction of the screaming and whistling of the shells previous to the entry of the British troops into Lille. It is not an imitation but was recorded on the battlefront. The report of the guns and the whistling of the shells is the actual sound of the Royal Garrison Artillery in action on October 9th, 1918. No book or picture can ever visualise the reality of modern warfare just the way this record has done…it would require only the slightest imagination for one, by means of this record, to be projected into the past, and feel that he is really present on the battlefield witnessing this historic chapter of the war.

Here is Gaisberg’s own account of the making of the recording:

Gradually we came within the sound of the guns, and eventually, when only a short distance from Lille, we pulled up at a row of ruined cottages, in one of which the heavy siege battery had made its quarters. In the wrecked kitchen we unpacked our recording machines and made our preparations before getting directly behind a battery of great 4.5′ guns and 6′ howitzers, camouflaged until they looked at close quarters like giant insects. Here the machine could well catch the finer sounds of the “singing,” the “whine,” and the “scream” of the shells, as well as the terrific reports when they left the guns.

Dusk fell, and we were obliged, very reluctantly, to pack up our recording instrument and return to Boulogne–and to England; but we brought with us a true representation of the bombardment, which will have a unique place in the history of the Great War.

You can download the two-minute-long recording from iTunes by searching for “Gas Shells Bombardment.” It is one of the most haunting and disturbing documents of the past that I know–one made all the more haunting by the knowledge that Gaisberg accidentally inhaled some of the gas from the attack, which damaged his lungs irreparably. In London he fell victim to the international flu epidemic that was then ravaging the city, and died on November 5, six days before World War I came to an end.

You can download the two-minute-long recording from iTunes by searching for “Gas Shells Bombardment.” It is one of the most haunting and disturbing documents of the past that I know–one made all the more haunting by the knowledge that Gaisberg accidentally inhaled some of the gas from the attack, which damaged his lungs irreparably. In London he fell victim to the international flu epidemic that was then ravaging the city, and died on November 5, six days before World War I came to an end.

Ninety years later, only ten veterans of what Woodrow Wilson called “the War to End War,” one of whom is an American, are still alive. If you think of them today–and you should–take a moment to think about Will Gaisberg as well.

* * *

HMV D378, “Actual Recording of the Gas Shell Bombardment, by the Royal Garrison Artillery (9th October, 1918), preparatory to the British Troops entering Lille”:

TT: Good old days

A new friend of mine who dances for a living wrote the other day to tell me that she’s just been cast as the Woman With the Purse in Jerome Robbins’ Fancy Free, the wonderful 1943 sailor-suit ballet that made stars out of Robbins and Leonard Bernstein, who wrote the delicious and irresistible score. Her e-mail reminded me of how rarely I get to dance performances these days. The publication in 2004 of All in the Dances, my brief life of George Balanchine, turned out in the short run to be an end rather than a beginning: more than a year has gone by since I last saw New York City Ballet, and even longer since my most recent visit to the Paul Taylor Dance Company, both of which used to be central to my hectic life as a peripatetic aesthete. Alas, I’m good for only so many nights out each week, and now that I’m a full-time drama critic and part-time opera librettist, I’ve been forced to put dance on the shelf, at least for the time being.

A new friend of mine who dances for a living wrote the other day to tell me that she’s just been cast as the Woman With the Purse in Jerome Robbins’ Fancy Free, the wonderful 1943 sailor-suit ballet that made stars out of Robbins and Leonard Bernstein, who wrote the delicious and irresistible score. Her e-mail reminded me of how rarely I get to dance performances these days. The publication in 2004 of All in the Dances, my brief life of George Balanchine, turned out in the short run to be an end rather than a beginning: more than a year has gone by since I last saw New York City Ballet, and even longer since my most recent visit to the Paul Taylor Dance Company, both of which used to be central to my hectic life as a peripatetic aesthete. Alas, I’m good for only so many nights out each week, and now that I’m a full-time drama critic and part-time opera librettist, I’ve been forced to put dance on the shelf, at least for the time being.

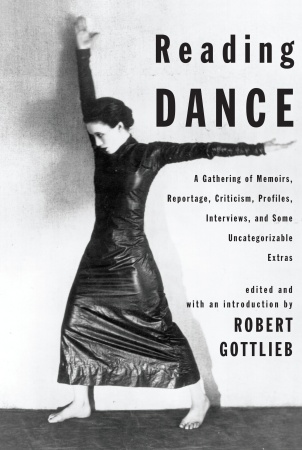

Hence it is with a mixture of nostalgia and wistfulness that I announce the publication of Robert Gottlieb’s Reading Dance: A Gathering of Memoirs, Reportage, Criticism, Profiles, Interviews, and Some Uncategorizable Extras, a thirteen-hundred-page anthology whose subtitle is impeccably accurate. Reading Dance contains pieces about Balanchine, Robbins, Frederick Ashton, Fred Astaire, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Serge Diaghilev, Isadora Duncan, Suzanne Farrell, Martha Graham, Gelsey Kirkland, Mark Morris, Vaslav Nijinsky, Rudolf Nureyev, Paul Taylor, Twyla Tharp and dozens of other key figures in dance. The list of contributors includes Joan Acocella, Mindy Aloff, Cecil Beaton, Cyril Beaumont, Max Beerbohm, Toni Bentley, Holly Brubach, Richard Buckle, Clement Crisp, Arlene Croce, Edwin Denby, Janet Flanner, Lynn Garafola, Robert Greskovic, B.H. Haggin, Deborah Jowitt, Allegra Kent, Lincoln Kirstein, Alistair Macaulay, George Jean Nathan, Jean Renoir, Marcia Siegel, Paul Taylor, Tobi Tobias, Kenneth Tynan, David Vaughan, and my old friend Anita Finkel, whose premature and untimely death robbed the world of dance of one of its most passionate commentators.

Hence it is with a mixture of nostalgia and wistfulness that I announce the publication of Robert Gottlieb’s Reading Dance: A Gathering of Memoirs, Reportage, Criticism, Profiles, Interviews, and Some Uncategorizable Extras, a thirteen-hundred-page anthology whose subtitle is impeccably accurate. Reading Dance contains pieces about Balanchine, Robbins, Frederick Ashton, Fred Astaire, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Serge Diaghilev, Isadora Duncan, Suzanne Farrell, Martha Graham, Gelsey Kirkland, Mark Morris, Vaslav Nijinsky, Rudolf Nureyev, Paul Taylor, Twyla Tharp and dozens of other key figures in dance. The list of contributors includes Joan Acocella, Mindy Aloff, Cecil Beaton, Cyril Beaumont, Max Beerbohm, Toni Bentley, Holly Brubach, Richard Buckle, Clement Crisp, Arlene Croce, Edwin Denby, Janet Flanner, Lynn Garafola, Robert Greskovic, B.H. Haggin, Deborah Jowitt, Allegra Kent, Lincoln Kirstein, Alistair Macaulay, George Jean Nathan, Jean Renoir, Marcia Siegel, Paul Taylor, Tobi Tobias, Kenneth Tynan, David Vaughan, and my old friend Anita Finkel, whose premature and untimely death robbed the world of dance of one of its most passionate commentators.

I am represented in Reading Dance by “Pale Horse, Pale Rider,” an essay about Merce Cunningham that was originally published in Anita’s New Dance Review in 1994 and reprinted a decade later in A Terry Teachout Reader. Revisiting that half-remembered piece filled me with memories of the heady years when it was common for me to attend three or four ballet and modern dance performances a week. Back then my first encounters with Balanchine, Cunningham, and Taylor were still hitting me with the force of revelation, and I felt the urgent need to write as often as I could about the life-changing things that I was seeing–and feeling.

Needless to say, my life has changed greatly since then, but I still love dance with all my heart, and I’m glad that Bob Gottlieb has gone to so much trouble to tell me what I’ve been missing. I’ll be back, Bob, I promise!

TT: Words to the wise

• “John Marin: Ten Masterworks in Watercolor” goes up next Thursday at Meredith Ward Fine Art and will be on display through Dec. 20. The show consists of ten works on paper by the pioneering American modernist whose virtuosity in the watercolor medium remains unrivaled. Some are from Marin’s estate, others from private collections, and most are familiar only to Marin specialists. It’s been a number of years since any of Marin’s watercolors were last on view in Manhattan, making this a rare opportunity to experience a great American painter at the peak of his powers.

• “John Marin: Ten Masterworks in Watercolor” goes up next Thursday at Meredith Ward Fine Art and will be on display through Dec. 20. The show consists of ten works on paper by the pioneering American modernist whose virtuosity in the watercolor medium remains unrivaled. Some are from Marin’s estate, others from private collections, and most are familiar only to Marin specialists. It’s been a number of years since any of Marin’s watercolors were last on view in Manhattan, making this a rare opportunity to experience a great American painter at the peak of his powers.

For more information, go here.

• The Maria Schneider Orchestra, to which regular readers of this blog need no introduction, will be performing Nov. 25-30 (except for Thanksgiving) at the Jazz Standard. It’s become a tradition of sorts for Maria and her big band to set up shop at the Jazz Standard during Thanksgiving week. Alas, they don’t appear nearly often enough in the New York area, so tables are likely to be snapped up fast. Don’t delay–reserve today.

For more information, go here and scroll down.

• Speaking of my favorite New York nightclub, Roger Kellaway’s Live at the Jazz Standard, a two-CD set from IPO Recordings, was released today. I wrote the liner notes, which are based on a posting that I knocked out immediately after coming home from the opening night of the 2006 engagement at which this album was recorded:

Kellaway is currently fronting a piano-guitar-bass trio, which he claims to be the fulfillment of a “childhood dream.” Oscar Peterson led just such a group in the Fifties, and Kellaway, a lifelong Peterson fan who has always enjoyed playing without a drummer, knows how to make the most of the elbow room afforded by that wonderfully flexible instrumentation. Russell Malone is the guitarist, Jay Leonhart the bassist. The three men opened the set with a super-sly version of Benny Golson’s “Killer Joe,” and within four bars you knew they were going to swing really, really hard. So they did, with Kellaway pitching his patented curve balls all night long, including a bitonal arrangement of Bobby Darin’s “Splish Splash” and what surely must have been the first time that the Sons of the Pioneers’ “Tumbling Tumbleweeds” has ever been performed by a jazz group.

Everybody in the band (including vibraphonist Stefon Harris, who joined the trio for “Cotton Tail,” “You Don’t Know What Love Is” and “52nd Street Theme”) was smoking. Kellaway, though, was…well, I really don’t have words to describe the proliferating creativity and rhythmic force of his piano playing. Sarah did pretty well, though: “Did you see my jaw drop?” she asked me when it was all over. Russell Malone, with whom I chatted between sets, put it even more tersely. “That man is scary,” he said, shaking his head.

Yes, it was that good and then some, and then some more–and now you can hear what you missed.

TT: Almanac

“Pictures can work perfectly; life cannot.”

Helen Frankenthaler (quoted in The Art Newspaper, June 2000)

ENTER, STAGE RIGHT?

“When the curtain goes up, I don’t care whether the author of the show I’m about to see is a Republican, a Democrat, an anarchist or a drunkard, so long as he’s taken the advice of Anton Chekhov: ‘Anyone who says the artist’s field is all answers and no questions has never done any writing….It is the duty of the court to formulate the questions correctly, but it is up to each member of the jury to answer them according to his own preference.’ That’s what great playwrights do: They put a piece of the world on stage, then step out of the way and leave the rest to you…”

TT: Image #31

Louis Armstrong was not only a great artist but one of the brightest stars in the sky of America’s popular culture. One of the signs of his admittance to that pantheon was the frequency with which Al Hirschfeld drew him. For most of his long lifetime, Hirschfeld was America’s best-known and most successful caricaturist. To be drawn by him was like being the mystery guest on What’s My Line? It meant that you’d really, truly arrived.

So far as I know, Armstrong first achieved that distinction in 1939, the year that he played Bottom on Broadway in Swingin’ the Dream, a swing-era musical version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream that closed after just thirteen performances. Hirschfeld drew him for the New York Times that season. The failure of Swingin’ the Dream put an end to his brief stage career, but not to his popularity, and from then on he would figure prominently in Hirschfeld’s gallery of celebrities.

So far as I know, Armstrong first achieved that distinction in 1939, the year that he played Bottom on Broadway in Swingin’ the Dream, a swing-era musical version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream that closed after just thirteen performances. Hirschfeld drew him for the New York Times that season. The failure of Swingin’ the Dream put an end to his brief stage career, but not to his popularity, and from then on he would figure prominently in Hirschfeld’s gallery of celebrities.

I wanted very much to include a Hirschfeld caricature of Louis Armstrong in A Cluster of Sunlight, my Armstrong biography, both as an indication of his renown and because Hirschfeld’s portrayals of Armstrong are vividly suggestive of the way in which he was perceived by the public at large. In the prologue to A Cluster of Sunlight, I talk about the contrast between “the grinning jester with the gleaming white handkerchief who sang ‘Hello, Dolly!’ and ‘What a Wonderful World’ night after night for adoring audiences” and the private man whom I got to know by listening to the private conversations that he taped for posterity throughout the last quarter-century of his life:

Off stage he could be moody and profane, and he knew how to hold a grudge. “I got a simple rule about everybody,” he told a journalist. “If you don’t treat me right–shame on you!” While he was anything but cynical, he had no illusions about the world in which he lived, whose follies he summed up with pointed wit. A friend dropped in on him after a gig and asked what was new. “Nothin’ new,” he said. “White folks still ahead.” He was as clear-headed about his own fame: “I can’t go no place they don’t roll up the drum, you have to stand up and take a bow, get up on the stage. And sitting in an audience, I’m signing programs for hours all through the show. And you got to sign them to be in good faith. And afterwards all those hangers-on get you crowded in at the table–and you know you’re going to pay the check.”

At the same time, I learned in the course of writing my book that Armstrong’s public face was not a mask. Though he was more complicated than he let on, he was in the end what he seemed to be, an essentially happy man who lived to give pleasure to his fans. In later years, to be sure, his minstrel-show mugging made many younger Americans uncomfortable, black and white alike. Ossie Davis, who co-starred with Armstrong in his next-to-last feature film, Sammy Davis Jr.’s A Man Called Adam, detested his good-humored clowning and wrote sharply about it: “Everywhere we’d look, there’d be Louis–sweat popping, eyes bugging, mouth wide open, grinning, oh my Lord, from ear to ear….mopping his brow, ducking his head, doing his thing for the white man.” But Armstrong’s stage persona was part of who he was, and it is impossible to understand him without accepting that fact and coming to terms with it.

The Armstrong whom Al Hirschfeld drew was the Armstrong whom Ossie Davis hated–and he wasn’t alone. One of the things that I discovered while researching my book was that Time commissioned a Hirschfeld caricature of Armstrong in 1998 that the editors chose not to publish after black staffers at the magazine complained that it was racially insensitive. While I didn’t include this story in A Cluster of Sunlight because it was peripheral to the narrative, it made me feel even more strongly that I needed to reproduce one of Hirschfeld’s caricatures in my book in order to provide the fullest possible context for my discussion of the changing ways in which black and white listeners perceived Armstrong throughout his long career.

The caricature that I had in mind was drawn in 1991. It is one of Hirschfeld’s most complex and evocative pieces of portraiture, a little-known color lithograph called “Satchmo!” that embodies what Philip Larkin once called “the stageshow Armstrong” more completely than any drawing of Louis Armstrong that I have ever seen–and I’ve seen plenty.

To be sure, I have no doubt that some contemporary viewers will see in “Satchmo!” the Armstrong to whom Shelby Steele referred in A Bound Man, his 2007 book about Barack Obama:

The relentlessly beaming smile, the handkerchief dabbing away the sweat, the reflexive bowing, the exaggerated humility and graciousness–all this signaled that he would not breach the manners of segregation, the propriety that required him to be both cheerful and less than fully human.

But I see another Armstrong in Hirschfeld’s drawing, the one whom the black jazz pianist Jaki Byard knew and loved. “As I watched him and talked with him, I felt he was the most natural man,” Byard said. “Playing, talking, singing, he was so perfectly natural the tears came to my eyes.”

Who is right? That’s for the reader of A Cluster of Sunlight to decide, which is why I paid a visit last Wednesday to the Margo Feiden Galleries, the representatives of Al Hirschfeld’s estate. I was anxious, having been told more than once that it was difficult and costly to obtain permission to reproduce Hirschfeld’s caricatures. Neither proved to be true. Within a matter of minutes, the deal was done, and I spent the remainder of my visit inspecting the gallery, whose walls are thickly hung with original caricatures, many of them of well-known jazz musicians (Duke Ellington was another of Hirschfeld’s preferred subjects).

Image #31, as “Satchmo!” is now known to Harcourt, my publisher, will be the final photograph reproduced in A Cluster of Sunlight. This is the caption I wrote for it:

“Grinning, oh my Lord, from ear to ear”: Many now feel ill at ease with the old-fashioned, crowd-pleasing entertainer portrayed in this 1991 caricature by Al Hirschfeld, but there was nothing false about Satchmo’s unselfconscious smile.

I hope you agree.

Incidentally, the subtitle of Shelby Steele’s book was Why We Are Excited About Obama and Why He Can’t Win. He was wrong about that, too.