“We are always on stage, even when we are stabbed in earnest at the end.”

Georg Büchner, Danton’s Death (trans. Gerhard P. Knapp)

Archives for 2008

OGIC: Killing me softly

I’m really obsessed with Keats’s “To Autumn”; I think it’s a perfect and magical piece of writing, with effects that resonate and evolve for a lifetime. I got familiar with the poem in my first year of graduate school, when I took a memorable course called “Keats and Critique.” The course explored the premise–popular among the Victorians who installed him belatedly as a great English poet–that Keats was done in, in part, by his bad reviews. And it’s true that when they were bad, they were vicious.

When I reread this poem–or, as lately, recite it and write it out as outlets for its hold upon my ear and brain–I fend off impulses to thrust it upon innocent passers-by, pointing out its most bewitching features. I don’t so much have a reading of it as a set of things I notice in it, a collection that grows slowly over the years. Here are just a few of these amateur observations, truly off the top of my head; consider yourself one of those unsuspecting bystanders.

The first stanza describes an ample, apparently endless autumn bounty.

Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun;

Conspiring with him how to load and bless

With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run;

To bend with apples the moss’d cottage-trees,

And fill all fruit with ripeness to the core;

To swell the gourd, and plump the hazel shells

With a sweet kernel; to set budding more,

And still more, later flowers for the bees,

Until they think warm days will never cease,

For summer has o’er-brimmed their clammy cells.

Throughout the poem there’s a (deceptive) sense that time is suspended. In this stanza, that’s accomplished in large measure by the repeated use of infinitive verbs: “to load and bless”; “to bend”; “[to] fill”: “to swell”; “[to] plump”; “to set.” The last line, explaining how the bees are fooled, links this sense of time drawn out to the abundance described throughout the stanza. Tees bent under the weight of fruit, the filling, swelling, plumping, budding, overbrimming of nature–all of this burgeoning–is mimicked in the poem’s language, where phrases spill over the bounds of their lines and a gratuitous second instance of “more” in line nine performs the word’s own meaning. The stanza is literally fruitful: “fruit” appears three times in its 11 lines, including an instance as something that fills (vines) and one as something that is filled (with ripeness).

The next stanza switches gears, presenting autumn as an allegorical figure.

Who hath not seen thee oft amid thy store?

Sometimes whoever seeks abroad may find

Thee sitting careless on a granary floor,

Thy hair soft-lifted by the winnowing wind;

Or on a half-reap’d furrow, sound asleep,

Drows’d with the fume of poppies while thy hook

Spares the next swath and all its twined flowers:

And sometimes like a gleaner thou dost keep

Steady thy laden head across a brook;

Or by a cyder-press, with patient look,

Thou watchest the last oozings hours by hours.

Again, time is on hold. The personified Autumn is an indolent creature, “sitting careless” in a workplace, “sound asleep” in the fields, watching the press rather than operating it. Even in the most industrious of the four attitudes described here, she is only like a gleaner. The work of her hook, in her previous guise, is to “spare”; it’s at rest. All of this is in contrast with the busy industry of the first stanza, though the sense of time stood still persists. Until that last line, that is, when a sense of ending finally sets in–in the “last oozings,” significant both for the adjective’s meaning and for the noun’s sound, and in the invocation of hours. There’s also the gently diminishing length of the four views of Autumn offered here: they fill three lines, three lines, two, and two. (Note, though, they stop short of approaching zero.)

The third and last stanza masterfully dissolves into sounds, capturing a last, momentary stasis before winter sets in.

Where are the songs of spring? Ay, where are they?

Think not of them, thou hast thy music too,–

While barred clouds bloom the soft-dying day,

And touch the stubble-plains with rosy hue;

Then in a wailful choir the small gnats mourn

Among the river sallows, borne aloft

Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies;

And full-grown lambs loud bleat from hilly bourn;

Hedge-crickets sing; and now with treble soft,

The red-breast whistles from a garden-croft;

And gathering swallows twitter in the skies.

There are so many interesting things going on here. The use of “bloom” as a transitive verb; the singular, whistling red-breast set against the plural plains, gnats, sallows, lambs, crickets, swallows, and skies; the seemingly unnecessary designation of the gnats as “small.” Autumn’s music, it must be said, is a gentle, symphonic, glorious, consoling…dirge. “Soft-dying” describes not only the day but the season and the year as viewed through the prism of this poem, and by extension human life (it also provides a coda to the soft-lifting of stanza two). From its flirting with the notion of birth, through the use of the homophones “borne” and “bourn” (not to mention rhyming them with “mourn”), to the invocation of lambs on the threshold of adulthood and a wind that flits easily from death to life, it looks to the seasonal cycle for consolation for the life-cycle. It tries to touch mortality with rosy hue. It softens you up for the final blow, which takes place off the page–delivered, we imagine, softly.

P.S. By coincidence, Anecdotal Evidence also posts on Keats, death, and beauty today.

TT: Clive Barnes, R.I.P.

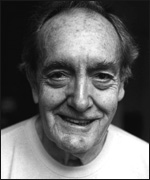

When I was a teenager and first became aware of criticism as a profession, Clive Barnes was one of its very biggest names. Born in 1927, Barnes had come to this country in 1965 to work for the New York Times. Right from the start, he was the kind of writer who got written about, in part because he had two arrows in his critical quiver: he covered dance and theater, and did so with self-evident relish. At some point it occurred to me that I, too, might want to write about more than one subject, and I have no doubt that Barnes’ example was part of what inspired me to do so.

When I was a teenager and first became aware of criticism as a profession, Clive Barnes was one of its very biggest names. Born in 1927, Barnes had come to this country in 1965 to work for the New York Times. Right from the start, he was the kind of writer who got written about, in part because he had two arrows in his critical quiver: he covered dance and theater, and did so with self-evident relish. At some point it occurred to me that I, too, might want to write about more than one subject, and I have no doubt that Barnes’ example was part of what inspired me to do so.

I discovered ballet in 1987 and started writing about it for The New Dance Review shortly thereafter. That was when I first recognized Barnes as a physical presence, sitting on the aisle of virtually every first night that I attended. Sixteen years later I became the drama critic of The Wall Street Journal and joined the New York Drama Critics’ Circle, of which Barnes and John Simon were the senior members. It seemed utterly improbable to me that I should be casting votes alongside men whose reviews I’d been reading for the better part of four decades, much less calling them by their first names. I found Clive to be perfectly friendly and collegial, but by then it was impossible for me to shed the diffidence of my long-lost youth and get to know him more than casually. To me he was Clive Barnes, and that was that.

Clive’s byline recently disappeared from the New York Post, to which he had moved in 1978, and the paper’s dance and drama reviews started carrying an ominous tagline: Clive Barnes is on leave. This morning a mutual friend passed the not-surprising word that he had died of liver cancer. Almost to the end, though, he clung to his aisle seat, and as late as two weeks ago he was still filing reviews that left no doubt of his undiminished appetite for ballet, the art that he loved most and knew best. That’s the best of all possible epitaphs for a long-lived critic.

UPDATE: The New York Times obituary is here.

The New York Post obituary is here.

TT: Snapshot

Sid Caesar and Nanette Fabray engage in a pantomime argument on a 1954 episode of Caesar’s Hour, accompanied by the first movement of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony:

(This is the latest in a weekly series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Wednesday.)

TT: Almanac

“The distinction between the two types of art is a difference of density rather than of species. In the same number of bars of Beethoven and Sousa, there is, in Beethoven, more of the essence of music, giving a thicker, more intense effect likely to alienate the unfamiliar listener by ‘boring’ him, just as the palate accustomed to that richer food is bored by the thinness of the popular tune. The feeling that this is not the only difference is due to the fact that as an art grows more and more complex and dense, the number of relations among simple elements increases until those relations look like extraordinarily refined experiences denied to the common herd. Yet there is no real barrier to be leaped over by an effort of genius between understanding a ‘vulgar’ dance tune and a Beethoven symphony.”

Jacques Barzun, Of Human Freedom

TT: Eavesdropping on Tom Stoppard with Gwen Orel

Tom Stoppard, who might just be the greatest living English-language playwright, is in Manhattan on business, and made a couple of public appearances last week. Alas, I was unavoidably elsewhere, but my friend Gwen Orel, who writes about theater and Celtic music for all sorts of publications on and off line, was present on both occasions, and filed this report.

Tom Stoppard, who might just be the greatest living English-language playwright, is in Manhattan on business, and made a couple of public appearances last week. Alas, I was unavoidably elsewhere, but my friend Gwen Orel, who writes about theater and Celtic music for all sorts of publications on and off line, was present on both occasions, and filed this report.

* * *

Back in the twentieth century, around 1989 or so, some Serious Theatre People averred that “Tom Stoppard is over.” The Real Thing was his Tempest, they said, his farewell to the stage. Fast forward to Rough Crossing, Arcadia, The Invention of Love, The Coast of Utopia, and Rock and Roll. Some farewell! By now Stoppard, who’s in town to rehearse his new adaptation of The Cherry Orchard at BAM, has morphed into a sort of playwright-rock idol. Accordingly, he appeared in pale (though not blue) suede shoes at two public talks last week, both of them quickly overbooked. Though he was funny and charming as usual, it was fascinating to observe what a difference a moderator made.

Back in the twentieth century, around 1989 or so, some Serious Theatre People averred that “Tom Stoppard is over.” The Real Thing was his Tempest, they said, his farewell to the stage. Fast forward to Rough Crossing, Arcadia, The Invention of Love, The Coast of Utopia, and Rock and Roll. Some farewell! By now Stoppard, who’s in town to rehearse his new adaptation of The Cherry Orchard at BAM, has morphed into a sort of playwright-rock idol. Accordingly, he appeared in pale (though not blue) suede shoes at two public talks last week, both of them quickly overbooked. Though he was funny and charming as usual, it was fascinating to observe what a difference a moderator made.

At CUNY, Stoppard was joined by Nobel Prize-winning playwright Derek Walcott for a Great Issues Forum moderated by David Nasaw, the university’s Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. Professor of American History. The topic was “Cultural Power,” and the press release said that Stoppard & Co. would be exploring “the power of culture and art in a globalizing world.” Instead, they considered the Impact and Influence of Art. Yep, said Walcott, art’s impact cannot be easily counted and measured. Yep, said Stoppard, culture is what distinguishes us as human. All interesting, but…power?

The professor was smart but all too clearly awed by his celebrated guests, who seemed in turn to adore one another. He began, promisingly, by considering the way “the world changed last Tuesday,” showing a slide of Barack Obama with a book in his hand, which turned out to be Walcott’s Collected Poems, 1948-1984. Then the poet read us Forty Acres, his new poem about Obama, commissioned by the Times of London: Out of the turmoil emerges one emblem, an engraving –/a young Negro at dawn in straw hat and overalls,/an emblem of impossible prophecy…

Asked for his reaction, Stoppard said that the poem “silenced” him–but, of course, it hadn’t, and he self-deprecatingly remarked that he could go on “speaking like a wind-up toy.” At one point he mentioned a recent New York Times article about the New York City Opera which pointed out that the Paris Opera’s budget is larger than that of the entire National Endowment for the Arts. Provocatively, he then suggested that the patronage of the rich American may “get the government off the hook.” This was power! This was culture! This was another ball dropped.

The next day, Stoppard was interiewed at BAM by David Remnick, editor of The New Yorker and author of Lenin’s Tomb, who may be the only editor in New York who hadn’t rushed out to read Isaiah Berlin justto prepare for The Coast of Utopia. Remnick actually out-Stopparded Stoppard with his wit and erudition, and the result was a chat that unlike its predecessor was fascinating, insightful, and over too soon. When Remnick said “For our last question…” Stoppard looked at his watch and looked truly disappointed.

The topic was Chekhov, but the conversation managed to get somewhere near…well, cultural power. Asked what niche his new version of The Cherry Orchard would fill, Stoppard said that directors like to have a new text in rehearsal: “Theatre is a storytelling art form–plays are palimpsests of maps on different scales.” He was “constantly looking for that elusive place where the natural utterance functions as a narrative utterance.”

Gracefully segueing from a consideration of Solzhenitsyn and Stalin to literary influence, Stoppard described his aesthetic response to newsprint and his early ambition to be a foreign correspondent and live a glamorous life. “It can be arranged,” Remnick murmured. For once Stoppard was speechless–briefly. Remnick added, “There’s a 10 p.m. to Kabul.” Then Stoppard recovered. “The St. Tropez kind of correspondent,” he replied.

Asked how working in America was different than at home, Stoppard admitted that he was less comfortable here, explaing that there was “more a sense of heavy pressure to succeed–perhaps there’s more shame in failing than there ought to be.” (Maybe that’s because they don’t publish the West End grosses every week.)

What next? Stoppard said that he’d had just about decided to start working on a screenplay for Arcadia that he would then direct when the BBC came up with the idea of adapting some novels from the nineteenth century and the Twenties–something he says that he really wants to do. Me, I hope it’s Waugh. I can’t imagine anybody channeling the glamorous war-correspondent author of A Handful of Dust better than Tom Stoppard.

TT: A traveling drama critic orders dinner for one

When Dad was on the road alone

And dined, alone, at night,

He wanted everything to be

Not passable, but right:

“A perfect baked potato

Demands the utmost care.

The only way to order steak

Is medium, not rare.”

When I was ten, I told myself:

How lucky to be grown,

To eat at fancy restaurants,

To do things on your own.

I sip my lukewarm Perrier,

A Trollope close to hand.

The waitress looks exactly like

That blonde in Freshman Band.

She smiles and serves the second course.

(Perhaps there’s too much sage?)

Suppressing shades of teenage lust,

I sigh and turn the page.

The rain descends, the Muzak purrs,

I chew my veal and think:

Just one more night and I’ll be home.

“Miss? Bring another drink.”

TT: Almanac

“If the explorer moves toward the risks of the formless and the unknown, the tourist moves toward the security of pure cliché. It is between these two poles that the traveler mediates.”

Paul Fussell, Abroad