“The distinction between the two types of art is a difference of density rather than of species. In the same number of bars of Beethoven and Sousa, there is, in Beethoven, more of the essence of music, giving a thicker, more intense effect likely to alienate the unfamiliar listener by ‘boring’ him, just as the palate accustomed to that richer food is bored by the thinness of the popular tune. The feeling that this is not the only difference is due to the fact that as an art grows more and more complex and dense, the number of relations among simple elements increases until those relations look like extraordinarily refined experiences denied to the common herd. Yet there is no real barrier to be leaped over by an effort of genius between understanding a ‘vulgar’ dance tune and a Beethoven symphony.”

Jacques Barzun, Of Human Freedom

Archives for November 2008

TT: Eavesdropping on Tom Stoppard with Gwen Orel

Tom Stoppard, who might just be the greatest living English-language playwright, is in Manhattan on business, and made a couple of public appearances last week. Alas, I was unavoidably elsewhere, but my friend Gwen Orel, who writes about theater and Celtic music for all sorts of publications on and off line, was present on both occasions, and filed this report.

Tom Stoppard, who might just be the greatest living English-language playwright, is in Manhattan on business, and made a couple of public appearances last week. Alas, I was unavoidably elsewhere, but my friend Gwen Orel, who writes about theater and Celtic music for all sorts of publications on and off line, was present on both occasions, and filed this report.

* * *

Back in the twentieth century, around 1989 or so, some Serious Theatre People averred that “Tom Stoppard is over.” The Real Thing was his Tempest, they said, his farewell to the stage. Fast forward to Rough Crossing, Arcadia, The Invention of Love, The Coast of Utopia, and Rock and Roll. Some farewell! By now Stoppard, who’s in town to rehearse his new adaptation of The Cherry Orchard at BAM, has morphed into a sort of playwright-rock idol. Accordingly, he appeared in pale (though not blue) suede shoes at two public talks last week, both of them quickly overbooked. Though he was funny and charming as usual, it was fascinating to observe what a difference a moderator made.

Back in the twentieth century, around 1989 or so, some Serious Theatre People averred that “Tom Stoppard is over.” The Real Thing was his Tempest, they said, his farewell to the stage. Fast forward to Rough Crossing, Arcadia, The Invention of Love, The Coast of Utopia, and Rock and Roll. Some farewell! By now Stoppard, who’s in town to rehearse his new adaptation of The Cherry Orchard at BAM, has morphed into a sort of playwright-rock idol. Accordingly, he appeared in pale (though not blue) suede shoes at two public talks last week, both of them quickly overbooked. Though he was funny and charming as usual, it was fascinating to observe what a difference a moderator made.

At CUNY, Stoppard was joined by Nobel Prize-winning playwright Derek Walcott for a Great Issues Forum moderated by David Nasaw, the university’s Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. Professor of American History. The topic was “Cultural Power,” and the press release said that Stoppard & Co. would be exploring “the power of culture and art in a globalizing world.” Instead, they considered the Impact and Influence of Art. Yep, said Walcott, art’s impact cannot be easily counted and measured. Yep, said Stoppard, culture is what distinguishes us as human. All interesting, but…power?

The professor was smart but all too clearly awed by his celebrated guests, who seemed in turn to adore one another. He began, promisingly, by considering the way “the world changed last Tuesday,” showing a slide of Barack Obama with a book in his hand, which turned out to be Walcott’s Collected Poems, 1948-1984. Then the poet read us Forty Acres, his new poem about Obama, commissioned by the Times of London: Out of the turmoil emerges one emblem, an engraving –/a young Negro at dawn in straw hat and overalls,/an emblem of impossible prophecy…

Asked for his reaction, Stoppard said that the poem “silenced” him–but, of course, it hadn’t, and he self-deprecatingly remarked that he could go on “speaking like a wind-up toy.” At one point he mentioned a recent New York Times article about the New York City Opera which pointed out that the Paris Opera’s budget is larger than that of the entire National Endowment for the Arts. Provocatively, he then suggested that the patronage of the rich American may “get the government off the hook.” This was power! This was culture! This was another ball dropped.

The next day, Stoppard was interiewed at BAM by David Remnick, editor of The New Yorker and author of Lenin’s Tomb, who may be the only editor in New York who hadn’t rushed out to read Isaiah Berlin justto prepare for The Coast of Utopia. Remnick actually out-Stopparded Stoppard with his wit and erudition, and the result was a chat that unlike its predecessor was fascinating, insightful, and over too soon. When Remnick said “For our last question…” Stoppard looked at his watch and looked truly disappointed.

The topic was Chekhov, but the conversation managed to get somewhere near…well, cultural power. Asked what niche his new version of The Cherry Orchard would fill, Stoppard said that directors like to have a new text in rehearsal: “Theatre is a storytelling art form–plays are palimpsests of maps on different scales.” He was “constantly looking for that elusive place where the natural utterance functions as a narrative utterance.”

Gracefully segueing from a consideration of Solzhenitsyn and Stalin to literary influence, Stoppard described his aesthetic response to newsprint and his early ambition to be a foreign correspondent and live a glamorous life. “It can be arranged,” Remnick murmured. For once Stoppard was speechless–briefly. Remnick added, “There’s a 10 p.m. to Kabul.” Then Stoppard recovered. “The St. Tropez kind of correspondent,” he replied.

Asked how working in America was different than at home, Stoppard admitted that he was less comfortable here, explaing that there was “more a sense of heavy pressure to succeed–perhaps there’s more shame in failing than there ought to be.” (Maybe that’s because they don’t publish the West End grosses every week.)

What next? Stoppard said that he’d had just about decided to start working on a screenplay for Arcadia that he would then direct when the BBC came up with the idea of adapting some novels from the nineteenth century and the Twenties–something he says that he really wants to do. Me, I hope it’s Waugh. I can’t imagine anybody channeling the glamorous war-correspondent author of A Handful of Dust better than Tom Stoppard.

TT: A traveling drama critic orders dinner for one

When Dad was on the road alone

And dined, alone, at night,

He wanted everything to be

Not passable, but right:

“A perfect baked potato

Demands the utmost care.

The only way to order steak

Is medium, not rare.”

When I was ten, I told myself:

How lucky to be grown,

To eat at fancy restaurants,

To do things on your own.

I sip my lukewarm Perrier,

A Trollope close to hand.

The waitress looks exactly like

That blonde in Freshman Band.

She smiles and serves the second course.

(Perhaps there’s too much sage?)

Suppressing shades of teenage lust,

I sigh and turn the page.

The rain descends, the Muzak purrs,

I chew my veal and think:

Just one more night and I’ll be home.

“Miss? Bring another drink.”

TT: Almanac

“If the explorer moves toward the risks of the formless and the unknown, the tourist moves toward the security of pure cliché. It is between these two poles that the traveler mediates.”

Paul Fussell, Abroad

TT: Size matters

The news that the Metropolitan Opera has decided to trim its budget by scrapping its revival of The Ghosts of Versailles set me to thinking about the problem of producing new operas that are conceived on a large scale. Such operas do get written–John Adams, for one, has had exceptionally good luck with the genre–but they tend not to get revived all that often. Conversely, a not-inconsiderable percentage of the operas written since 1945 that have had a healthy revival life are “chamber operas” like Benjamin Britten’s The Turn of the Screw and Gian Carlo Menotti’s The Medium that were specifically designed for performance by small companies.

The news that the Metropolitan Opera has decided to trim its budget by scrapping its revival of The Ghosts of Versailles set me to thinking about the problem of producing new operas that are conceived on a large scale. Such operas do get written–John Adams, for one, has had exceptionally good luck with the genre–but they tend not to get revived all that often. Conversely, a not-inconsiderable percentage of the operas written since 1945 that have had a healthy revival life are “chamber operas” like Benjamin Britten’s The Turn of the Screw and Gian Carlo Menotti’s The Medium that were specifically designed for performance by small companies.

The trouble with chamber operas is that they usually can’t be produced in a large auditorium, at least not very effectively. The Medium is an hour-long opera performed on a single set by a cast of five singers and an actor and accompanied by a fourteen-piece orchestra. You can make it work in a Broadway-sized theater–indeed, The Medium ran for seven months in the 1,100-seat Ethel Barrymore Theatre in 1947–but it feels a size or two too small when performed in most opera houses.

This isn’t a hard-and-fast rule. Mark Lamos’ staging of The Turn of the Screw was presented in 1996 by the New York City Opera in the 2,800-seat New York State Theater, and you never felt for a moment that the opera was dwarfed by the house. As I wrote in the New York Daily News two days after the opening:

Right from the start, this Turn of the Screw grabs you by the throat and doesn’t let go. Mark Lamos’ staging, surrealistically designed by John Conklin and lit with the flat, bright clarity of a nightmare by Robert M. Wierzel, emphasizes the horror-show aspects of the opera without descending into bathos or camp. Lamos has an uncanny knack for directing singers–I can’t remember the last time I saw better operatic acting.

Twelve years later, Lamos’ Turn of the Screw remains the most exciting production of that great opera that I’ve had the luck to see–but the fact remains that it was it was conceived for Glimmerglass Opera’s wonderfully intimate 910-seat Alice Busch Opera Theater in Cooperstown, New York, and I suspect that it packed an even bigger punch there than it did at Lincoln Center.

America’s opera houses range in size from the monstrous to the petite. The Lyric Opera of Chicago performs in the 4,300-seat Auditorium Theatre, while the Metropolitan Opera House holds 3,800 people. At the other end of the spectrum is New York’s Amato Opera House, which has 107 seats. Most American houses, however, fall somewhere in between these extremes. The Kennedy Center Opera House, home of the Washington National Opera, has 2,200 seats, 75 more than the Santa Fe Opera’s Crosby Theater, where The Letter, the opera that I’m writing with Paul Moravec, will be premiered next July.

America’s opera houses range in size from the monstrous to the petite. The Lyric Opera of Chicago performs in the 4,300-seat Auditorium Theatre, while the Metropolitan Opera House holds 3,800 people. At the other end of the spectrum is New York’s Amato Opera House, which has 107 seats. Most American houses, however, fall somewhere in between these extremes. The Kennedy Center Opera House, home of the Washington National Opera, has 2,200 seats, 75 more than the Santa Fe Opera’s Crosby Theater, where The Letter, the opera that I’m writing with Paul Moravec, will be premiered next July.

What sort of opera do you write for such large but not elephantine houses–and is it possible to write it in such a way that it can also be successfully staged in smaller theaters? As I mentioned the other day, the original proposal for The Letter that Paul and I made to the Santa Fe Opera was explicit on this point:

Our goal is to write an opera whose casting and scenic requirements are compatible with the needs of medium-sized regional houses but which is musically “big” enough to work just as well in large houses.

Hence The Letter, a ninety-minute-long opera with five major roles, two smaller but dramatically essential roles, and a chorus of a dozen men who also cover a number of minor parts. It calls for five simple sets that can be changed quickly and in full view of the audience: a living room, a lawyer’s office, a jail cell, the bar of the Singapore Club, and a courtroom. Paul is scoring The Letter for a full-sized pit orchestra, but he also plans to prepare a second version suitable for performance by a smaller group.

The Letter, in short, should be well within the means of most regional companies. At the same time, though, the opera’s emotional scale and musical gestures are anything but small. The next-to-last scene, for instance, takes place in the courtroom where Leslie Crosbie, the character played by Bette Davis in the 1940 film version of The Letter, is being tried for murder. It’s a churning, propulsive ensemble inspired by the “Tonight Quintet” from West Side Story, and even though there will only be sixteen singers on stage, it’s going to get loud.

The Letter, in short, should be well within the means of most regional companies. At the same time, though, the opera’s emotional scale and musical gestures are anything but small. The next-to-last scene, for instance, takes place in the courtroom where Leslie Crosbie, the character played by Bette Davis in the 1940 film version of The Letter, is being tried for murder. It’s a churning, propulsive ensemble inspired by the “Tonight Quintet” from West Side Story, and even though there will only be sixteen singers on stage, it’s going to get loud.

If I had to guess, I’d say that The Letter will be a bit too small for the Metropolitan Opera House, but it ought to fit quite nicely into the Crosby Theater–though the Met, lest we forget, has a long history of presentng such compact works as Mozart’s Così fan tutte, which calls for for six singers and a smallish chorus and orchestra, alongside grander-than-grand operas like Otello and Turandot. Might our not-so-little melodrama eventually turn up there as well, especially now that the Met’s management has become newly cost-conscious? I doubt it, but stranger things have happened…

UPDATE: Two friends wrote to point out what I knew perfectly well but somehow managed to forget, which is that the Chicago Lyric Opera performs not in the Auditorium Theatre but in the Civic Opera House, which has 3,600 seats, a couple of hundred fewer than the Metropolitan Opera House. Big, in other words, but not super-big.

My apologies.

TT: A package from home

If you read this posting and found it sobering, you might want to consider contributing to Operation Gratitude, which sends personalized “care packages” to American troops deployed overseas. Take a look at the Operation Gratitude mailbag and you’ll know what a difference these packages can make.

This letter caught my eye:

Hello from Afghanistan. I just want to say thank you very much for the care package. I received the package yesterday and I enjoyed it more than words can explain. I am not sure if the people back home understand fully the appreciation that we feel when we get these packages for home. It is very difficult to explain and I don’t think I would be able, even if I tried, so I will just say thank you again. God bless you all and take care, Sergeant Major D. J. C. US Army

He did just fine.

TT: Almanac

“The psychological principle is this: anyone can do any amount of work, provided it isn’t the work he is supposed to be doing at that moment.”

Robert Benchley, “How to Get Things Done”

TT: Karl Marx in a tutu

This was a two-musical week–I saw Billy Elliot on Broadway and Disney High School Musical at New Jersey’s Paper Mill Playhouse, and didn’t care for either show. Here’s an excerpt from my Wall Street Journal review.

* * *

Elton John, who fell flat on his face with “Lestat,” his last Broadway musical, is back in town with a show that promises to have a longer and considerably more profitable run. “Billy Elliot,” a stage version of the 2000 film about a coal miner’s son who longs to be a ballet dancer, opened in London three years ago and is still going strong. Small wonder, since “Billy Elliot,” seen from one point of view, has everything you could possibly want in a musical: It’s a Thatcher-bashing big-budget three-hour glamfest that makes tough-minded noises but ends up being a 20-hankie weeper.

The setting of “Billy Elliot” is the British miners’ strike of 1984-85, about which the average American playgoer knows absolutely nothing. This makes it possible for Lee Hall, who wrote the book and lyrics, to dish up a version that is–to put it very, very, very mildly–a trifle one-sided. In one of the fanciest numbers, a chorus of winsome miners’ children sings a festive holiday carol whose refrain goes like this: Merry Christmas Maggie Thatcher/We all celebrate today/Cause it’s one day closer to your death.

Against this black-and-white backdrop of class warfare, we meet young Billy, a motherless 11-year-old kid who falls in love with dance, struggles to persuade his homophobic family to send him to the Royal Ballet School and…but you can guess the rest, right? Even if you didn’t see the movie, you’d have to be pretty slow on the uptake not to see the happy ending lumbering down the pike, complete with a kick line of miners in tutus who’ve evidently gotten in touch with their inner Busby Berkeleys.

Musicals, of course, don’t have to be surprising to be good. What counts is craftsmanship, of which “Billy Elliot” has some, and emotional truth, of which it has none whatsoever….

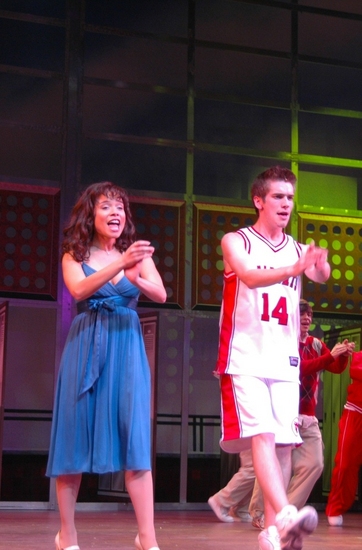

Two hundred fifty-five million people, I’m told, have seen the original “High School Musical” movie. Not being one of them, I can’t tell you how the stage version measures up, but Paper Mill’s production, directed by Mark S. Hoebee and choreographed by Denis Jones, is a slick and satisfying piece of work. Two of the performers, Sydney Morton and Stephanie Pam Roberts, are exceptional–I’ll be surprised if Ms. Morton, who plays Gabriella, the pretty math whiz, doesn’t make it to Broadway one of these days–and everyone else is both talented and likable. The sets and costumes are handsome, the pit band excellent.

Two hundred fifty-five million people, I’m told, have seen the original “High School Musical” movie. Not being one of them, I can’t tell you how the stage version measures up, but Paper Mill’s production, directed by Mark S. Hoebee and choreographed by Denis Jones, is a slick and satisfying piece of work. Two of the performers, Sydney Morton and Stephanie Pam Roberts, are exceptional–I’ll be surprised if Ms. Morton, who plays Gabriella, the pretty math whiz, doesn’t make it to Broadway one of these days–and everyone else is both talented and likable. The sets and costumes are handsome, the pit band excellent.

What about the musical itself? It is, not at all surprisingly, an innocuous confection that gives the impression of having been written by a committee on a computer. The book is a sexless Mickey-and-Judy-join-the-drama-club fable into which the high-minded folks at Disney have shoehorned far more than their usual quota of public-service announcements for tolerance. (In the small world of Disney, tolerance is the sole and only virtue.) The kiddie-rock score is the work of 13 different songwriters, none of whom shows any sign of being able to write a catchy tune or a clever lyric….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Watch my wsj.com video review of Billy Elliot here: