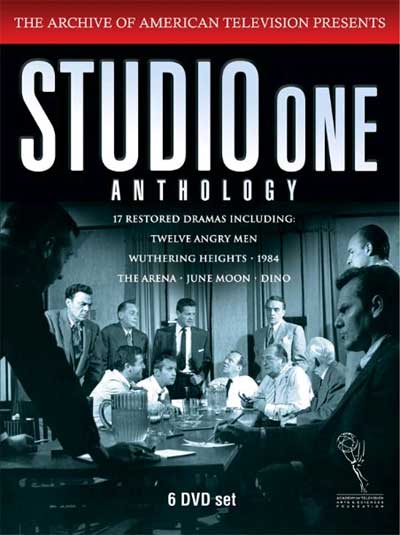

Like many another aging baby boomer, I’m fascinated by early television, and in particular by the live telecasts that dominated network TV from its inception at the end of the Forties to the introduction of videotape in the late Fifties. So when Koch Vision sent me a copy of Studio One Anthology, a six-DVD box set containing kinescopes of seventeen dramas that aired between 1948 and 1956 on Studio One, perhaps the best-remembered anthology drama series of the live-TV era, I immediately felt a “Sightings” column coming on.

Like many another aging baby boomer, I’m fascinated by early television, and in particular by the live telecasts that dominated network TV from its inception at the end of the Forties to the introduction of videotape in the late Fifties. So when Koch Vision sent me a copy of Studio One Anthology, a six-DVD box set containing kinescopes of seventeen dramas that aired between 1948 and 1956 on Studio One, perhaps the best-remembered anthology drama series of the live-TV era, I immediately felt a “Sightings” column coming on.

Studio One Anthology contains, among other interesting things, the original 1954 TV version of Reginald Rose’s Twelve Angry Men, which was later turned into a Hollywood film starring Henry Fonda and a stage version that was first performed on Broadway in 2004. I never cared for the movie and had mixed feelings about the play, but I was eager to see what Twelve Angry Men looked like in its original form.

How did it measure up to its better-known successors–and is Studio One as good as its still-formidable reputation? To find out, pick up a copy of Saturday’s Wall Street Journal and turn to my “Sightings” column.

UPDATE: Read the whole thing here.

Archives for November 2008

TT: Almanac

“When we imagine what it is like to be a languageless creature, we start, naturally, from our own experience, and most of what then springs to mind has to be adjusted (mainly downward). The sort of consciousness such animals enjoy is dramatically truncated, compared to ours. A bat, for instance, not only can’t wonder whether it’s Friday; it can’t even wonder whether it’s a bat; there is no role for wondering to play in its cognitive structure.”

Daniel Clement Dennett, Consciousness Explained

GALLERY

John Marin: Ten Masterworks in Watercolor (Meredith Ward, 44 E. 74, up through Dec. 20). Ten important works on paper by the pioneering American modernist whose virtuosity in the watercolor medium remains unrivaled. Some are from Marin’s estate, others from private collections, and most are familiar only to Marin specialists. A rare opportunity to view a great American painter at the peak of his powers (TT).

TT: So you want to see a show?

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

Warning: Broadway shows marked with an asterisk were sold out, or nearly so, last week.

BROADWAY:

• Alfred Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps (comedy, G, suitable for bright children, reviewed here)

• August: Osage County (drama, R, adult subject matter, reviewed here)

• Avenue Q (musical, R, adult subject matter and one show-stopping scene of puppet-on-puppet sex, reviewed here)

• Boeing-Boeing (comedy, PG-13, cartoonishly sexy, reviewed here)

• Equus (drama, R, nudity and adult subject matter, closes Feb. 8, reviewed here)

• Gypsy (musical, PG-13, adult subject matter, closes Mar. 1, reviewed here)

• The Little Mermaid (musical, G, entirely suitable for children, reviewed here)

• A Man for All Seasons (drama, G, too intellectually demanding for children of any age, closes Dec. 14, reviewed here)

• South Pacific * (musical, G/PG-13, some sexual content, brilliantly staged but unsuitable for viewers acutely allergic to preachiness, reviewed here)

OFF BROADWAY:

• The Fantasticks (musical, G, suitable for children capable of enjoying a love story, reviewed here)

CLOSING NEXT WEEK IN SUBURBAN CHICAGO:

• Picnic (drama, PG-13, adult themes, closes Nov. 30, reviewed here)

TT: Almanac

“We are always on stage, even when we are stabbed in earnest at the end.”

Georg Büchner, Danton’s Death (trans. Gerhard P. Knapp)

OGIC: Killing me softly

I’m really obsessed with Keats’s “To Autumn”; I think it’s a perfect and magical piece of writing, with effects that resonate and evolve for a lifetime. I got familiar with the poem in my first year of graduate school, when I took a memorable course called “Keats and Critique.” The course explored the premise–popular among the Victorians who installed him belatedly as a great English poet–that Keats was done in, in part, by his bad reviews. And it’s true that when they were bad, they were vicious.

When I reread this poem–or, as lately, recite it and write it out as outlets for its hold upon my ear and brain–I fend off impulses to thrust it upon innocent passers-by, pointing out its most bewitching features. I don’t so much have a reading of it as a set of things I notice in it, a collection that grows slowly over the years. Here are just a few of these amateur observations, truly off the top of my head; consider yourself one of those unsuspecting bystanders.

The first stanza describes an ample, apparently endless autumn bounty.

Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun;

Conspiring with him how to load and bless

With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run;

To bend with apples the moss’d cottage-trees,

And fill all fruit with ripeness to the core;

To swell the gourd, and plump the hazel shells

With a sweet kernel; to set budding more,

And still more, later flowers for the bees,

Until they think warm days will never cease,

For summer has o’er-brimmed their clammy cells.

Throughout the poem there’s a (deceptive) sense that time is suspended. In this stanza, that’s accomplished in large measure by the repeated use of infinitive verbs: “to load and bless”; “to bend”; “[to] fill”: “to swell”; “[to] plump”; “to set.” The last line, explaining how the bees are fooled, links this sense of time drawn out to the abundance described throughout the stanza. Tees bent under the weight of fruit, the filling, swelling, plumping, budding, overbrimming of nature–all of this burgeoning–is mimicked in the poem’s language, where phrases spill over the bounds of their lines and a gratuitous second instance of “more” in line nine performs the word’s own meaning. The stanza is literally fruitful: “fruit” appears three times in its 11 lines, including an instance as something that fills (vines) and one as something that is filled (with ripeness).

The next stanza switches gears, presenting autumn as an allegorical figure.

Who hath not seen thee oft amid thy store?

Sometimes whoever seeks abroad may find

Thee sitting careless on a granary floor,

Thy hair soft-lifted by the winnowing wind;

Or on a half-reap’d furrow, sound asleep,

Drows’d with the fume of poppies while thy hook

Spares the next swath and all its twined flowers:

And sometimes like a gleaner thou dost keep

Steady thy laden head across a brook;

Or by a cyder-press, with patient look,

Thou watchest the last oozings hours by hours.

Again, time is on hold. The personified Autumn is an indolent creature, “sitting careless” in a workplace, “sound asleep” in the fields, watching the press rather than operating it. Even in the most industrious of the four attitudes described here, she is only like a gleaner. The work of her hook, in her previous guise, is to “spare”; it’s at rest. All of this is in contrast with the busy industry of the first stanza, though the sense of time stood still persists. Until that last line, that is, when a sense of ending finally sets in–in the “last oozings,” significant both for the adjective’s meaning and for the noun’s sound, and in the invocation of hours. There’s also the gently diminishing length of the four views of Autumn offered here: they fill three lines, three lines, two, and two. (Note, though, they stop short of approaching zero.)

The third and last stanza masterfully dissolves into sounds, capturing a last, momentary stasis before winter sets in.

Where are the songs of spring? Ay, where are they?

Think not of them, thou hast thy music too,–

While barred clouds bloom the soft-dying day,

And touch the stubble-plains with rosy hue;

Then in a wailful choir the small gnats mourn

Among the river sallows, borne aloft

Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies;

And full-grown lambs loud bleat from hilly bourn;

Hedge-crickets sing; and now with treble soft,

The red-breast whistles from a garden-croft;

And gathering swallows twitter in the skies.

There are so many interesting things going on here. The use of “bloom” as a transitive verb; the singular, whistling red-breast set against the plural plains, gnats, sallows, lambs, crickets, swallows, and skies; the seemingly unnecessary designation of the gnats as “small.” Autumn’s music, it must be said, is a gentle, symphonic, glorious, consoling…dirge. “Soft-dying” describes not only the day but the season and the year as viewed through the prism of this poem, and by extension human life (it also provides a coda to the soft-lifting of stanza two). From its flirting with the notion of birth, through the use of the homophones “borne” and “bourn” (not to mention rhyming them with “mourn”), to the invocation of lambs on the threshold of adulthood and a wind that flits easily from death to life, it looks to the seasonal cycle for consolation for the life-cycle. It tries to touch mortality with rosy hue. It softens you up for the final blow, which takes place off the page–delivered, we imagine, softly.

P.S. By coincidence, Anecdotal Evidence also posts on Keats, death, and beauty today.

TT: Clive Barnes, R.I.P.

When I was a teenager and first became aware of criticism as a profession, Clive Barnes was one of its very biggest names. Born in 1927, Barnes had come to this country in 1965 to work for the New York Times. Right from the start, he was the kind of writer who got written about, in part because he had two arrows in his critical quiver: he covered dance and theater, and did so with self-evident relish. At some point it occurred to me that I, too, might want to write about more than one subject, and I have no doubt that Barnes’ example was part of what inspired me to do so.

When I was a teenager and first became aware of criticism as a profession, Clive Barnes was one of its very biggest names. Born in 1927, Barnes had come to this country in 1965 to work for the New York Times. Right from the start, he was the kind of writer who got written about, in part because he had two arrows in his critical quiver: he covered dance and theater, and did so with self-evident relish. At some point it occurred to me that I, too, might want to write about more than one subject, and I have no doubt that Barnes’ example was part of what inspired me to do so.

I discovered ballet in 1987 and started writing about it for The New Dance Review shortly thereafter. That was when I first recognized Barnes as a physical presence, sitting on the aisle of virtually every first night that I attended. Sixteen years later I became the drama critic of The Wall Street Journal and joined the New York Drama Critics’ Circle, of which Barnes and John Simon were the senior members. It seemed utterly improbable to me that I should be casting votes alongside men whose reviews I’d been reading for the better part of four decades, much less calling them by their first names. I found Clive to be perfectly friendly and collegial, but by then it was impossible for me to shed the diffidence of my long-lost youth and get to know him more than casually. To me he was Clive Barnes, and that was that.

Clive’s byline recently disappeared from the New York Post, to which he had moved in 1978, and the paper’s dance and drama reviews started carrying an ominous tagline: Clive Barnes is on leave. This morning a mutual friend passed the not-surprising word that he had died of liver cancer. Almost to the end, though, he clung to his aisle seat, and as late as two weeks ago he was still filing reviews that left no doubt of his undiminished appetite for ballet, the art that he loved most and knew best. That’s the best of all possible epitaphs for a long-lived critic.

UPDATE: The New York Times obituary is here.

The New York Post obituary is here.

TT: Snapshot

Sid Caesar and Nanette Fabray engage in a pantomime argument on a 1954 episode of Caesar’s Hour, accompanied by the first movement of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony:

(This is the latest in a weekly series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Wednesday.)