I review three shows in this week’s Wall Street Journal drama column. Two are on Broadway, All My Sons and To Be or Not to Be, and both are doubleplusungood. Not so the Cleveland Play House’s revival of Noises Off, which I liked enormously. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

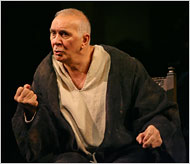

Everything that Arthur Miller was to become can be seen in embryo in “All My Sons,” his first hit, which ran for nine months on Broadway in 1947 and has now returned there in a revival graced–if that’s the word–by the presence of Katie Holmes. Earnest and hectoring, “All My Sons” is as much a secular sermon as a play, a school-of-Ibsen indictment of the moral emptiness of the American bourgeoisie, always a draw for guilt-wracked playgoers who enjoy being flagellated at $100 a pop. Unlike the plays that followed it, however, “All My Sons” is for the most part satisfyingly unpretentious, a next-to-no-nonsense wartime tragedy about a corrupt factory owner (John Lithgow) whose greed leads to the suicide of his soldier son, and it deserves better than this windy production, in which Simon McBurney commits first-degree directorial malpractice.

Mr. McBurney is the artistic director of Complicité, a British avant-garde theater troupe whose work I admire. Perhaps not surprisingly, he has used “All My Sons” as a vehicle for his multi-media prestidigitation: Newsreel-style rear projections, thunderous sound effects and spooky incidental music are seen and heard throughout the evening, while Tom Pye’s minimalist set looks as though it were designed for an opera by Philip Glass. But while this trickery might well have been impressive if deployed in the service of one of Complicité’s surreal spectacles, it has nothing whatsoever to do with the modest exercise in kitchen-sink naturalism that is “All My Sons,” and Miller’s script all but disappears under the weight of Mr. McBurney’s staging….

Mr. McBurney is the artistic director of Complicité, a British avant-garde theater troupe whose work I admire. Perhaps not surprisingly, he has used “All My Sons” as a vehicle for his multi-media prestidigitation: Newsreel-style rear projections, thunderous sound effects and spooky incidental music are seen and heard throughout the evening, while Tom Pye’s minimalist set looks as though it were designed for an opera by Philip Glass. But while this trickery might well have been impressive if deployed in the service of one of Complicité’s surreal spectacles, it has nothing whatsoever to do with the modest exercise in kitchen-sink naturalism that is “All My Sons,” and Miller’s script all but disappears under the weight of Mr. McBurney’s staging….

Like most of the pretty young screen things who have made Broadway debuts in recent seasons, Ms. Holmes is a creature of the camera who doesn’t know the first thing about stage acting. Anyone misguided enough to make her professional stage debut on Broadway opposite Mr. Lithgow and Ms. Wiest in an Arthur Miller play is, of course, asking for trouble, and Ms. Holmes gets it in spades….

Ernst Lubitsch never made a funnier movie than “To Be or Not to Be,” in which Jack Benny played a second-rate Polish actor who bamboozles the Nazis in spite of himself. Why, then, attempt to turn so well-made a work of cinematic art into a stage play? A musical, maybe, but Nick Whitby’s adaptation, which takes the script of the 1942 film and pumps it full of new punch lines and a semi-serious ending, makes no sense at all–not least because none of Mr. Whitby’s jokes is even slightly funny….

“Noises Off,” first seen on Broadway in 1983, consists of a rehearsal and two performances of “Nothing On,” a not-so-hot British sex comedy acted by a calamity-prone touring troupe. The gimmick of the show is that the set is turned around for the second act, allowing us to witness the disastrous backstage occurrences from the actors’ point of view. The result is a metafarce–a farce whose subject matter is farce itself. Neeedless to say, so complicated a conceit cannot possibly be made to work without pristinely immaculate craftsmanship, but “Noises Off” fills the bill. Once the nine doors of James Leonard Joy’s two-story set start slamming, the laughter starts swelling in a crescendo so protracted that it’s a wonder people don’t faint in the aisles from sheer exhaustion.

David H. Bell, the director of this production, is a specialist in musical comedy who doubles as a choreographer, which may help to explain the miraculous exactitude with which he has staged “Noises Off.” Every comic bomb goes off at the right split-second….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Watch my wsj.com video review here:

Archives for October 2008

TT: Almanac

“You critics are always writing about the meaning of music, the ethic, the Weltanschauung of the composer, and God knows what. The whole point of music is that it should sound well. Never mind what it signifies. Music should have wings and float and give delight.”

Sir Thomas Beecham (quoted in Neville Cardus, Autobiography

TT: So you want to see a show?

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

Warning: Broadway shows marked with an asterisk were sold out, or nearly so, last week.

BROADWAY:

• Alfred Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps (comedy, G, suitable for bright children, reviewed here)

• August: Osage County (drama, R, adult subject matter, reviewed here)

• Avenue Q (musical, R, adult subject matter and one show-stopping scene of puppet-on-puppet sex, reviewed here)

• Boeing-Boeing (comedy, PG-13, cartoonishly sexy, reviewed here)

• Equus (drama, R, nudity and adult subject matter, closes Feb. 8, reviewed here)

• Gypsy (musical, PG-13, adult subject matter, reviewed here)

• The Little Mermaid * (musical, G, entirely suitable for children, reviewed here)

• A Man for All Seasons (drama, G, too intellectually demanding for children of any age, extended through Dec. 14, reviewed here)

• A Man for All Seasons (drama, G, too intellectually demanding for children of any age, extended through Dec. 14, reviewed here)

• South Pacific * (musical, G/PG-13, some sexual content, brilliantly staged but unsuitable for viewers acutely allergic to preachiness, reviewed here)

OFF BROADWAY:

• The Fantasticks (musical, G, suitable for children capable of enjoying a love story, reviewed here)

CLOSING NEXT SATURDAY IN CHICAGO:

• R.U.R. (serious comedy, PG-13, adult themes, closes Oct. 25, reviewed here)

CLOSING NEXT SUNDAY OFF BROADWAY:

• Enter Laughing (musical, PG-13, full of sex jokes, closes Oct. 26, reviewed here)

TT: The second time around

I heard from a connoisseur of the art of Giorgio Morandi not long after I posted yesterday morning on the deficiencies of the Metropolitan Museum’s Morandi retrospective:

I heard from a connoisseur of the art of Giorgio Morandi not long after I posted yesterday morning on the deficiencies of the Metropolitan Museum’s Morandi retrospective:

Another time we can perhaps discuss the Met’s presentation. It is a much neglected but in my eyes crucial element to understanding Morandi’s paintings, generally speaking and also to reveal their contemporaneity. To me they have specificity that requires very close attention to how they are (1) framed, (2) grouped, (3) spaced within a room. For example, no one would ever dare to jam as many Robert Rymans in one room, let alone that room. Giacometti is another you would not dare doing this to–although MoMA has (oops!).

The results, as you say, were “educational,” but only in the sense of being able to see the paintings in person rather than in reproduction. Had the Met mounted them with space to spare in the large galleries, it would have been a true eye opener towards greater understanding of the monumentality of Morandi’s work–and a riveting pleasure at that.

I couldn’t agree more. Morandi’s paintings should not be jammed together, as they are at the Met. They need plenty of space to breathe and resonate. They also need silence, and so I went back to the Met at noon yesterday to take a second look at the show, which I had seen under unfavorable circumstances on Sunday afternoon. It was slightly less crowded but no less full of enthusiastic conversationalists. Next time I’ll try going earlier in the morning.

When you go–and you should, soon–I commend your special attention to the following items: 4, 17, 34, 44, 57, 64, 82, 86 (from the Phillips Collection), 105, 107, 111, 120, 121, and 125 (Morandi’s last painting).

TT: Almanac

“A comfortable house is a great source of happiness. It ranks immediately after health and a good conscience.”

Sydney Smith, letter, Sept. 29, 1843

TT: Never on Sunday

Mrs. T departed for Connecticut last Friday morning, and I promptly hurled myself into a frenzy of urban activity. It was a brilliant and balmy weekend in New York City, the best of all possible times to be out and about, and so I spent very little time at home. On Friday evening I saw To Be or Not to Be on Broadway. The next morning I went to the gym, dropped by Mr. JazzWax‘s apartment to listen to records, visited two art galleries, and returned to Broadway to see Katie Holmes make her stage debut in Arthur Miller’s All My Sons. On Sunday I took a brisk walk through Central Park, ending up at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where I spent an hour looking at paintings, then returned to the Upper West Side to dine at Good Enough to Eat, where I hadn’t eaten for weeks. Walking through the front door felt a little like coming home after a sea voyage.

Mrs. T departed for Connecticut last Friday morning, and I promptly hurled myself into a frenzy of urban activity. It was a brilliant and balmy weekend in New York City, the best of all possible times to be out and about, and so I spent very little time at home. On Friday evening I saw To Be or Not to Be on Broadway. The next morning I went to the gym, dropped by Mr. JazzWax‘s apartment to listen to records, visited two art galleries, and returned to Broadway to see Katie Holmes make her stage debut in Arthur Miller’s All My Sons. On Sunday I took a brisk walk through Central Park, ending up at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where I spent an hour looking at paintings, then returned to the Upper West Side to dine at Good Enough to Eat, where I hadn’t eaten for weeks. Walking through the front door felt a little like coming home after a sea voyage.

You’ve probably guessed that I spent a good-sized chunk of the weekend looking at the paintings, watercolors, and etchings of Giorgio Morandi, which are currently on display at the Met, Pace Master Prints, and Lucas Schoormans Gallery. My trip to the Met wasn’t quite as satisfying as I’d hoped, however, though not because of the show, which isn’t quite perfect–the choice of etchings is less than representative–but comes close enough to be unforgettable. The problem is that the curators of the show made the inexplicable and irreparable mistake of installing it in a high-traffic area that is mere steps away from the museum’s new downstairs cafeteria. As a result, “Giorgio Morandi, 1890-1964” is drawing large numbers of people who would rather talk than look at art, not a few of whom seem unaware that the use of a cellphone within five hundred yards of a Morandi still life would be punishable by death and/or dismemberment if I had anything to do with it.

You’ve probably guessed that I spent a good-sized chunk of the weekend looking at the paintings, watercolors, and etchings of Giorgio Morandi, which are currently on display at the Met, Pace Master Prints, and Lucas Schoormans Gallery. My trip to the Met wasn’t quite as satisfying as I’d hoped, however, though not because of the show, which isn’t quite perfect–the choice of etchings is less than representative–but comes close enough to be unforgettable. The problem is that the curators of the show made the inexplicable and irreparable mistake of installing it in a high-traffic area that is mere steps away from the museum’s new downstairs cafeteria. As a result, “Giorgio Morandi, 1890-1964” is drawing large numbers of people who would rather talk than look at art, not a few of whom seem unaware that the use of a cellphone within five hundred yards of a Morandi still life would be punishable by death and/or dismemberment if I had anything to do with it.

I’m sure, by the way, that I beamed benevolently at some of the very same people when I saw them in Central Park a few minutes earlier. Parks are supposed to be crowded on balmy Sunday afternoons, and I enjoyed every minute of my long walk from the West Side to the East Side. But a park is by definition open to all comers, a gathering place for the demos. An art museum is a trickier proposition. I know that I ought to want the Metropolitan Museum to be crowded seven days a week, that it should be a sign of cultural health for its galleries to be packed. I also know what it’s like to visit a museum that time and demography have passed by. In 2003 I paid a weekday visit to the Newark Museum and was shocked to find myself the only person in the galleries other than the guards. I would never want that to happen to the Met.

I’m sure, by the way, that I beamed benevolently at some of the very same people when I saw them in Central Park a few minutes earlier. Parks are supposed to be crowded on balmy Sunday afternoons, and I enjoyed every minute of my long walk from the West Side to the East Side. But a park is by definition open to all comers, a gathering place for the demos. An art museum is a trickier proposition. I know that I ought to want the Metropolitan Museum to be crowded seven days a week, that it should be a sign of cultural health for its galleries to be packed. I also know what it’s like to visit a museum that time and demography have passed by. In 2003 I paid a weekday visit to the Newark Museum and was shocked to find myself the only person in the galleries other than the guards. I would never want that to happen to the Met.

Alas, the experience of high art is democratic only in theory, never in practice, which is why there is something inherently contradictory, perhaps even deeply wrong, about seeing crowds at an exhibition of the paintings of Giorgio Morandi. Morandi is a difficult painter, one whose still lifes inevitably strike the casual viewer as both repetitive and plain. They require close, quiet attention in order to be appreciated. Giorgio Morandi: The Art of Silence is the apt title of a monograph about Morandi published a couple of years ago. It is inconceivable that anyone capable of talking in the presence of Morandi’s late watercolors, which are so concentrated and oblique as to border on outright abstraction, could possibly be appreciating them.

Alas, the experience of high art is democratic only in theory, never in practice, which is why there is something inherently contradictory, perhaps even deeply wrong, about seeing crowds at an exhibition of the paintings of Giorgio Morandi. Morandi is a difficult painter, one whose still lifes inevitably strike the casual viewer as both repetitive and plain. They require close, quiet attention in order to be appreciated. Giorgio Morandi: The Art of Silence is the apt title of a monograph about Morandi published a couple of years ago. It is inconceivable that anyone capable of talking in the presence of Morandi’s late watercolors, which are so concentrated and oblique as to border on outright abstraction, could possibly be appreciating them.

My Saturday visits to Pace Master Prints and Lucas Schoormans Gallery were a different story. I spent a half-hour looking at the two dozen etchings on display at Pace Master Prints, and throughout that time I was the only person in the gallery devoted to Morandi. I was glad to be alone–but troubled, too, by the fact that no one else in New York City was there. Morandi, after all, was one of the greatest printmakers of the twentieth century, a master of his infinitely subtle medium, and the Pace show is a once-in-a-lifetime experience, an indispensable pendant to the Met retrospective. How is it possible that so important an exhibition should have drawn only a single viewer at midday on a Saturday in October? Be careful what you ask for, I thought as I left the gallery.

My Saturday visits to Pace Master Prints and Lucas Schoormans Gallery were a different story. I spent a half-hour looking at the two dozen etchings on display at Pace Master Prints, and throughout that time I was the only person in the gallery devoted to Morandi. I was glad to be alone–but troubled, too, by the fact that no one else in New York City was there. Morandi, after all, was one of the greatest printmakers of the twentieth century, a master of his infinitely subtle medium, and the Pace show is a once-in-a-lifetime experience, an indispensable pendant to the Met retrospective. How is it possible that so important an exhibition should have drawn only a single viewer at midday on a Saturday in October? Be careful what you ask for, I thought as I left the gallery.

Things were different in yet another, more benign way when I arrived at Lucas Schoormans Gallery, whose Morandi show seems to me to be just about perfect. Instead of a hundred paintings and works on paper, there were a couple of dozen carefully chosen pieces on display. Instead of a clamorous horde of visitors–or none–there were six or seven people whose rapt, uncasual silence spoke for itself. Not for a moment did I doubt that they were there for the right reasons. Yet they had passed no test to be admitted: Lucas Schoormans Gallery, like Central Park, is open to all comers, not just to wealthy collectors or accredited connoisseurs. To partake of its offerings is, in the truest and best sense of the word, a democratic experience.

As for the Met, it is…well, the Met. While no great museum gets everything right, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, like the Phillips Collection, comes far closer than most. I am blessed to be within comfortable walking distance of its front door, and I expect to go back to see its Morandi exhibition several more times–but never again on a Sunday afternoon. It is possible to believe in the necessity of democracy without feeling the need to idealize it.

* * *

Lucas Schoormans Gallery’s “Giorgio Morandi: Paintings and Works on Paper” and Pace Master Prints’ “The Etchings of Giorgio Morandi” both close on Saturday. For more information, go here and here.

“Giorgio Morandi, 1890-1964” is up at the Met through December 14.

TT: Snapshot

Excerpts from the 1997 premiere of Paul Taylor’s Piazzolla Caldera, performed by the Paul Taylor Dance Company:

(This is the latest in a weekly series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Wednesday.)

TT: Almanac

“Great music is that which penetrates the ear with facility and leaves the memory with difficulty. Magical music never leaves the memory.”

Sir Thomas Beecham (quoted in the Sunday Times of London, Sept. 16, 1962)