Mrs. T and I are departing this afternoon for a brief, well-deserved holiday at Ecce Bed and Breakfast, the Catskills inn where we honeymooned a year ago. Our deflector shields will be set to maximum until Sunday, when we return to New York with what I expect to be the utmost reluctance. You’ll find the usual almanac entries and theater-related postings in this space, but if you need anything other than that between now and then, ask somebody else.

Mrs. T and I are departing this afternoon for a brief, well-deserved holiday at Ecce Bed and Breakfast, the Catskills inn where we honeymooned a year ago. Our deflector shields will be set to maximum until Sunday, when we return to New York with what I expect to be the utmost reluctance. You’ll find the usual almanac entries and theater-related postings in this space, but if you need anything other than that between now and then, ask somebody else.

Later.

Archives for October 2008

TT: Almanac

“Unlike any other visual image, a photograph is not a rendering, an imitation or an interpretation of its subject, but actually a trace of it. No painting or drawing, however naturalist, belongs to its subject in the way that a photograph does.”

John Berger, About Looking

TT: Adventures in copyright

One of the minor pleasures of writing a biography is picking the photographs that will be used to illustrate it–so long as you can get permission to reproduce them. When you can’t, it’s pure hell.

One of the minor pleasures of writing a biography is picking the photographs that will be used to illustrate it–so long as you can get permission to reproduce them. When you can’t, it’s pure hell.

In addition to looking through some two thousand photos of Louis Armstrong at the Armstrong Archives, I spent several days trolling the Web for images, mostly in vain, since just about everything I found was over-familiar and/or unusable. I did, however, run across one spectacular shot of Armstrong and the All Stars on stage in Amsterdam in 1955, and no sooner did I find it on a Web-based photo album than I knew I wanted to include it in A Cluster of Sunlight: The Life of Louis Armstrong. I’ve seen hundreds of pictures of Armstrong in performance, but I can’t think of one that does a better job of suggesting the atmosphere of a jazz concert.

On top of that, this particular photo is of what I believe to have been Armstrong’s best working group, the one that featured Edmond Hall on clarinet, Trummy Young on trombone, and Billy Kyle on piano. Armstrong, as it happens, felt exactly the same way. As he said in a little-known 1956 interview quoted in A Cluster of Sunlight:

Oh yeah, that first group of All Stars [i.e., the one that included Barney Bigard on clarinet, Sid Catlett on drums, Earl Hines on piano, and Jack Teagarden on trombone] was a good one all right, but I think the group I have now is the best of ’em all. It seems to me this band gets more appreciation now than the other All Stars. Some of the other Stars got so they was prima donnas and didn’t want to play with the other fellows. They wouldn’t play as a team but was like a basket ball side with everybody trying to make the basket. They was great musicians, but after a while they played as if their heart ain’t in what they was doin’. A fella would take a solo but no-one would play him no attention–just gaze here, look around there. And the audience would see things like that–I don’t praise that kind of work y’ know….

The All Stars now ain’t like that and the audience appreciate the spirit in the band. As musicians they ain’t any better, but a lot of people say these boys seem like they’re real glad to be up there swingin’ with me.

Here is that same band playing “Muskrat Ramble” on TV in 1958:

Clearly, then, I had to include that image in my book. There was only one catch, but it was a huge one: the Web album didn’t include the photographer’s name or e-mail address. So what did I do? Simple: I told Ariel Davis, my trusty research assistant, to track the man down. It took her a couple of weeks to oblige, but she finally brought home the bacon.

Much to my surprise, it turned out that Joel Elkins, who shot what Ariel and I had taken by then to calling the Mystery Photo, knew who I was. “It’s a pleasure to be associated with a book about the great Louis Armstrong written by someone such as yourself,” he wrote. Elkins charged a token fee for permission to reprint his wonderful picture in A Cluster of Sunlight, asking only that we send him a signed copy of the book when it comes out next year. I can’t wait to oblige.

No, it’s not always that easy….

TT: Almanac

“We also have to learn to forget music. Otherwise we become addicted to the past.”

Keith Jarrett (quoted in The Wall Street Journal, Oct. 11, 2008)

TT: In one piece

I’m up in Connecticut with Mrs. T, writing captions for the thirty-odd photographs that will be reproduced in A Cluster of Sunlight: The Life of Louis Armstrong, about which more later in the week. I was, alas, out of town when the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra gave the premiere of Paul Moravec‘s Brandenburg Gate at Carnegie Hall last Thursday night, but the composer was on hand to take a well-deserved bow. When not busy composing operas, Paul also writes instrumental music of tremendous distinction and individuality, and Brandenburg Gate, an homage to Bach’s Brandenburg Concerti, is one of his very best pieces. He called me in Connecticut on Friday morning to report that it was a hit, which didn’t surprise me in the least.

I’m up in Connecticut with Mrs. T, writing captions for the thirty-odd photographs that will be reproduced in A Cluster of Sunlight: The Life of Louis Armstrong, about which more later in the week. I was, alas, out of town when the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra gave the premiere of Paul Moravec‘s Brandenburg Gate at Carnegie Hall last Thursday night, but the composer was on hand to take a well-deserved bow. When not busy composing operas, Paul also writes instrumental music of tremendous distinction and individuality, and Brandenburg Gate, an homage to Bach’s Brandenburg Concerti, is one of his very best pieces. He called me in Connecticut on Friday morning to report that it was a hit, which didn’t surprise me in the least.

WNYC broadcast the concert live in New York and has since archived the program on its Web site. You can listen to it, as I did, by going here. The program also includes Haydn’s “Fire” Symphony, Jacques Ibert’s Hommage à Mozart, and the Saint-Saëns G Minor Piano Concerto, performed by Jean-Yves Thibaudet. To listen to Brandenburg Gate, skip forward to the thirty-minute mark in the playback. The performance is followed by an interview with Paul that was taped earlier in the day.

The announcers made public something that I’ve been keeping more or less under wraps until now, which is that Paul suffered a mild stroke in August. I’m sure I don’t need to tell you how scary that was, but the stroke, as you’ll hear when you listen to Paul talking about Brandenburg Gate, had no effect whatsoever on his mental processes (except that his e-mails were full of misspelled words for a week or so!). I’m delighted to say that he’s been spending the past few weeks orchestrating The Letter, which is, like A Cluster of Sunlight, moving steadily toward the finish line.

If you’d like to celebrate with us, check out Brandenburg Gate. I think you’ll like what you hear.

TT: Almanac

“Politics in a literary work is like a gun shot in the middle of a concert, something vulgar, and however, something which is impossible to ignore.”

Stendhal, The Charterhouse of Parma (trans. Jeri King)

TT: Neal Hefti and Dave McKenna, R.I.P.

Two more jazz masters have passed on. Neal Hefti was best known to the public for composing the Batman and Odd Couple themes, but among musicians it was his smoothly swinging work for Count Basie that made him legendary, in the process helping to update and redefine the language of postwar big-band arranging. The Atomic Mr. Basie, their best-known collaboration, contained “Li’l Darlin’,” the slower-than-slow ballad for which Hefti will always be remembered. Marc Myers’ obituary deftly summarizes his innumerable other musical achievements and offers a well-chosen list of recommended recordings. I especially like “The Good Earth,” the oft-reissued 1945 Woody Herman flagwaver that is one of my all-time favorite big-band recordings.

Dave McKenna was best known for his unaccompanied piano solos, whose propulsive left-hand walking-bass lines rendered sidemen superfluous. He was also a consummately sensitive balladeer, and Solo Piano, recorded for Chiaroscuro in 1972, includes a version of Leonard Bernstein’s “Lucky to Be Me” that shows him at his most tender. (You can download it from iTunes.)

Dave McKenna was best known for his unaccompanied piano solos, whose propulsive left-hand walking-bass lines rendered sidemen superfluous. He was also a consummately sensitive balladeer, and Solo Piano, recorded for Chiaroscuro in 1972, includes a version of Leonard Bernstein’s “Lucky to Be Me” that shows him at his most tender. (You can download it from iTunes.)

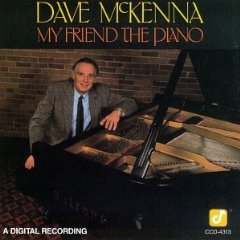

McKenna recorded frequently before illness forced him into retirement, but not nearly enough of his albums remain in print. I hope Concord will hasten to reissue My Friend the Piano, for me his most satisfying record. Used copies are easy to find, and I suggest that you order one, listen to “Baby, Baby All the Time,” and mourn the passing of an artist.

* * *

“Li’l Darlin’,” “The Good Earth,” and “Lucky to Be Me” can all be downloaded from iTunes.

Hefti’s New York Times obituary is here. McKenna’s is here.

Doug Ramsey writes well about Hefti and McKenna here and here.

Here’s an appropriately elegiac McKenna medley of Leonard Bernstein’s “Some Other Time” and Johnny Mandel’s “A Time for Love”:

MUSEUM

Giorgio Morandi, 1890-1964 (Metropolitan Museum, 1000 Fifth Ave., up through Dec. 14). It’s too crowded, too noisy, and poorly hung, but the Met’s Morandi exhibition, the first ever to come to the United States, is still a major event, a retrospective of one hundred and ten paintings and works on paper by one of the greatest and least sufficiently appreciated still-life painters of the twentieth century. Unless you take the trouble to go to Bologna’s Museo Morandi, it’s unlikely that you’ll ever get another chance to see this many Morandis at one time, so pick an off hour, pack a set of earplugs, and dive in (TT).