I’ve been reading Thomas A. Heinz’s Frank Lloyd Wright Field Guide, a book that describes every surviving building designed by Wright, tells you how to get to them, and assigns each one a five-star rating. The Field Guide also includes a brief discussion of the relative accessibility of each building. In most cases it’s a single sentence, usually either “The house can be seen from the street” or “The house cannot be seen from the street.” In certain cases, however, Heinz goes a bit further, and on occasion he really lets himself ago.

Some of his entries speak of bitter disappointment:

• “Visible from street and backyard but little to see” (Charles L. Manson House, Wausau, Wisconsin).

• “The station can be seen at all times and in all conditions. However, there is little to recommend a trip so far north unless visiting Duluth or the Boundary Waters” (Lindholm Service Station, Cloquet, Minnesota).

• “The front of the house is screened by evergreen trees. One can see only glimpses of the building, making photography of the subject frustrating” (Frank J. Baker House, Wilmette, Illinois).

Others hint at acute embarrassment:

• “The house is set well back on the site and cannot be seen from the street. Walking down the drive is not a good idea as it would disturb the occupants” (Carlton D. Wall House, Plymouth, Michigan).

• “The house can only be approached via the long driveway and by the time the house becomes visible one is nearly at the front door” (Duey Wright House, Wausau, Wisconsin).

I bet Mr. Heinz had some ‘splainin’ to do that day.

Like all Wright devotees, Thomas Heinz is a determined and tenacious fellow who will go to considerable trouble to see whatever there is to see:

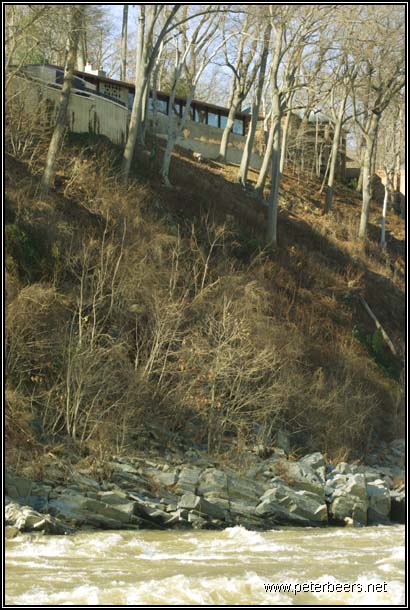

• “The house is over a small hill on the river slope. Only the garage doors can be seen from the roadside. The front of the house can be seen from across the river and the filtration plant. A fence with a gate obscures the house” (Luis Marden House, McLean, Virginia).

• “The house is over a small hill on the river slope. Only the garage doors can be seen from the roadside. The front of the house can be seen from across the river and the filtration plant. A fence with a gate obscures the house” (Luis Marden House, McLean, Virginia).

On occasion, though, he seems to have gotten himself into hot water. Some of the latter entries are devastatingly succinct:

• “Not visible. Beware of the dogs” (Maurice Greenberg House, Dousman, Wisconsin).

Others supply a proliferation of alarming detail:

• “The house is very difficult to see in both summer and winter because of the profusion of small trees and shrubs. There is an electric eye across the driveway that alerts the occupants to anyone approaching the house” (John O. Carr House, Glenview, Illinois).

• “The house is set almost a mile back from the public road, behind several gates and fences, and is extremely difficult to locate. It is still a private home and is not worth pursuing unless invited” (Amy Alpaugh Studio, Northport, Michigan).

• “The house cannot be seen from the street. There are barbed wire fences and dogs for the cattle and the occasional trespasser” (Arnold Friedman House, Pecos, New Mexico).

• “The compound is not accessible because of the narrow private road and ferocious animals kept by the owners. Unless invited, it would be better to avoid this house” (Donald Lovness House and Cottage, Stillwater, Minnesota).

One entry is so rich in implication as to suggest an unwritten short story:

• “The island is approachable only by boat. The island is guarded by dogs and a gate prevents getting past the dock. Only a small portion of the building can be seen from the water. The trained dogs are ever-present and have been known to chase passing boats” (A.K. Chahroudi Cottage, Mahopac, New York).

Here’s my favorite piece of cautionary advice:

• “Only a small portion of the top floor can be seen across the concrete court. The house can be seen from Highway 9 above the waterworks” (Frank Bott House, Kansas City, Missouri).

Talk about nostalgia! I used to go parking in the hills above the Kansas City Waterworks, some thirty-odd years ago. I don’t remember looking for any Frank Lloyd Wright houses, though….

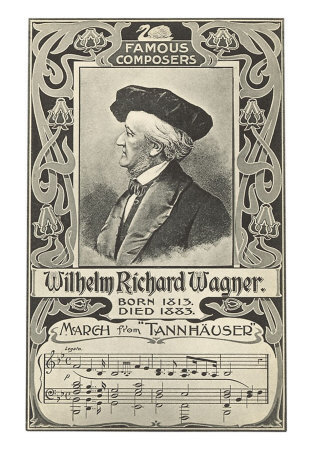

When Opera News asked me to review performances at the Met. I happily agreed, with a single caveat: “Please don’t ask me to cover Wagner.” And I never have. Nor do I review Wagner performances in the New York Daily News, for which I cover classical music and dance. I got caught a couple of years ago, when the New York Philharmonic opened its season with a Wagner-Strauss bill featuring Jessye Norman–there was no way I could wiggle out of that one–but otherwise, I have yet to write a word for either publication on the heated subject of the Beast of Bayreuth.

When Opera News asked me to review performances at the Met. I happily agreed, with a single caveat: “Please don’t ask me to cover Wagner.” And I never have. Nor do I review Wagner performances in the New York Daily News, for which I cover classical music and dance. I got caught a couple of years ago, when the New York Philharmonic opened its season with a Wagner-Strauss bill featuring Jessye Norman–there was no way I could wiggle out of that one–but otherwise, I have yet to write a word for either publication on the heated subject of the Beast of Bayreuth.