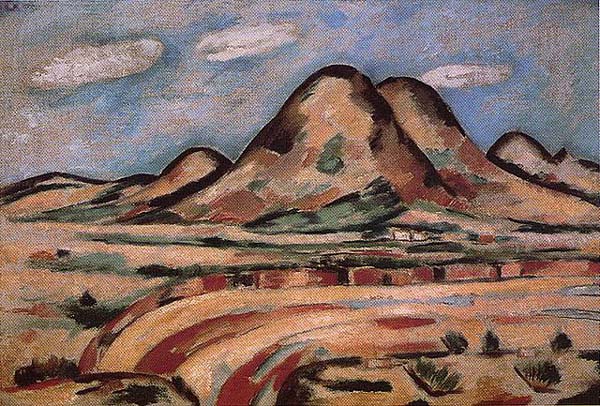

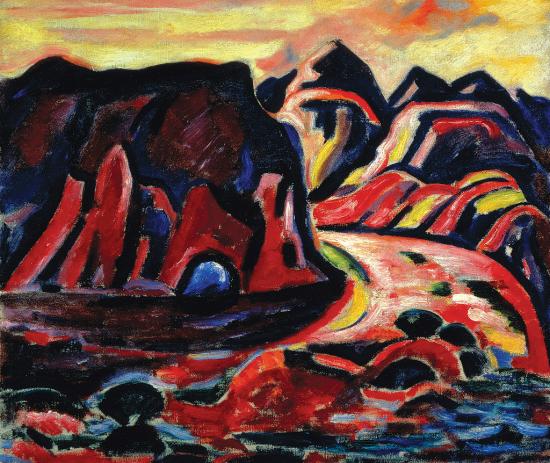

Richard Diebenkorn wasn’t the only modern American painter to have been stirred by the New Mexico landscape. It hit Marsden Hartley just as hard. “I want to paint the livingness of appearances,” Hartley said. He did just that when he came to Santa Fe in 1918, often to unforgettable effect.

Richard Diebenkorn wasn’t the only modern American painter to have been stirred by the New Mexico landscape. It hit Marsden Hartley just as hard. “I want to paint the livingness of appearances,” Hartley said. He did just that when he came to Santa Fe in 1918, often to unforgettable effect.

I can’t help but wonder what Hartley, who died in 1943, would have thought of the Santa Fe Opera‘s mesa-top theater, which opened its doors a decade ago. As eye-catching as it is, the Crosby Theater doesn’t stand out from the surrounding countryside so much as it blends into its complex contours. The open-air theater was oriented on the mesa in such a way as to allow directors and designers to use the desert sunset as a natural backdrop to the company’s productions, and the famously mercurial local weather–thunderstorms can blow up without warning–has been known to add an extra touch of drama.

The sensitivity with which the Crosby Theater was integrated into the Santa Fe landscape both reassured me and helped to teach me a lesson. How can the librettist and composer of a new opera, even one as action-packed as The Letter, hope to compete with thunderstorms and mountain ranges? As I watched the Santa Fe Opera perform The Marriage of Figaro, Falstaff, and Billy Budd, it occurred to me that opera is capable of “competing” on even terms with the most awe-inspiring of natural spectacles, since its subject matter–the passions of man–is no less inherently awesome.

The sensitivity with which the Crosby Theater was integrated into the Santa Fe landscape both reassured me and helped to teach me a lesson. How can the librettist and composer of a new opera, even one as action-packed as The Letter, hope to compete with thunderstorms and mountain ranges? As I watched the Santa Fe Opera perform The Marriage of Figaro, Falstaff, and Billy Budd, it occurred to me that opera is capable of “competing” on even terms with the most awe-inspiring of natural spectacles, since its subject matter–the passions of man–is no less inherently awesome.

Taking his cue from the fact that Paul Moravec and I have lately taken to calling The Letter an “opera noir,” Mark Tiarks, the Santa Fe Opera’s head of planning and marketing, wrote the following blurb for this year’s souvenir program:

Special delivery from composer Paul Moravec and librettist Terry Teachout: a hard-boiled dame cooks up her own little Singapore fling. Her double-crossing lover gets a lethal dose of lead as a lovely parting gift. Her sap of a husband helps her get away with murder. Almost…

Opera’s classic ingredients–lust, adultery, and revenge–are dished up noir style in this world premiere production. The Letter will be conducted by Patrick Summers and staged by Jonathan Kent, with scenery by Hildegard Bechtler and costumes by Tom Ford. Patricia Racette stars as the venomous Leslie Crosbie, Anthony Michaels-Moore plays her husband, and James Maddalena is their ethically challenged lawyer.

That’s a knowing and clever school-of-Chandler pastiche, and I was pleased to see it on the poster announcing the Santa Fe Opera’s 2009 season. On the other hand, I wouldn’t want anyone to get the idea that The Letter is, in the oft-quoted phrase with which Joseph Kerman amusingly (and wrongly) dismissed Tosca, a “shabby little shocker.” Paul and I have gone to considerable trouble to heighten the emotional climate of the play by Somerset Maugham on which our opera is based, in the process turning it from a neatly turned thriller into a full-fledged piece of lyric theater. Our characters, unlike Maugham’s, are concerned not just with their own desires but with the state of their souls.

In the words of Howard Joyce, the troubled lawyer in The Letter who’ll be played by Jim Maddalena:

I’ve lost my way in the jungle,

A way I knew when I was young,

When I thought I knew the truth.

But what is truth?

What is right?

What is love?

And where, where is the light?

None of Maugham’s characters asks such questions of himself, at least not out loud. In our version of The Letter, by contrast, they are the heart of the matter, and there is nothing shabby or small about them. We are never bigger than when we grapple, however vainly, with the ultimate mysteries, of which none is more profound–or impenetrable–than the mystery of love.

Would that I were a poet or a philosopher, but I’m only a critic! Still, I like to think that the powerful and ennobling music to which Paul set my simple words has made them worthy to be sung in a place like the Crosby Theater. If Maugham’s play were to be performed there, by contrast, it would probably seem very small indeed, just as its cynical characters would be dwarfed by their physical surroundings. That’s the difference between a well-made play and a work of lyric theater: one is about men, the other about man.

Would that I were a poet or a philosopher, but I’m only a critic! Still, I like to think that the powerful and ennobling music to which Paul set my simple words has made them worthy to be sung in a place like the Crosby Theater. If Maugham’s play were to be performed there, by contrast, it would probably seem very small indeed, just as its cynical characters would be dwarfed by their physical surroundings. That’s the difference between a well-made play and a work of lyric theater: one is about men, the other about man.

I am, of course, claiming a lot for Paul’s music, but I do so unhesitatingly: I believe without reservation in his great gifts. He’s not so sure. “Am I really ready to play in this league?” he asked me at the intermission of Billy Budd, and he meant it.

“You’d better believe it, pal,” I replied, and I meant it, too.

Mind you, I sympathized with Paul’s qualms. Not only is Budd one of the half-dozen best operas of the twentieth century, but The Marriage of Figaro and Falstaff are very possibly the two greatest operas ever written. Next summer The Letter will be sharing the stage with Don Giovanni and La Traviata, both of which are strong contenders for the same top honors. Britten, Mozart, and Verdi at their best–or even their second-best–are hard acts to follow, and only a halfwit would feel other than anxious at the thought of seeing his first opera premiered under such daunting circumstances.

Yet that didn’t stop us from writing The Letter, nor should it have done so. Whatever else we are or aren’t, Paul and I are honest craftsmen. We’ve done our best to make The Letter good, and we have no doubt that the Santa Fe Opera will do its best to make us look good. The company has already put together the best of all possible casts and production teams, starting with Patricia Racette, who was our first and only choice to create the role of Leslie Crosbie, the desperate anti-heroine of The Letter. I’ve admired Pat from afar ever since I reviewed her first Violetta at the Metropolitan Opera for the New York Daily News a decade ago. Now, much to my surprise, I’m working with her, and the experience is even more gratifying than I’d imagined it would be.

Yet that didn’t stop us from writing The Letter, nor should it have done so. Whatever else we are or aren’t, Paul and I are honest craftsmen. We’ve done our best to make The Letter good, and we have no doubt that the Santa Fe Opera will do its best to make us look good. The company has already put together the best of all possible casts and production teams, starting with Patricia Racette, who was our first and only choice to create the role of Leslie Crosbie, the desperate anti-heroine of The Letter. I’ve admired Pat from afar ever since I reviewed her first Violetta at the Metropolitan Opera for the New York Daily News a decade ago. Now, much to my surprise, I’m working with her, and the experience is even more gratifying than I’d imagined it would be.

With Pat, Jim, and Anthony on stage, Jonathan at the helm, and Hildegard and Tom designing the set and costumes, I think it’s fair to expect that the premiere of The Letter will be worth seeing and hearing. That’s as far as I’m prepared to go–but it’s far enough for me.

(Second of two parts)