Mrs. T and I spent last Tuesday and Wednesday in Jaffrey, New Hampshire, where we visited the grave of Willa Cather, whom I wrote about in the Teachout Reader and who has been much on my mind lately. Cather was a frequent visitor to Jaffrey–she wrote most of My Ántonia there–and in 1947 she was laid to rest in the Old Burying Ground, a cemetery located in back of the Meeting House, a steeple-topped church-like building that was raised by the citizens of Jaffrey in 1775.

I’m not in the habit of going to the gravesites of famous people, though I did make a point of seeking out H.L. Mencken’s grave when I was writing his biography and, a few years later, stopped by the resting place of Justice Holmes during a visit to Arlington National Cemetery. (I haven’t yet gone to the cemetery in Flushing where Louis Armstrong is buried, but I plan to do so as soon as I get back to New York in September.) This particular pilgrimage, however, seemed right, for the Old Burying Ground is just up the road from the 150-year-old inn where Mrs. T and I were staying, and it also happened that we were in town to see a production of a play whose last act is set in a New Hampshire cemetery.

The Old Burying Ground is shady, quiet, and full of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century tombstones, some worn almost smooth and others as legible as on the day they were carved. A fair number of Revolutionary War veterans are buried there, and their graves are marked with small flags. It’s not a spot that ordinary tourists seek out, nor does Cather’s grave appear to draw many visitors. Her headstone, which is at the southeastern corner of the cemetery, is moderately large, elegantly carved, and bears an inscription from My Ántonia: “…that is happiness; to be dissolved into something complete and great.” Immediately to the right of the stone, which is ringed by bright-colored impatiens, is a small, almost self-consciously discreet plaque that marks the grave of Edith Lewis, Cather’s companion, who outlived her by a quarter-century.

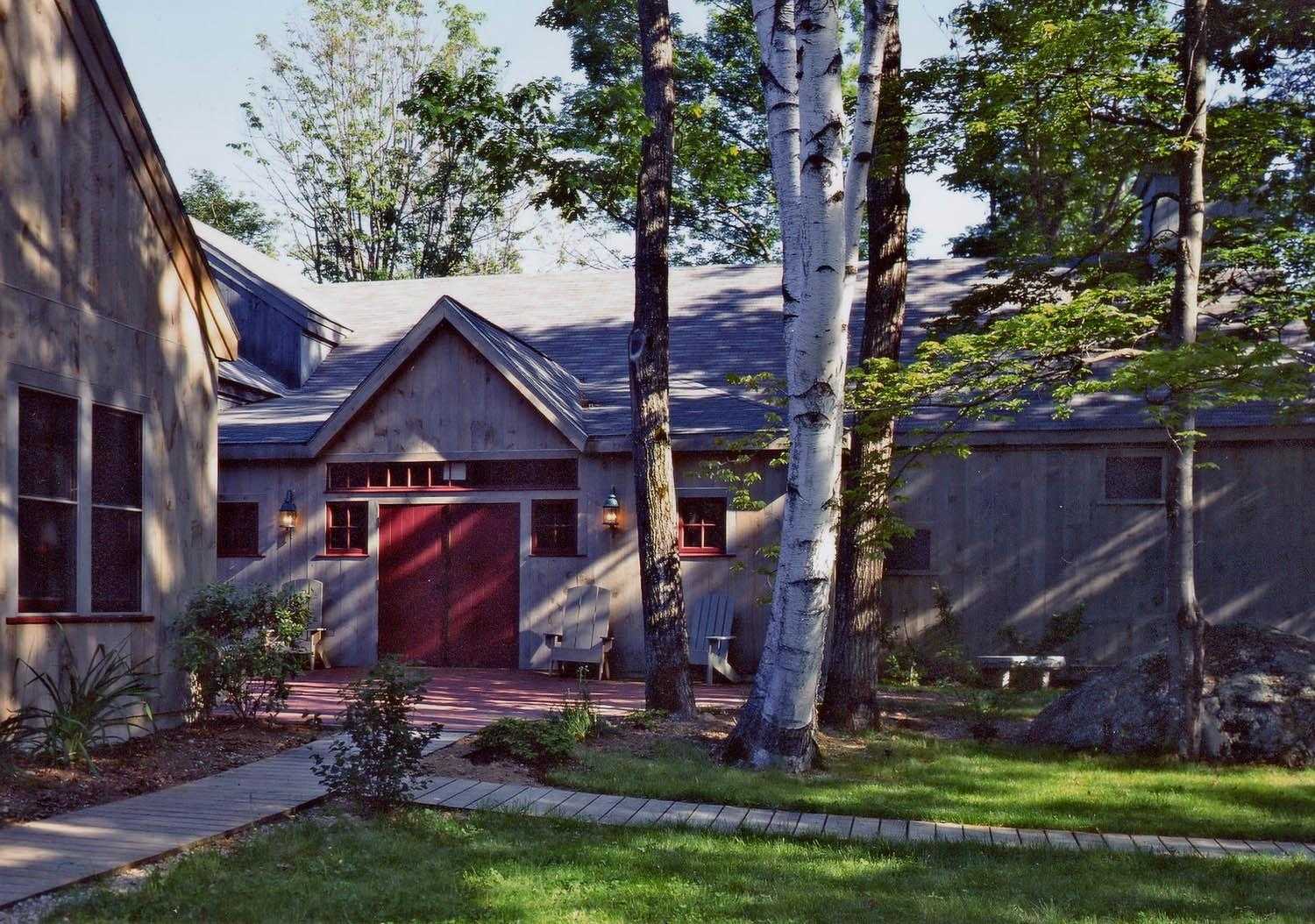

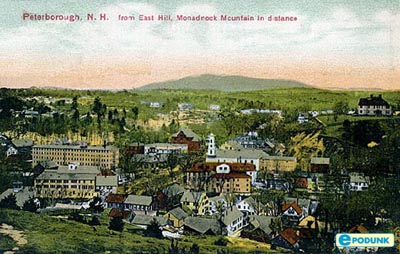

A few hours after departing the Old Burying Ground, Mrs. T and I drove to nearby Peterborough to see the Peterborough Players perform Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, a play that Cather admired greatly. Not long after seeing it on Broadway in 1938, she sent Wilder a letter telling him that Our Town was “the loveliest thing that has been produced in this country in a long, long time–and the truest.” Two years later the Peterborough Players became the first summer theater company ever to perform Our Town, and Wilder himself supervised the staging. He had written much of the play at the MacDowell Colony, which is only a couple of miles away from the converted barn where the Peterborough Players perform, and it is generally thought that he used the small town of Peterborough (pop. 5,883) as a model for Grover’s Corners, the imaginary hamlet (pop. 2,642) in which Our Town is set.

A few hours after departing the Old Burying Ground, Mrs. T and I drove to nearby Peterborough to see the Peterborough Players perform Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, a play that Cather admired greatly. Not long after seeing it on Broadway in 1938, she sent Wilder a letter telling him that Our Town was “the loveliest thing that has been produced in this country in a long, long time–and the truest.” Two years later the Peterborough Players became the first summer theater company ever to perform Our Town, and Wilder himself supervised the staging. He had written much of the play at the MacDowell Colony, which is only a couple of miles away from the converted barn where the Peterborough Players perform, and it is generally thought that he used the small town of Peterborough (pop. 5,883) as a model for Grover’s Corners, the imaginary hamlet (pop. 2,642) in which Our Town is set.

The role of the Stage Manager is being played this summer by James Whitmore, who is eighty-six years old. His age adds a deeper resonance to the lines he speaks at the beginning of the graveyard scene:

You know as well as I do that the dead don’t stay interested in us living people for very long. Gradually, gradually, they lose hold of the earth…and the ambitions they had…and the pleasures they had…and the things they suffered…and the people they loved.

They get weaned away from earth–that’s the way I put it,–weaned away.

As I listened to Whitmore last Wednesday night, I remembered the Old Burying Ground, and the shyly modest plaque tucked alongside the handsome gravestone inscribed with a line from a ninety-year-old novel that continues to be read. What will survive of us is love, I thought, recalling the poem by Philip Larkin that last came to my mind when, two and a half years ago, I turned on a car radio and heard by chance the recorded voice of a friend who had died a decade earlier.

The next morning Mrs. T and I paid a visit to Peterborough’s East Hill Cemetery, an out-of-the-way spot that many well-informed locals believe to be the original of the unnamed cemetery in Our Town, though Wilder himself never admitted as much. So far as I could tell, no one has been buried there since 1932, but the Petersborough Historical Society continues to maintain the grounds and looks after the increasingly fragile headstones. East Hill is steep and there’s nowhere to park, so we left our rented car by the side of the road and started climbing. Within a minute or two we felt as though we’d stepped through a curtain into a lost world, one that Wilder’s Stage Manager describes with haunting precision:

The next morning Mrs. T and I paid a visit to Peterborough’s East Hill Cemetery, an out-of-the-way spot that many well-informed locals believe to be the original of the unnamed cemetery in Our Town, though Wilder himself never admitted as much. So far as I could tell, no one has been buried there since 1932, but the Petersborough Historical Society continues to maintain the grounds and looks after the increasingly fragile headstones. East Hill is steep and there’s nowhere to park, so we left our rented car by the side of the road and started climbing. Within a minute or two we felt as though we’d stepped through a curtain into a lost world, one that Wilder’s Stage Manager describes with haunting precision:

This is certainly an important part of Grover’s Corners. It’s on a hilltop–a windy hilltop–lots of sky, lots of clouds,–often lots of sun and moon and stars….

Yes, beautiful spot up here. Mountain laurel and li-lacks. I often wonder why people like to be buried in Woodlawn and Brooklyn when they might pass the same time up here in New Hampshire.

Over there–

Pointing to stage left

are the old stones,–1670, 1680. Strong-minded people that come a long way to be independent. Summer people walk around there laughing at the funny words on the tombstones…it don’t do any harm. And genealogists come up from Boston–get paid by city people for looking up their ancestors. They want to make sure they’re Daughters of the American Revolution and of the Mayflower…Well, I guess that don’t do any harm, either. Wherever you come near the human race, there’s layers and layers of nonsense….

Yes, an awful lot of sorrow has sort of quieted down up here.

People just wild with grief have brought their relatives up to this hill. We all know how it is…and then time…and sunny days…and rainy days…’n snow…We’re all glad they’re in a beautiful place and we’re coming up here ourselves when our fit’s over.

Those words echoed in my mind’s ear as we walked around the cemetery, pausing from time to time to read the wholly unfunny words on the oddly tilted stones. Prepare for Death and follow me: that’s the last line of the half-legible quatrain carved at the base of the tombstone of Samuel Stinson, who died in 1771 and now reposes on East Hill, surrounded by his family. Might Wilder have had him in mind when he gave a name to Simon Stimson, the drunken, unhappy choirmaster of Our Town?

Mrs. T and I didn’t have much to say as we made our way back down the hill. A light summer shower was falling, just as it does in the last act of Our Town, and we were each lost in our separate thoughts. Once more I recalled the words of the Stage Manager, a role that Thornton Wilder played on several occasions, both in summer-stock productions and on Broadway for two weeks in September of 1938:

There are the stars–doing their old, old crisscross journeys in the sky. Scholars haven’t settled the matter yet, but they seem to think there are no living beings up there. Just chalk…or fire. Only this one is straining away, straining away all the time to make something of itself. The strain’s so bad that every sixteen hours everybody lies down and gets a rest.

He winds his watch.

Hm….Eleven o’clock in Grover’s Corners.–You get a good rest, too. Good night.

For those of us still on earth, straining to make something of ourselves, it seems there is no weaning away from the people we love and lose: they are always there, dissolved into the completeness of eternity, waiting patiently–and, I suspect, indifferently–for the little resurrection that is memory.