Last week I got drunk on the New Mexico landscape, at once violent and austere, colorful and stark, framed by soaring mountain ranges and a vast blue bowl of sky. It is an aesthete’s delight and an artist’s despair, for its beauty is so breathtaking as to defy the power of mere mortals to suggest, though countless artists have done what they could to convey its quality. Richard Diebenkorn did better than most when he painted a series of landscape-inspired abstract canvases in Albuquerque between 1950 and 1952, many of which are currently on view at the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. and one of which is reproduced on the cover of the Santa Fe Opera‘s 2008 souvenir program. (I saw it when the Phillips exhibition was on display in New York a few months ago.)

Last week I got drunk on the New Mexico landscape, at once violent and austere, colorful and stark, framed by soaring mountain ranges and a vast blue bowl of sky. It is an aesthete’s delight and an artist’s despair, for its beauty is so breathtaking as to defy the power of mere mortals to suggest, though countless artists have done what they could to convey its quality. Richard Diebenkorn did better than most when he painted a series of landscape-inspired abstract canvases in Albuquerque between 1950 and 1952, many of which are currently on view at the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. and one of which is reproduced on the cover of the Santa Fe Opera‘s 2008 souvenir program. (I saw it when the Phillips exhibition was on display in New York a few months ago.)

The best of these paintings do more than hint at what Willa Cather had in mind when she wrote about New Mexico in Death Comes for the Archbishop:

From the flat red sea of sand rose great rock mesas, generally Gothic in outline, resembling vast cathedrals. They were not crowded together in disorder, but placed in wide spaces, long vistas between. This plain might once have been an enormous city, all the smaller quarters destroyed by time, only the public buildings left,–piles of architecture that were like mountains. The sandy soil of the plain had a light sprinkling of junipers, and was splotched with masses of blooming rabbit brush,–that olive-coloured plant that grows in high waves like a tossing sea, at this season covered with a thatch of bloom, yellow as gorse, or orange like marigolds.

I didn’t get to see much of New Mexico when I flew out to Santa Fe two months ago to attend the press conference at which the cast and production team for the premiere of The Letter were announced. I had to race back to Manhattan the next day to cover a Broadway opening, so I ended up spending a grand total of sixteen hours in Santa Fe, more than half of them in darkness. Even then, though, I wondered whether the work that Paul Moravec and I are writing for the Santa Fe Opera would be upstaged by the countryside that surrounds the 2,128-seat outdoor theater where the company performs each summer–not to mention the theater itself, whose architectural design is a perfect complement to the 7,500-foot-high mesa atop which it sits.

I didn’t get to see much of New Mexico when I flew out to Santa Fe two months ago to attend the press conference at which the cast and production team for the premiere of The Letter were announced. I had to race back to Manhattan the next day to cover a Broadway opening, so I ended up spending a grand total of sixteen hours in Santa Fe, more than half of them in darkness. Even then, though, I wondered whether the work that Paul Moravec and I are writing for the Santa Fe Opera would be upstaged by the countryside that surrounds the 2,128-seat outdoor theater where the company performs each summer–not to mention the theater itself, whose architectural design is a perfect complement to the 7,500-foot-high mesa atop which it sits.

Paul and I have just spent four full days and nights in Santa Fe, long enough for me to look around town in between shows and get something of a feel for the place where the Santa Fe Opera makes its home. Most of our time, though, was spent at the “ranch” at the end of Opera House Drive, where we conferred with many of the people who will be helping to put The Letter on stage next July and spent our evenings watching the company at work.

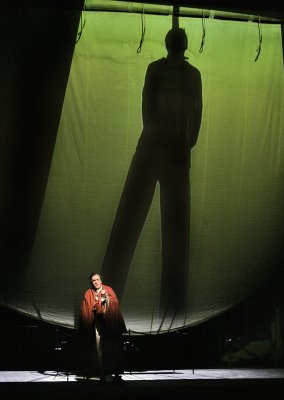

Now that I’ve finally seen the Santa Fe Opera perform, I feel reasonably confident that The Letter won’t get lost amid the surrounding scenery–in part because the man-made scenery I saw last week was so remarkable. Robert Innes Hopkins’ set for Benjamin Britten’s Billy Budd, most of which takes place on the main-deck and quarter-deck of H.M.S. Indomitable, is a spectacular piece of naturalistic design tinged with expressionism, and the sets for The Marriage of Figaro (by Paul Brown) and Falstaff (by Allen Moyer) are slightly less sensational but no less impressive or effective. I am, to be sure, a biased witness, but the productions as a whole seemed to me as good as any I’d seen anywhere, while Billy Budd, staged by Paul Curran, was the best Budd I’ve ever seen, period.

Now that I’ve finally seen the Santa Fe Opera perform, I feel reasonably confident that The Letter won’t get lost amid the surrounding scenery–in part because the man-made scenery I saw last week was so remarkable. Robert Innes Hopkins’ set for Benjamin Britten’s Billy Budd, most of which takes place on the main-deck and quarter-deck of H.M.S. Indomitable, is a spectacular piece of naturalistic design tinged with expressionism, and the sets for The Marriage of Figaro (by Paul Brown) and Falstaff (by Allen Moyer) are slightly less sensational but no less impressive or effective. I am, to be sure, a biased witness, but the productions as a whole seemed to me as good as any I’d seen anywhere, while Billy Budd, staged by Paul Curran, was the best Budd I’ve ever seen, period.

I was especially interested in Figaro because it was directed by Jonathan Kent, who will be staging The Letter, and Falstaff because the title role is currently being sung by Anthony Michaels-Moore, one of the stars of our opera. Anthony has been cast as Robert Crosbie, the cuckolded husband who was played by Herbert Marshall in William Wyler’s 1940 film version of the Somerset Maugham play on which The Letter is based.

I last saw Anthony at the Metropolitan Opera House earlier this season–he was singing Balstrode in Britten’s Peter Grimes–and I was amazed to discover on Tuesday that among his myriad gifts, he can be funny. Not that he’ll be cracking jokes in The Letter, but comedy, as everyone knows, is harder to play than tragedy, and Anthony pulled it off with awesome aplomb. “It’s the fat suit, really,” he modestly told me the day after his debut. “When you put it on, something happens.” Maybe, but there has to be something there in the first place, and that mysterious “something” is very much there in in Anthony’s case.

As for Jonathan Kent’s Figaro, it’s obviously not for me to praise the work of the man who’ll be directing The Letter. Instead I’ll quote from my Wall Street Journal review of the 2006 Broadway revival of Brian Friel’s Faith Healer, which I wrote many months before I knew that I would be working with Jonathan:

The original Broadway production of “Faith Healer,” which starred James Mason, ran for just 20 performances. I didn’t see it then and so can say nothing about its initial failure to hold the stage. Perhaps a quarter-century’s worth of one-person shows has awakened New York playgoers to the theatrical power of the extended monologue. Whatever the reason, this revival is making an overwhelmingly powerful impression on the audiences who see it, as well it should.

For my part, I came away humbled by the collective mastery of the artists who are bringing “Faith Healer” to blazing life each night. Gifted as they are, though, it is Brian Friel who deserves the highest praise of all. Once again he has proved art’s power to narrow the fearful gap that separates soul from soul. Like every great writer, he reveals us to one another–and to ourselves.

The preview of Faith Healer that I saw was one of the most unforgettable nights I’ve been privileged to spend in a theater, and when Richard Gaddes, who runs the Santa Fe Opera, asked Paul and me whether we thought Jonathan would be a suitable choice to direct The Letter, I nearly fell out of my chair.

(First of two parts)