I’m currently weaning myself off coffee so consider the post title above as suffused with longing. I’ve spent the last couple days at one cup a day (down from a steady day-long drip) and so feel a little flattened and pre-lingual and Flowers for Algernonish. Yet in the midst of the bleakness a few animating things present themselves:

• The portfolio of poems by Jack Spicer included in the July/August issue of Poetry, the contents of which the magazine has available online (scroll down). I wasn’t familiar with Spicer’s work before — Lowell was, but he knows his California poets — but I’m completely enamored. A couple to explore are “Any fool can get into an ocean…” and “Imagine Lucifer.”

The magazine notes that a volume of Spicer’s collected poetry, My Vocabulary Did This To Me (that title is taken from the poet’s reported last words), is forthcoming from Wesleyan University Press this fall. A collection of his lectures on poetry, The House That Jack Built, has already been out for some time. You can read an excerpt of one of the lectures here, although I recommend reading this introduction along with it as well as this brief bio of Spicer.

• A while back Rockslinga had a sampling of quotations from Zadie Smith’s essay on novel-writing in the June Believer. I finally picked up a copy of the magazine and I’m so glad I did. Originally given as a lecture at Columbia University, the essay’s one of the most helpful pieces I’ve read about long-haul fiction writing, a nice blend of practical advice with the abstractly inspiring. Unfortunately, it’s only partly available online, which doesn’t do you much good at your desk right now, does it? So until you can procure your own copy, you can read Smith’s very fine essay on Kafka in the current issue of New York Review of Books.

Smatterings elsewhere:

• As the future of the L.A. Times Book Review is considered, Mark “TEV” Sarvas proposes a possible new incarnation for the review as an online powerhouse a la The Guardian. Discussion is invited in the comments, and I point it out as it’s interesting to consider how papers will/ should adapt their book coverage in the future. (Aside: If you’re not reading it already, the L.A. Times book blog, Jacket Copy, is excellent.)

• Fernham provides a report on a lecture she attended on the Borges translation of Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own (short version: liberties were taken).

Archives for July 2008

TT: Snapshot

Nat “King” Cole sings “Sweet Lorraine,” accompanied by Coleman Hawkins and the Oscar Peterson Trio, with Herb Ellis on guitar and Ray Brown on bass:

(This is the latest in a weekly series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Wednesday.)

TT: Almanac

“Pity the selfishness of lovers: it is brief, a forlorn hope; it is impossible.”

Elizabeth Bowen, The Death of the Heart

TT: Due to circumstances…

I just found out that the alternate URL for this site, www.terryteachout.com, has been out of order for the past few days. Don’t know why, and it’s hard to get anything fixed in July, but rest assured that we’re working on it.

In the meantime, you can always view About Last night by going to www.artsjournal.com/aboutlastnight, so please spread the word.

BOOK

Sybille Bedford, A Legacy (Counterpoint, $16). All of the adjectives Sybille Bedford’s writing brings to mind belong to the same family: sharp, acute, penetrating, piercing, and so on. In her most famous novel, two marriages, inauspicious in different ways, bind together the fates of three families in late 18th- and early 19th-century Germany. How could it have taken me this long to discover Bedford? Why isn’t a writer with her observational powers, slicing wit, and historical grasp–a woman whose work no less a cutting edge than Dorothy Parker found “almost terrifyingly brilliant”–better known? The curious can start with A Legacy, whose certainties and mysteries stand in perfect balance (OGIC).

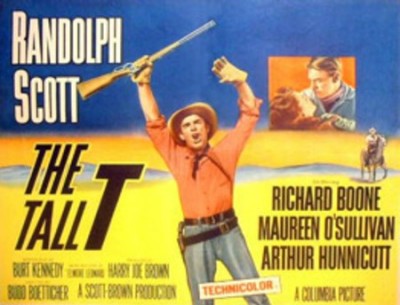

TT: Doing it for Randolph Scott

Attention, film buffs! For those of you who, like me, treasure the Hollywood western at its smartest and most aesthetically compelling, a piece of stop-press news has been eddying through the Internet for the past month or so, courtesy of the in-house blog of Tapeworks Recording Studios in Hartford, Connecticut. It finally caught up with me yesterday:

Attention, film buffs! For those of you who, like me, treasure the Hollywood western at its smartest and most aesthetically compelling, a piece of stop-press news has been eddying through the Internet for the past month or so, courtesy of the in-house blog of Tapeworks Recording Studios in Hartford, Connecticut. It finally caught up with me yesterday:

It was a B Movie bonanza in Tapeworks today as noted film authority Jeanine Basinger narrated a companion DVD track to the Budd Boetticher Western, The Tall T, starring Randolph Scott and Maureen O’Sullivan.

This is the first in a series of Boetticher releases that will comprise a box set of the directors distinctive works.

A regular presence in the Hartford recording studio, Prof. Basinger has provided commentary on numerous titles while viewing the films with Chief Engineer Bill Ahearn at Tapeworks and simultaneously with a Hollywood production company on the digital patch.

Jeanine Basinger is Corwin-Fuller Professor of Film Studies and Founder and Curator of the Cinema Archives at Wesleyan University, Middletown, Connecticut.

For those of you just joining us, I’ve been fulminating for years about the fact that only one of the six classic films starring Randolph Scott and directed by Budd Boetticher, Seven Men from Now, has been transferred to DVD. The Teachout Reader contains an essay about the Boetticher-Scott westerns (you can read it here) in which I praise them at length and in the strongest possible terms:

For those of you just joining us, I’ve been fulminating for years about the fact that only one of the six classic films starring Randolph Scott and directed by Budd Boetticher, Seven Men from Now, has been transferred to DVD. The Teachout Reader contains an essay about the Boetticher-Scott westerns (you can read it here) in which I praise them at length and in the strongest possible terms:

The clean, spare look of the Boetticher-Scott films is mirrored in their no-nonsense scripts. Ride Lonesome and Comanche Station, both written by Burt Kennedy, are for all intents and purposes the same movie as Seven Men from Now–the basic plot mechanism is recycled from film to film, along with a few choice snippets of dialogue–while Decision at Sundown and The Tall T, the former doctored by Kennedy and the latter adapted by him from a novel by Elmore Leonard, arise from different situations but develop in similar ways. More often than not, Scott plays the part of a solitary, vengeful drifter who is searching for a man has wronged him, usually by murdering his wife. In the course of his travels, he meets an unhappily married woman, to whom he is powerfully and illicitly attracted, and a villain who is charming and courageous–a hero gone bad, in other words. The villain proves to be looking for the same man as Scott, but their interests are in conflict, forcing them into a climactic showdown.

What sounds repetitive on paper proves miraculously varied in practice. Just as Degas never tired of the ballet dancers he painted time and again, so does Boetticher come up with ever-fresh ways to frame his players among the sun-scorched rocks of Lone Pine, finding painfully austere beauty in that least seductive of landscapes….

Now coming to a DVD player near you? It sure looks like it–and about damn time, too.

I’ll keep you posted.

TT: Almanac

“Those who claim to enjoy music fully only if their eyes are closed do not hear it better than if their eyes were open, but the absence of visual distractions allows them to abandon themselves, under the lulling influence of sounds, to vague reveries–and it is these which they love, far more than music itself.”

Igor Stravinsky, Autobiography

TT: Men at work (VII)

I came back to New York from my last reviewing trip and found on my kitchen table a package from Subito Music, Paul Moravec‘s publisher. It contained a printed copy of the complete working draft of the piano-vocal score of The Letter, the opera that Paul and I are writing together. I’d already gone over every measure of The Letter time and again, but it’s one thing to read a score on a computer screen and another to hold in your hands a bound volume whose cover reads as follows:

Paul Moravec

THE LETTER

An Opera in Eight Scenes

Libretto by Terry Teachout

After the play by W. Somerset Maugham

What once was not quite real has become solid and touchable, and the fact that the Santa Fe Opera will be premiering The Letter a year from now seems less fantastic and more believable.

Later this month Paul and I will fly out to Santa Fe to see four of the five productions that the company is mounting this season. One of them, The Marriage of Figaro, was staged by Jonathan Kent, the man who will be directing The Letter next summer. I stood on the stage of the Crosby Theater two months ago, but I’ve never seen an opera performed there, and Paul and I expect to make some changes in The Letter after immersing ourselves in Figaro, Falstaff, Billy Budd and Kaija Saariaho’s Adriana Mater. Once we’re finished, Subito will print a revised edition of the piano-vocal score that will be sent out to the cast and production team, and Paul will start orchestrating The Letter, a back-breaking job that will take him several months to finish.

Later this month Paul and I will fly out to Santa Fe to see four of the five productions that the company is mounting this season. One of them, The Marriage of Figaro, was staged by Jonathan Kent, the man who will be directing The Letter next summer. I stood on the stage of the Crosby Theater two months ago, but I’ve never seen an opera performed there, and Paul and I expect to make some changes in The Letter after immersing ourselves in Figaro, Falstaff, Billy Budd and Kaija Saariaho’s Adriana Mater. Once we’re finished, Subito will print a revised edition of the piano-vocal score that will be sent out to the cast and production team, and Paul will start orchestrating The Letter, a back-breaking job that will take him several months to finish.

At that point the main part of my work will be done, and I’ll turn my energies to seeing Rhythm Man: A Life of Louis Armstrong into print. Harcourt plans to publish Rhythm Man next spring, and after the hoopla, such as it is, has died down, I’ll go back to Santa Fe to help prepare for the premiere of The Letter. Operas, like plays, tend to get revised at the last minute, and even though this one is far ahead of schedule, I have little doubt that my services will be required when The Letter goes into rehearsal.

I wonder what Somerset Maugham would have thought of my libretto for The Letter, which follows the structural outline of his 1927 play with reasonable faithfulness but is otherwise radically different in tone, text, and detail from what he wrote. The impetus for these changes came from Paul, who was concerned from the start about the coldness with which Maugham portrayed his characters, especially Leslie Crosbie, the play’s murderous anti-heroine. Maugham, of course, was a notorious cynic, though he affected to pretend otherwise. “If it’s cynical to look truth in the face and exercise common sense in the affairs of life, then certainly I’m a cynic and odious if you like,” says the narrator of one of his short stories. The problem is that opera isn’t about common sense. “Opera isn’t a cynical medium,” Paul told me early on. “It’s a lyrical medium. These people have to have a reason to be singing. If they don’t, they’ll look silly up there.”

I wonder what Somerset Maugham would have thought of my libretto for The Letter, which follows the structural outline of his 1927 play with reasonable faithfulness but is otherwise radically different in tone, text, and detail from what he wrote. The impetus for these changes came from Paul, who was concerned from the start about the coldness with which Maugham portrayed his characters, especially Leslie Crosbie, the play’s murderous anti-heroine. Maugham, of course, was a notorious cynic, though he affected to pretend otherwise. “If it’s cynical to look truth in the face and exercise common sense in the affairs of life, then certainly I’m a cynic and odious if you like,” says the narrator of one of his short stories. The problem is that opera isn’t about common sense. “Opera isn’t a cynical medium,” Paul told me early on. “It’s a lyrical medium. These people have to have a reason to be singing. If they don’t, they’ll look silly up there.”

Somewhere along the way Paul sent me a quotation from Gary Schmidgall’s Literature as Opera in which Schmidgall talks about Tchaikovsky’s operatic version of Yevgeny Onegin: “The need to deflate, ridicule, and debunk that is present in Pushkin’s verse is replaced by Tchaikovsky’s need to sympathize with, draw near to, and grasp the innermost passions he is setting to music.” I saw at once what Paul was getting at, and thereafter I did everything I could to open up the constricted emotional world of The Letter, whose limitations remind me of something that Maugham wrote about himself in The Summing Up, his 1938 memoir: “I have most loved people who cared little or nothing for me and when people have loved me I have been embarrassed.”

By the time we were done, Paul and I had created a free-standing, fully independent work of art whose emotional climate is far removed from that of Maugham’s play, and even more so from the hard-nosed short story on which it is based. In “The Letter,” which predates the stage version by three years, Leslie Crosbie comes off as–to put it mildly–a real piece of work:

By the time we were done, Paul and I had created a free-standing, fully independent work of art whose emotional climate is far removed from that of Maugham’s play, and even more so from the hard-nosed short story on which it is based. In “The Letter,” which predates the stage version by three years, Leslie Crosbie comes off as–to put it mildly–a real piece of work:

Her face was no longer human. It was distorted with cruelty, and rage and pain. You would never have thought that this quiet, refined woman was capable of such a fiendish passion. Mr. Joyce took a step backwards. He was absolutely aghast at the sight of her. It was not a face, it was a gibbering, hideous mask.

Maugham’s Leslie would never have sought to explain her unfaithfulness to her husband in the way that ours does:

Imagine a woman

Alone in the jungle,

Alone with the servants,

Nowhere to go, nothing to do

But watch the clock and knit.

Sick of the heat,

Sick of the smell,

Sick of being a planter’s wife,

I was sick with loneliness.

You had your work,

You had your friends–

And I had Geoff!

He was my life,

My love,

And then…

I shot him.

Maugham was a man of the theater, that most empirical of art forms, and he also liked opera and knew a fair amount about it, so I assume–perhaps wrongly–that he would have understood why Paul and I felt the need to change his play in the ways that we did. Nor was I surprised by the distance that we traveled in writing The Letter. I’ve written quite a lot about opera over the years, and in “Brand-Name Opera,” a 1998 essay collected in A Terry Teachout Reader, I analyzed the weaknesses of André Previn’s operatic version of A Streetcar Named Desire, one of which is that the libretto fails to add anything to Tennessee Williams’ play:

Because the play is so famous–and because the Williams estate required him to do so–Philip Littell, the librettist, stuck closely both to its broad structural outlines and to its verbal essence. “The trick,” Littell has said, “is to make [the audience] think, ‘Why’d they hire a librettist?'” In this he has succeeded; despite extensive cuts and countless small textual changes, anyone who has seen the play will find Littell’s libretto to be impressively true to its spirit.

But to turn a famous piece of literature into an effective opera libretto entails far more than merely compressing the original text. Every great opera based on a familiar literary source involves an imaginative transformation of the original, one that typically goes far beyond the setting of old words to new music. In Verdi’s Otello and Falstaff, Shakespeare’s English words are freely translated into the Italian of Arrigo Boito; in Tchaikovsky’s Yevgeny Onegin, Alexander Pushkin’s verse novel is opened up into a series of “lyrical scenes”; in Benjamin Britten’s The Turn of the Screw, Henry James’s narrative voice is jettisoned in favor of dialogue, almost none of which appears in the original novella.

In the absence of such a transformation, one is almost inevitably left with an impression of mere tautology; and that is the case with Streetcar. Lotfi Mansouri, the general director of the San Francisco Opera, had long wanted to turn Williams’s play into an opera, and approached several composers before settling on Previn. “I cornered Stephen Sondheim,” he has recalled, “and he said, ‘Oh, it’s such a good play–it doesn’t need music.’ Well, you can say that about Shakespeare’s Othello too.” But Boito’s Otello is a good libretto precisely because it is so different from Shakespeare’s Othello. By contrast, Littell’s Streetcar is so much like the original play that it is difficult at first glance to see why André Previn felt the need to set it to music.

I had no idea ten years ago that I would someday be putting those words into practice.

Needless to say, I’m no Boito–I think that Otello and Falstaff are the greatest opera libretti ever written–but I also think that he would have understood what I was trying to do in writing The Letter. While it’s not for me to say whether I succeeded, I feel safe in saying that Paul has set my words with the utmost effectiveness, and I hope that when the time comes, our audiences will find them worthy of his music.