I spend a fair amount of each summer watching outdoor shows. The weather being what it is, you’d think I’d have gotten rained out at least a half-dozen times by now, but until this past weekend it had only happened once, in New York last year, and since I live a block away from Central Park, where the Public Theater gives its Shakespeare in the Park performances, I was able to catch the same show the next night.

My luck finally ran out on Saturday. I picked up a Zipcar at noon and drove to the suburbs of Baltimore to see Chesapeake Shakespeare Company perform The Tempest. The weather was beautiful when I hit the road, but no sooner did I reach the Ellicott City exit than a real-life tempest, complete with lightning, rolled over the horizon. I checked into my hotel and called the company publicist, who confirmed what I already knew: no show tonight. Alas, I had to leave for to New York at six-thirty the following morning in order to catch a midday train, so Chesapeake Shakespeare will have to wait until next year.

So what do you do in the suburbs of Baltimore on a rainy Saturday night? Not a hell of a lot, as far as I can tell. I spent an hour looking for a decent restaurant, but every place that looked promising was booked solid. Instead I ended up downing a nondescript sandwich and returning to my equally nondescript hotel room, where I surfed the Web, caught up on my e-mail, and passed a couple of pleasant hours polishing Rhythm Man: A Life of Louis Armstrong. George Avakian, who knew Armstrong and produced several of his best-known recordings, has been kind enough to spend the past couple of weeks reading the manuscript and sending me his comments, so I devoted part of my unplanned night off to making various changes based on his astute suggestions.

So what do you do in the suburbs of Baltimore on a rainy Saturday night? Not a hell of a lot, as far as I can tell. I spent an hour looking for a decent restaurant, but every place that looked promising was booked solid. Instead I ended up downing a nondescript sandwich and returning to my equally nondescript hotel room, where I surfed the Web, caught up on my e-mail, and passed a couple of pleasant hours polishing Rhythm Man: A Life of Louis Armstrong. George Avakian, who knew Armstrong and produced several of his best-known recordings, has been kind enough to spend the past couple of weeks reading the manuscript and sending me his comments, so I devoted part of my unplanned night off to making various changes based on his astute suggestions.

I’m pleased to say that George didn’t have any suggestions to make about the following passage:

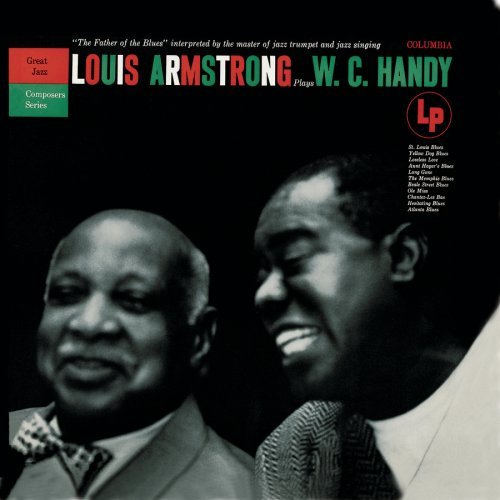

Avakian was eager to record Armstrong for Columbia. The only stumbling block was that Joe Glaser, the trumpeter’s manager, who had no interest in presenting him as anything other than a popular entertainer, was content to stick with Decca, his old label. How to change Glaser’s mind? It was Jim Conkling, the president of Columbia, who came up with the solution: Avakian’s Louis Armstrong Story reissues had been selling well, but the trumpeter, who had recorded all of the original OKeh 78 sides on which they were based for flat one-time cash payments, wasn’t making a dime off them. Why not offer him a one-percent royalty on Columbia’s OKeh reissues in return for signing an exclusive contract? That was the kind of talk the money-conscious Glaser understood. In short order the deal was done, and on July 12, 1954, Armstrong and the All Stars began taping Louis Armstrong Plays W.C. Handy, the best album they ever made.

The project was Avakian’s idea. “For years I had planned that one day, when possible, I would make a series of albums with Pops,” he said later. “He was an artist who should have been represented in unified packages, complete with explanatory notes.” The music of the “Father of the Blues” (as Handy had long billed himself) was a logical starting point for the series, and Armstrong, who had been identified with Handy’s “St. Louis Blues” ever since he recorded it with Bessie Smith in 1925, was more than agreeable. “You choose the tunes,” he said. “You know me, you know what I like.” Avakian picked eleven of Handy’s best-known songs and sent the music to Armstrong, who worked the tunes up on the road. A few weeks later he called the producer at home. “I’m laying over in Chicago next month for a few days,” he said. “Line up the studio and I’ll be ready.” Avakian immediately booked three afternoon sessions in a Chicago studio. “Louie came in with no music beyond the sheet music I’d given him and a few sketches that Billy Kyle had made,” he recalled. “‘We can work out these longer performances any way you want,’ he said, ‘but why don’t you choose the order of the solos? I don’t want to do these things the way we’d do them in a club. It’ll be fresh for us that way.'”

That was what Avakian wanted to hear. Except for the “New Orleans Function” session, at which Milt Gabler had allowed the All Stars to play more or less the way they did on stage, virtually all of Armstrong’s studio recordings for Decca had conformed rigidly to the three-minute, three-chorus mold of his old 78s. Avakian, by contrast, proposed to bring him into the age of the long-playing record. Not only was Louis Armstrong Plays W.C. Handy to be a thematically unified, meticulously sequenced single-composer album, but most of the songs on it ran well past the three-minute mark, including an album-opening version of “St. Louis Blues” that played for nearly nine minutes. It was, in short, a concept album avant la lettre, recorded seven months before Frank Sinatra and Nelson Riddle “invented” the genre with In the Wee Small Hours.

Armstrong responded enthusiastically but not passively to his producer’s musical suggestions. Rehearsal tapes made at the sessions and released in 1996 show that he played a dominant role in structuring and polishing the arrangements heard on the album. But it was Avakian who gave to Louis Armstrong Plays W.C. Handy its shape and conceptual unity, and it says much about Armstrong’s receptivity that he was not merely willing to accept the younger man’s tactful guidance, but capable of acknowledging the quality of the results. “I can’t remember when I felt this good about making a record,” he told Avakian after the album was edited and ready for release. He was right to feel that way. From the first bar of “St. Louis Blues” onward, it is evident that Louis Armstrong Plays W.C. Handy represents something new in Armstrong’s recorded oeuvre. Not since the studio-only Hot Fives and Sevens had he made a record that did more than merely document the way he played in public–that was, instead, an art object in its own right….

I also caught up with Ricky Riccardi’s The Wonderful World of Louis Armstrong, one of the most original and significant jazz blogs to come along since I first started keeping up with the blogosphere seven years ago. Riccardi is a musician, scholar, and Armstrong enthusiast who is writing a book about the All Stars, the six-piece combo that Armstrong led from 1947 until his death in 1971. He knows as much about Armstrong as anyone in the world, myself included, and in 2007 he generously decided to share the fruits of his labors by starting a blog on which he posts at irregular but fairly frequent intervals about his hero’s records.

Judging by what he’s written to date, Ricky’s book will be a major contribution to the Armstrong literature, and I’ve made extensive use of his postings in writing Rhythm Man. Among countless other things, it was The Wonderful World of Louis Armstrong that first drew my attention to this kinescope of the All Stars performing “On the Sunny Side of the Street” on CBS in 1958. It’s my favorite film of Armstrong in performance:

Here’s a typical example of Ricky at work, an excerpt from his posting about the 1933 big-band recording of Harold Arlen’s “I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues,” to my mind one of Armstrong’s half-dozen finest recordings:

After the vocal, the band swings out for awhile, Armstrong clearly enjoying their playing, growling out a “Yeah” when they begin. Teddy Wilson sounds especially good here, as does the entire band, propelled by Bill Oldham’s big-toned bass (when he switched to tuba for the April 1933 sessions, it was a step backward). It’s a long showcase for the band but fortunately, there’s 90 seconds of record left and Pops makes the most of it, opening with one of his all-time greatest entrances: a single held D (listen for one of the saxes goof up and hit a quick note under it). Perhaps the Armstrong of 1928 would have played something flashy and jaw-dropping in this two-bar break, but the Armstrong of 1933 had already matured greatly and he knew he could convey just as much drama and feeling with a perfectly placed held note. I mean, really, how do you make one held note swing? It’s all in the placement, my friends. Armstrong hits it a shade after the beat and the whole thing swings.

This is what I wrote in Rhythm Man about the same recording:

“I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues,” one of Armstrong’s immortal masterpieces, is as worthy of comparison with “West End Blues” as it is different from that riot of virtuosity. Here it is the trumpet solo that seizes our attention, for Armstrong, in a departure from his customary practice on ballads, dispenses almost completely with Arlen’s melody, substituting instead a series of rhythmically free phrases that lead upward to a high B flat. Four times he falls off from that shining note–and then comes the fifth fall, at the bottom of which he changes course and swoops gracefully upward to a full-throated high D whose vibrance was perfectly caught by Victor’s recording engineer. It is a show-stopping stroke, yet there is no trace of overstatement about it: if anything Armstrong seems to have broken through to a realm of abstract lyricism that transcends ordinary human emotion. Only then does he condescend to ease back into the vicinity of the tune, returning the bedazzled listener to the everyday world.

And that’s what I did on a rainy Saturday night in suburban Baltimore.

What about you, OGIC and CAAF? Have you anything to declare?