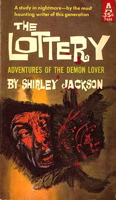

As Lauren notes (see the July 23rd event), this summer marks the 60th anniversary of the publication of Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery.” Through sheer coincidence, I recently re-read the story for my book club, along with Jackson’s masterful last novel, We Have Always Lived in the Castle.* If you can, it’s worth it to check out the Penguin edition of We Have Always Lived in the Castle, which features a great, perceptive introduction by Jonathan Lethem (sadly not available online).

As Lauren notes (see the July 23rd event), this summer marks the 60th anniversary of the publication of Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery.” Through sheer coincidence, I recently re-read the story for my book club, along with Jackson’s masterful last novel, We Have Always Lived in the Castle.* If you can, it’s worth it to check out the Penguin edition of We Have Always Lived in the Castle, which features a great, perceptive introduction by Jonathan Lethem (sadly not available online).

The precise anniversary of “The Lottery” is tomorrow, in fact. The story was originally published in the June 26th, 1948 issue of The New Yorker — a date that neatly coincides with the story’s first line — and, as Lethem notes in the introduction of We Have Always Lived in the Castle, its appearance caused a storm of controversy. Subscriptions were cancelled, and Jackson received bags of hate mail “denouncing the story as ‘nauseating,’ ‘perverted,’ and ‘vicious.'” (According to its Wikipedia page, the story was even banned in South Africa.)

1948 is also the same year The New Yorker published J.D. Salinger’s “A Perfect Day For Bananafish,” another story that ends with a rather shocking, unexpected death. I’m sure some enterprising PhD thesis has already been done on the topic, but I’m curious about how both stories relate to the field of psychology as it stood in the late ’40s: Behaviorism ascendant, Freud and Jung still in the air and about to rise again. Like most of Salinger, “Bananafish” can be read as a flat rejection of psychology’s ability to ever explain the mysterious self, whereas Jackson seems to have embraced the field, as if she used its concepts and terminology as a jumping-off point for her art. Haunting Of Hill House, for example, reads like a hothouse catalog of Freudian concepts. (Interesting to note, though, that “The Lottery,” which could serve as a case study in the brutal pathology of group think, anticipated the Milgram experiment by about 13 years.)

As Lethem writes about Jackson’s work:

Though she teased at explanations of sorcery in both her life and her art (an early dust-flap biography called her “a practicing amateur witch,”** and she seems never to have shaken the effects of this debatable publicity strategy) Jackson’s great subject was precisely the opposite of paranormality. The relentless, undeniable core of her writing–her six complete novels and the twenty-odd fiercest of her stories–conveys a vast intimacy with everyday evil, with the pathological undertones of prosaic human configurations: a village, a family, a self. She disinterred the wickedness in normality, cataloguing the ways conformity and repression tip into pyscyhosis, persecution, and paranoia, into cruelty and its masochistic, injury-cherishing twin. Like Alfred Hitchock and Patricia Highsmith, Jackson’s keynotes were complicity and denial, and the strange fluidity of guilt as it passes from one person to another.

RELATED LINK: In “Monstrous Acts and Little Murders,” another, earlier piece by Lethem about Shirley Jackson, he talks about living in North Bennington, Vermont, which provided the setting for “The Lottery.” While the town held a grudge for a while, it seems to have forgiven Jackson her trespasses.

* About half our club had never read the story before, which surprised me. I thought no one escaped junior high without writing at least one five-paragraph essay on “The Lottery.”

** Speaking of witches and Shirley Jackson: My reading of We Have Always Lived in the Castle has set me off on a Jackson kick. In my library’s holdings I was surprised to come across a book written for children called The Witchcraft of Salem Village. I’m sure I must have read it as a kid — I was ghoulish and read everything I could about Salem, desperately hoping for illustrations of the hangings, pressings by stone, etc. — but I hadn’t connected its author as being that Shirley Jackson.