The Art of Segovia (DGG, two CDs). For much of the twentieth century, Andrés Segovia was the world’s best-known guitarist, and his concerts and recordings played a key role in re-establishing the guitar as a classical instrument. Alas, he kept on playing far too long for his own good, and by the time of his death in 1987 at the age of ninety-four, his reputation was in eclipse. This two-disc set, a fabulously well-chosen anthology of Segovia’s greatest hits drawn mainly from the recital albums that he recorded for Decca in the Fifties, provides ample proof that he was every bit as good as his reputation. It contains guitar solos and transcriptions by (among others) Albéniz, Bach, Falla, Rodrigo, Roussel, Scarlatti, Tárrega, Torroba, and Villa-Lobos, all played with the grandly romantic sweep and impeccable technique that he commanded in his prime (TT).

Archives for May 2008

CD

TT: After the good die young

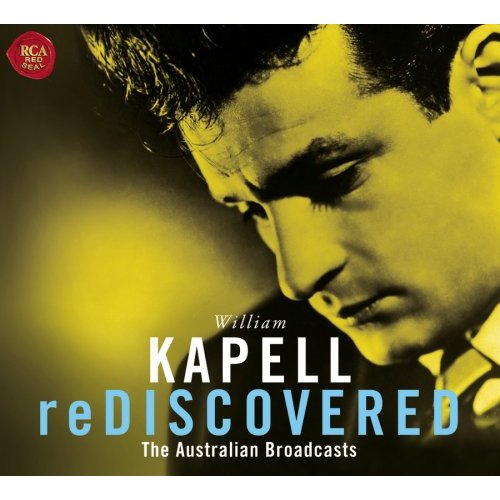

When William Kapell died in a plane crash in 1953 at the age of 31, he was well on the way to becoming an international classical-music celebrity. Instead he was forgotten. It wasn’t until his complete commercial recordings were reissued in a nine-CD box set in 1998 that a new generation of listeners discovered Kapell, and even now the fact that he was America’s greatest native-born pianist is not yet widely recognized.

When William Kapell died in a plane crash in 1953 at the age of 31, he was well on the way to becoming an international classical-music celebrity. Instead he was forgotten. It wasn’t until his complete commercial recordings were reissued in a nine-CD box set in 1998 that a new generation of listeners discovered Kapell, and even now the fact that he was America’s greatest native-born pianist is not yet widely recognized.

Earlier this month RCA released a two-CD set of live recordings made by Kapell in Australia a few weeks before he died. The release of Kapell Rediscovered is the occasion for my “Sightings” column in today’s Wall Street Journal, in which I reflect on Kapell’s brief but extraordinary career–and on the reasons why he is so poorly remembered now.

To find out why William Kapell vanished into the cultural memory hole, pick up a copy of Saturday’s Journal, turn to the “Weekend Journal” section, and see what I have to say in “Sightings.” Or read the whole thing here.

* * *

The only known video footage of Kapell’s playing is a kinescope of a TV appearance he made on Omnibus in 1953. Here it is:

CAAF: The woods are shrieking

For the past week or so, our neighborhood’s been in the throes of a full-scale cicada invasion. They emerge every 17 years in Asheville — red-eyed beasties that flutter around with metallic iridescent wings. (They look like elaborate golden clockworks when the sun hits right.) They’re everywhere, and they’re loud. As I type this, it sounds like a siren or a car alarm is going off somewhere close by. The sound starts at dawn and then dies down at dusk, hitting full volume around mid afternoon. That’s also the hardest time of day to go out for a walk; the cicadas seem to be at their most active then and can plonk you in the head as they fly by.

I asked Lowell to snap these pics. I wish he had a panoramic lens to catch the sheer plenitude. The street outside our house is littered with the various life stages of a cicada: plain brown molted exoskeletons, mating cicadas (two conjoined tail to tail), dying cicadas with quivering legs as well as dead ones, and there are grease spots running up and down the road where cars have run over them. The rest, like the ones below, are in the trees — eating and laying eggs in the branches and singing, singing.

CAAF: Minor key versus major

If Terry and OGIC are playing with Jane chords, I thought I might play too. As my first little foray into the Jane game, I decided to look up the Jane chord of the original edition of Sylvia Plath’s Ariel, which has the poems in the order Ted Hughes put them after Plath’s death, and compare it to the Jane chord of the restored edition of Ariel, which came out in 2004 and “reinstates” the order Plath had planned for the book.

In Her Husband, her excellent, balanced biography focusing on the Plath-Hughes marriage and creative partnership, Diane Middlebrook writes:

The Ariel Hughes published was not identical with the manuscript titled Ariel that Plath had organized in the black spring binder he found on her desk after her death. As editor, Hughes reshuffled the poems, destroying the narrative arc that Plath had described in her notes on the manuscript. He omitted some of the poems Plath had intended to include–he cut “The Rabbit Catcher,” for example. And he added poems that Plath had not included, poems written after she finished the Ariel manuscript, poems that Plath intended for another book. His most significant intervention was to replace the hopeful poem “Wintering”–the ending Plath had designed for Ariel–with “Edge”:

The woman is perfected.

Her dead

Body wears the smile of accomplishment.

Ariel original edition (with “The Edge” as the final poem): “Love drag.”

Ariel: The Restored Edition (with “Wintering” as the final poem): “Love spring.”*

It’s an illuminating difference, isn’t it?

But, as Meghan O’Rourke argued in Slate in 2004, while Hughes’s editing of the original Ariel manuscript is regarded with suspicion by many of Plath’s adherents (“he stole her hope!”), it may have been beneficial:

The real problem with Hughes’ interference is that we can’t separate the emotional relationship from the intellectual, artistic relationship–and we don’t trust Hughes to, either. But from this distance Plath seems fortunate to have had his input. It’s easy to forget now how radical Plath’s poetry–with its elemental female anger, its sexual voracity, its self-loathing knowingness–was in 1963. A number of the poems Plath wrote in 1961 and 1962 had been turned down by editors who didn’t understand them. Plath’s publishers in the U.K. didn’t want to publish Ariel, nor could Hughes convince Knopf, in the United States, to publish the new poems. “People didn’t understand what they were getting at, or didn’t like what they saw,” the critic A. Alvarez later told Janet Malcolm. Hughes did get Plath’s poems. And in a strange way, there is something moving about what he did. It is surely an emotionally complicated task to spend two years carefully reorganizing the work of your dead wife so as to persuade someone to publish a book that will implicate you in her tragic fate. And the irony is that, in reorganizing Ariel to emphasize the ultimate price of Plath’s emotional injuries, Hughes, like Samson, brought down the walls of the temple around him, even as he helped his wife take flight.

* To compare more fully, here are the last lines of each poem that turn the Jane chord around:

“The Edge”

The moon has nothing to be sad about,

Staring from her hood of bone.

She is used to this sort of thing.

Her blacks crackle and drag.

“Wintering”

Will the hive survive, will the gladiolas

Succeed in banking their fires

To enter another year?

What will they taste of the Christmas roses?

The bees are flying. They taste the spring.

TT: Putting a new spin on Carousel

In this week’s Wall Street Journal drama column, written from the road, I report on a New Haven show, Long Wharf Theatre’s revival of Carousel, plus an important off-Broadway event, the American premiere of Conor McPherson’s Port Authority. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

From the Broadway run of “August: Osage County” and the Off Broadway transfer of “Adding Machine” to the regional-theater Tony awarded to Chicago Shakespeare Theater, this was the season when East Coast playgoers found out for themselves that theater in Chicago is as good as it gets. Now comes yet another Windy City stunner to hammer home the point. The Court Theatre’s small-scale production of “Carousel,” co-produced with New Haven’s Long Wharf Theatre, has moved from Chicago to its second home in Connecticut. If you were impressed by Lincoln Center Theater’s handsome hit version of “South Pacific,” prepare to be floored: This “Carousel,” staged by Charles Newell, the Court’s artistic director, is the best Rodgers and Hammerstein revival I’ve ever seen.

Unlike Bartlett Sher’s freshened-up but fundamentally conventional “South Pacific,” Mr. Newell’s “Carousel” is a wholly original, deeply creative transformation of a musical that has always struck me as an uncomfortable blend of realism and sentimentality. Not since John Doyle’s similarly scaled staging of “Company” have I seen a musical revival that completely changed the way I felt about a show I thought I knew by heart….

Mr. Newell’s “Carousel” is played out on a near-bare thrust stage by a skeleton crew of 15 actors and accompanied not by a luscious-sounding pit band but a frugal 10-piece orchestra. No drummer, no synthesizer, no fancy sets, no wireless mikes, nothing but the show itself, unadorned and true. The result is a startlingly intimate “Carousel” that is all the more affecting for being so simple. Even the sentimentality becomes believable once it’s pared down to life size…

Conor McPherson, who knocked me flat in December with “The Seafarer,” is back in town with the American premiere of “Port Authority.” Written in 2002, it’s a series of interwoven monologues by three unhappy Irishmen waiting for a bus, and if that sounds like the start of an ethnic joke, don’t be thrown off the scent: The 37-year-old Mr. McPherson is already a class-A playwright, and “Port Authority,” like “The Seafarer,” comes from out of his top drawer….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Almanac

“Only two classes of books are of universal appeal: the very best and the very worst.”

Ford Madox Ford, Joseph Conrad

OGIC: Janes from James and others

My question about the Jane Chord is whether one is permitted, in the many cases in which a book begins with an article, to append the word that follows. I bet Terry’s answer is a gentle no, dear. But how much more fertile the ground of my personal library if this small cheat is granted. To wit:

The Turn of the Screw: “The story stopped.”

If you’re familiar with the particular way Henry James frames his ambiguous tale, or even just with the tale’s central ambiguity, that should give you all the frisson of a coded message arrived from beyond the grave.

What about other James? Doesn’t he just strike you as the kind of writer who would have planted such bonus meaning, in full consciousness of what he was doing? Indeed, a stroll through the corpus turns up a few beauties.

The Awkward Age: “Save tomorrow.”

The Bostonians: “Olive shed.” (!)

The Ambassadors: “Strether’s Strether.” (!!)

James’s memoir of his childhood, A Small Boy and Others: “In gap.”

Somewhere he’s chuckling, I tell you.

E. M. Forster’s epigraph to Howards End famously tells us to “Only connect”; his Jane Chord underlines the sentiment with “One never.” George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda yields the uplifting “Men noble,” while the constitutionally beclouded Thomas Hardy, in Tess of the D’Urbervilles, gives us an “On” to begin and an “on” to end; they beg for an “and” to connect them, or at least a suggestive comma.

I wish I could find my latest copy of Transit of Venus–a book that metes out its secrets as artfully as any, and that I’m certain holds some I haven’t discovered yet. But I’m forever giving that book away. Anyone?

TT: So you want to see a show?

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

Warning: Broadway shows marked with an asterisk were sold out, or nearly so, last week.

BROADWAY:

• Alfred Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps (comedy, G, suitable for bright children, reviewed here)

• August: Osage County (drama, R, adult subject matter, reviewed here)

• Avenue Q (musical, R, adult subject matter and one show-stopping scene of puppet-on-puppet sex, reviewed here)

• Boeing-Boeing (comedy, PG-13, cartoonishly sexy, reviewed here)

• Boeing-Boeing (comedy, PG-13, cartoonishly sexy, reviewed here)

• A Chorus Line (musical, PG-13/R, adult subject matter, reviewed here)

• Cry-Baby (musical, PG-13, mildly naughty and very cynical, reviewed here)

• Grease * (musical, PG-13, some sexual content, reviewed here)

• Gypsy (musical, PG-13, adult subject matter, reviewed here)

• In the Heights (musical, PG-13, some sexual content, reviewed here)

• The Little Mermaid * (musical, G, entirely suitable for children, reviewed here)

• Macbeth * (drama, PG-13, unsuitable for children, closes May 24, reviewed here)

• November (comedy, PG-13, profusely spattered with obscene language, reviewed here)

• Passing Strange (musical, PG-13, adult subject matter, reviewed here)

• South Pacific * (musical, G/PG-13, some sexual content, brilliantly staged but unsuitable for viewers acutely allergic to preachiness, reviewed here)

• Sunday in the Park with George (musical, PG-13, too complicated for children, closes June 29, reviewed here)

OFF BROADWAY:

• Adding Machine (musical, PG-13, adult subject matter, too musically demanding for youngsters, closes Aug. 31, reviewed here)

IN WASHINGTON, D.C.:

• Julius Caesar/Antony and Cleopatra (drama, PG-13, adult subject matter, too musically demanding for youngsters, performed in alternating repertory through July 6, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON OFF BROADWAY:

• From Up Here (drama, PG-13, closes June 8, reviewed here)

CLOSING SATURDAY OFF BROADWAY:

• Macbeth * (drama, PG-13, unsuitable for children, reviewed here)