Peter Pears sings Schubert’s “Wohin?” (from Die schöne Müllerin) with Benjamin Britten at the piano:

(This is the first in a weekly series of arts-related videos that will appear in this space each Wednesday.)

Archives for May 2008

TT: Almanac

“Cultural conservatism is becoming an older writer: anything else is cosmetics anyway. If he whores after the new thing, he will only get it wrong and wind up praising the latest charlatans, the floozies of the New. His business is keeping his own tradition alive and extending it into its own future: an old writer can grow indefinitely, what he cannot do is keep up.”

Wilfrid Sheed, Essays in Disguise

TT: Bargain basement

Two years ago I wrote a “Sightings” column for The Wall Street Journal in which I described Arnold Friedman, who died in near-obscurity in 1946, as “the greatest artist you’ve never heard of.” I’d been writing about Friedman at odd intervals since 2003, when I made mention in my old “Second City” column for the Washington Post of an exhibition of paintings from the collection of Tommy and Gill LiPuma that included several of his canvases.

One of them, “Still Life (Petunias),” was also included in the Friedman retrospective that was the occasion for my “Sightings” column. It impressed me as much in 2006 as it had three years earlier: “In the foreground is a vase of flowers whose vibrantly colored petals all but burst off the canvas….Hanging on the wall immediately behind the vase is the lower half of an abstract painting–Friedman’s way of underlining the subtle relationship between abstraction and representation. The juxtaposition of the two genres is both witty and thought-provoking, unveiling fresh layers of implication at every glance.”

One of them, “Still Life (Petunias),” was also included in the Friedman retrospective that was the occasion for my “Sightings” column. It impressed me as much in 2006 as it had three years earlier: “In the foreground is a vase of flowers whose vibrantly colored petals all but burst off the canvas….Hanging on the wall immediately behind the vase is the lower half of an abstract painting–Friedman’s way of underlining the subtle relationship between abstraction and representation. The juxtaposition of the two genres is both witty and thought-provoking, unveiling fresh layers of implication at every glance.”

So why haven’t you heard of Friedman? That question was the subject of my “Sightings” column:

Arnold Friedman spent most of his adult life toiling as a postal clerk in Manhattan, painting in his attic after hours. Not long after his death in 1946, Clement Greenberg, the critic who put Jackson Pollock on the map, called Friedman “one of the best painters this country has ever produced,” praising his Post-Impressionist landscapes as “for color and texture…without equal in our time.” Yet even Greenberg’s lavish praise failed to make a dent in his obscurity, and “Arnold Friedman: The Language of Paint,” which opened two weeks ago, is the first large-scale retrospective of his work to be held since 1950.

Where can you see this extraordinary show? The Metropolitan Museum and the Museum of Modern Art both own paintings by Friedman. The permanent collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art is largely devoted to modern painters of his generation. Which of these august New York institutions saw the light? None of them. “Arnold Friedman: The Language of Paint” is on display through June 30 at Hollis Taggart Galleries, right across the street from the Whitney, and several of the finest paintings in the show are for sale.

In recent years a growing number of commercial art galleries in Manhattan have been mounting museum-quality shows devoted to insufficiently appreciated artists of the past….Any museum in town would have been graced by these shows–yet it was left to the galleries to put them on.

Why? One reason is that virtually all of the top American museums have succumbed to a bigger-is-better mentality that leads them to devote huge chunks of their exhibition space to blockbuster shows by popular artists. Just as important, though, are the art-historical “narratives” that curators use to decide how–or whether–they will hang works from their permanent collections.

In the received version of the history of modernism, for instance, it’s taken for granted that American art did not come to maturity until the rise of Abstract Expressionism in the ’40s. Artists who fail to fit neatly into that story line, either because (like Friedman) they came along too soon or preferred to work in a different style, are ignored or pushed off to one side–sometimes literally. Milton Avery, a major American artist who flirted with abstraction but chose not to embrace it, is represented in the Museum of Modern Art by a single canvas, “Sea Grasses and Blue Sea,” hung in a stairwell. It used to hang in the cloakroom….

As for “Arnold Friedman: The Language of Paint,” I’ve seen it twice, and I plan to go back a third time. Among other things, I want to take one last look at Friedman’s “Sawtooth Falls,” a 1945 canvas of the utmost splendor. It’s on loan from the Museum of Modern Art, but I’ve never seen it there, nor do I expect MoMA to hang it any time soon–unless, of course, they can find an empty stairwell.

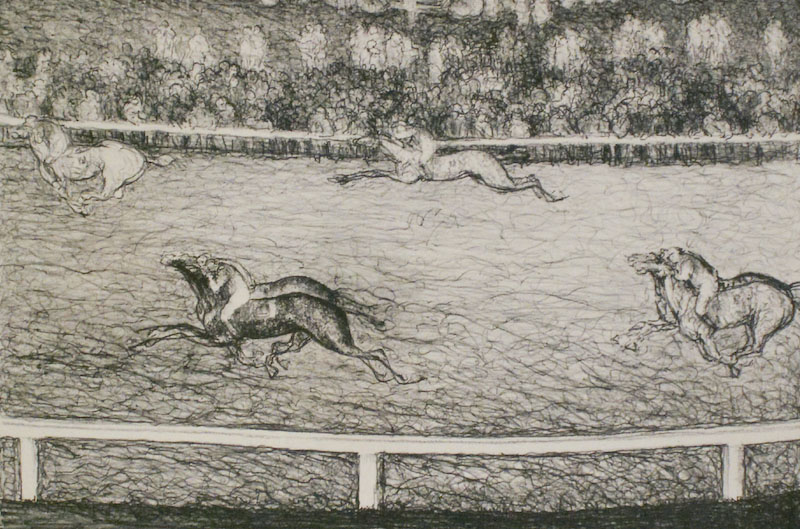

So far as I know, “Sawtooth Falls” has yet to be put on display by MoMA, nor has the Metropolitan Museum of Art ever bothered to hang its lone Friedman, “Unemployable,” at any time since I’ve been going there. But immediately after I wrote my Wall Street Journal column about Friedman, I acquired one of his prints from the Philadelphia Print Shop for the modest price of $225. Last week I bought another, a 1930 lithograph called “Two Polo Players,” from Bloom Fine Art and Antiques. It cost me $240.

Here it is:

Needless to say, I’d like to own one of Friedman’s oil paintings or pastels, but I haven’t got that kind of money to throw around. Fortunately, he was also a superbly gifted printmaker, and “Two Polo Players” fits very nicely into the Teachout Museum.

I pass on this story both to share my delight in my new acquisition and to inspire those of you who long to try your hand at collecting art but suffer from the mistaken notion that you have to be rich to do so. Two hundred and forty dollars for a limited-edition lithograph by a chronically underappreciated American master strikes me as a damned good deal. So what are you waiting for?

TT: Almanac

Doing this I’m

on trial

After that

you are

Arnold Friedman, inscription on back of painting (n.d.)

TT: Waving the flag

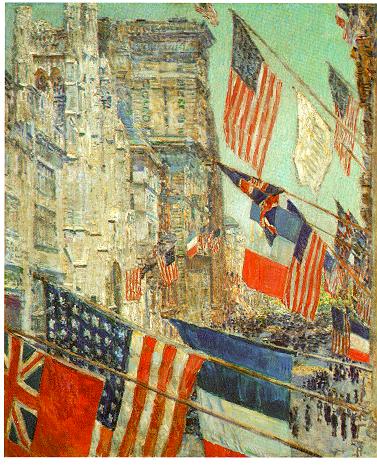

If you’re taking the day off and don’t know why, perhaps this painting, Childe Hassam’s “Allies Day, May 1917,” will remind you. It’s part of a now-celebrated series of paintings on which Hassam embarked after seeing the Preparedness Day parade that took place in New York City on May 13, 1916. “I painted the flag series after we went into the war,” he later recalled. “There was that Preparedness Day, and I looked up the avenue and saw these wonderful flags waving, and I painted the series of flag pictures after that.”

If you’re taking the day off and don’t know why, perhaps this painting, Childe Hassam’s “Allies Day, May 1917,” will remind you. It’s part of a now-celebrated series of paintings on which Hassam embarked after seeing the Preparedness Day parade that took place in New York City on May 13, 1916. “I painted the flag series after we went into the war,” he later recalled. “There was that Preparedness Day, and I looked up the avenue and saw these wonderful flags waving, and I painted the series of flag pictures after that.”

To learn more about Hassam’s flag paintings, go here.

To view a 1932 film of Hassam at work, go here.

TT: Honoris causa

As regular readers of this blog know, I’m a great fan of the crime novels that Donald E. Westlake publishes under the transparent pseudonym of “Richard Stark,” in which he chronicles the capers of a hard-nosed professional burglar known only as Parker who is widely thought to look quite a bit like Lee Marvin:

In addition to choosing Dirty Money, Stark’s latest, as a Top Five pick, I reviewed it admiringly and at greater length here. In that piece I pointed out that most of the early Parker novels are out of print, and that many of them fetch alarmingly high prices on the used-book market.

So it was with great interest that I learned the other day that the University of Chicago Press will be reprinting the first three Parker novels on September 15. The Hunter, The Man With the Getaway Face, and The Outfit will be followed in chronological order by the next thirteen Parker novels, ending with Butcher’s Moon, originally published in 1974. Parker went on a twenty-three-year-long vacation after Butcher’s Moon, returning in 1997 with Comeback. (The post-Comeback novels are all in print.) Says the press release:

So it was with great interest that I learned the other day that the University of Chicago Press will be reprinting the first three Parker novels on September 15. The Hunter, The Man With the Getaway Face, and The Outfit will be followed in chronological order by the next thirteen Parker novels, ending with Butcher’s Moon, originally published in 1974. Parker went on a twenty-three-year-long vacation after Butcher’s Moon, returning in 1997 with Comeback. (The post-Comeback novels are all in print.) Says the press release:

You probably haven’t ever noticed them. But they’ve noticed you. They notice everything. That’s their job. Sitting quietly in a nondescript car outside a bank making note of the tellers’ work habits, the positions of the security guards. Lagging a few car lengths behind the Brinks truck on its daily rounds. Surreptitiously jiggling the handle of an unmarked service door at the racetrack.

They’re thieves. Heisters, to be precise. They’re pros, and Parker is far and away the best of them. If you’re planning a job, you want him in. Tough, smart, hardworking, and relentlessly focused on his trade, he is the heister’s heister, the robber’s robber, the heavy’s heavy. You don’t want to cross him, and you don’t want to get in his way, because he’ll stop at nothing to get what he’s after.

Parker, the ruthless antihero of Richard Stark’s eponymous mystery novels, is one of the most unforgettable characters in hardboiled noir. Lauded by critics for his taut realism, unapologetic amorality, and razor-sharp prose-style–and adored by fans who turn each intoxicating page with increasing urgency–Stark is a master of crime writing, his books as influential as any in the genre. The University of Chicago Press has embarked on a project to return the early volumes of this series to print for a new generation of readers to discover–and become addicted to.

Nicely put.

Amazon is now taking advance orders for The Hunter, The Man With the Getaway Face, and The Outfit. You know what to do. After you’ve done it, go here to read the first lines of all twenty-four Parker novels. This one is my favorite: “When the phone rang, Parker was in the garage, killing a man.”

You can’t get down to business much faster than that.

TT: Almanac

“Everywhere I go I’m asked if I think the universities stifle writers. My opinion is that they don’t stifle enough of them. There’s many a best-seller that could have been prevented by a good teacher. The idea of being a writer attracts a good many shiftless people, those who are merely burdened with poetic feelings or afflicted with sensibility.”

Flannery O’Connor, “The Nature and Aims of Fiction”

DVD

Jacques d’Amboise: Portrait of a Great American Dancer (VAI). This is not a talking-heads documentary lightly sprinkled with fleeting performance snippets, but an anthology of long-lost TV appearances in which one of the foremost male ballet dancers of the Fifties and Sixties can be seen in uncut versions of George Balanchine’s Apollo and Jerome Robbins’ Afternoon of a Faun (dancing opposite the justly legendary Tanaquil LeClercq). Also included are four pas de deux and a rarity, Lew Christensen’s Filling Station, one of the very first ballets on American themes, set to a witty score by Virgil Thomson. The moldering black-and-white kinescopes are a bit on the fuzzy side, but d’Amboise’s charm and athleticism come through with immediate and irresistible clarity (TT).