Two years ago I wrote a “Sightings” column for The Wall Street Journal in which I described Arnold Friedman, who died in near-obscurity in 1946, as “the greatest artist you’ve never heard of.” I’d been writing about Friedman at odd intervals since 2003, when I made mention in my old “Second City” column for the Washington Post of an exhibition of paintings from the collection of Tommy and Gill LiPuma that included several of his canvases.

One of them, “Still Life (Petunias),” was also included in the Friedman retrospective that was the occasion for my “Sightings” column. It impressed me as much in 2006 as it had three years earlier: “In the foreground is a vase of flowers whose vibrantly colored petals all but burst off the canvas….Hanging on the wall immediately behind the vase is the lower half of an abstract painting–Friedman’s way of underlining the subtle relationship between abstraction and representation. The juxtaposition of the two genres is both witty and thought-provoking, unveiling fresh layers of implication at every glance.”

One of them, “Still Life (Petunias),” was also included in the Friedman retrospective that was the occasion for my “Sightings” column. It impressed me as much in 2006 as it had three years earlier: “In the foreground is a vase of flowers whose vibrantly colored petals all but burst off the canvas….Hanging on the wall immediately behind the vase is the lower half of an abstract painting–Friedman’s way of underlining the subtle relationship between abstraction and representation. The juxtaposition of the two genres is both witty and thought-provoking, unveiling fresh layers of implication at every glance.”

So why haven’t you heard of Friedman? That question was the subject of my “Sightings” column:

Arnold Friedman spent most of his adult life toiling as a postal clerk in Manhattan, painting in his attic after hours. Not long after his death in 1946, Clement Greenberg, the critic who put Jackson Pollock on the map, called Friedman “one of the best painters this country has ever produced,” praising his Post-Impressionist landscapes as “for color and texture…without equal in our time.” Yet even Greenberg’s lavish praise failed to make a dent in his obscurity, and “Arnold Friedman: The Language of Paint,” which opened two weeks ago, is the first large-scale retrospective of his work to be held since 1950.

Where can you see this extraordinary show? The Metropolitan Museum and the Museum of Modern Art both own paintings by Friedman. The permanent collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art is largely devoted to modern painters of his generation. Which of these august New York institutions saw the light? None of them. “Arnold Friedman: The Language of Paint” is on display through June 30 at Hollis Taggart Galleries, right across the street from the Whitney, and several of the finest paintings in the show are for sale.

In recent years a growing number of commercial art galleries in Manhattan have been mounting museum-quality shows devoted to insufficiently appreciated artists of the past….Any museum in town would have been graced by these shows–yet it was left to the galleries to put them on.

Why? One reason is that virtually all of the top American museums have succumbed to a bigger-is-better mentality that leads them to devote huge chunks of their exhibition space to blockbuster shows by popular artists. Just as important, though, are the art-historical “narratives” that curators use to decide how–or whether–they will hang works from their permanent collections.

In the received version of the history of modernism, for instance, it’s taken for granted that American art did not come to maturity until the rise of Abstract Expressionism in the ’40s. Artists who fail to fit neatly into that story line, either because (like Friedman) they came along too soon or preferred to work in a different style, are ignored or pushed off to one side–sometimes literally. Milton Avery, a major American artist who flirted with abstraction but chose not to embrace it, is represented in the Museum of Modern Art by a single canvas, “Sea Grasses and Blue Sea,” hung in a stairwell. It used to hang in the cloakroom….

As for “Arnold Friedman: The Language of Paint,” I’ve seen it twice, and I plan to go back a third time. Among other things, I want to take one last look at Friedman’s “Sawtooth Falls,” a 1945 canvas of the utmost splendor. It’s on loan from the Museum of Modern Art, but I’ve never seen it there, nor do I expect MoMA to hang it any time soon–unless, of course, they can find an empty stairwell.

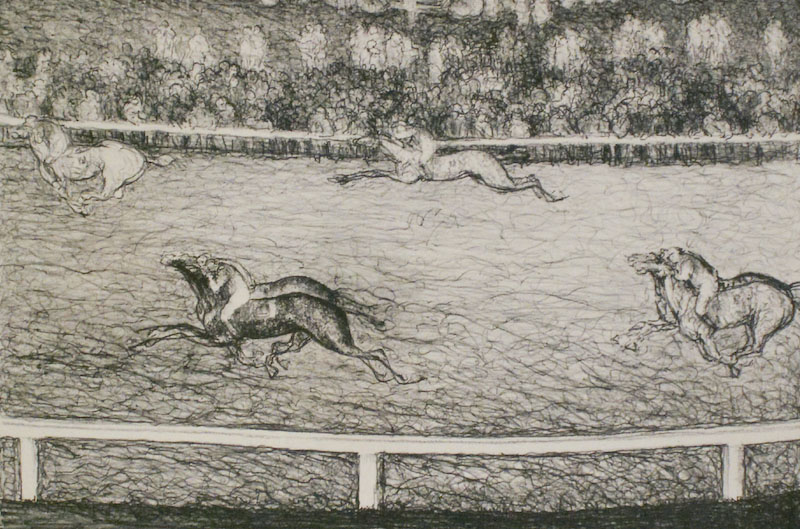

So far as I know, “Sawtooth Falls” has yet to be put on display by MoMA, nor has the Metropolitan Museum of Art ever bothered to hang its lone Friedman, “Unemployable,” at any time since I’ve been going there. But immediately after I wrote my Wall Street Journal column about Friedman, I acquired one of his prints from the Philadelphia Print Shop for the modest price of $225. Last week I bought another, a 1930 lithograph called “Two Polo Players,” from Bloom Fine Art and Antiques. It cost me $240.

Here it is:

Needless to say, I’d like to own one of Friedman’s oil paintings or pastels, but I haven’t got that kind of money to throw around. Fortunately, he was also a superbly gifted printmaker, and “Two Polo Players” fits very nicely into the Teachout Museum.

I pass on this story both to share my delight in my new acquisition and to inspire those of you who long to try your hand at collecting art but suffer from the mistaken notion that you have to be rich to do so. Two hundred and forty dollars for a limited-edition lithograph by a chronically underappreciated American master strikes me as a damned good deal. So what are you waiting for?