Still no Elaine Dundy obituary in the New York Times–or any other newspaper, so far as I know. Don’t these people read blogs? Or books published prior to 1995? Or anything?

Archives for May 6, 2008

TT: Half a loaf

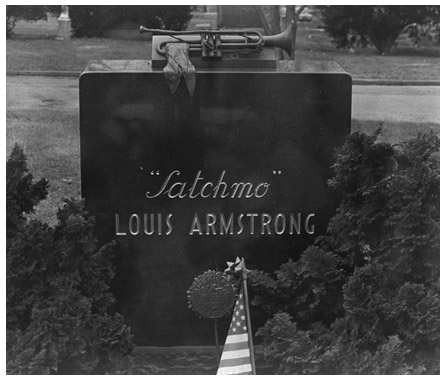

Doing nothing no longer comes naturally to me, but I gave it my best shot yesterday. To be sure, I didn’t spend the whole day doing nothing. I couldn’t–I had a deadline to hit. I got up at seven, wrote and filed my Wall Street Journal drama column, answered my e-mail, and took note of the death of Elaine Dundy. But by noon I was through with the day’s work, so I put on my clothes (yes, I write in dishabille) and strolled over to Columbus Avenue. I caught a cab and told the driver to take me to Danal, where my old friend Rick Brookhiser stood me to a champagne luncheon in honor of the completion of Rhythm Man: A Life of Louis Armstrong.

Doing nothing no longer comes naturally to me, but I gave it my best shot yesterday. To be sure, I didn’t spend the whole day doing nothing. I couldn’t–I had a deadline to hit. I got up at seven, wrote and filed my Wall Street Journal drama column, answered my e-mail, and took note of the death of Elaine Dundy. But by noon I was through with the day’s work, so I put on my clothes (yes, I write in dishabille) and strolled over to Columbus Avenue. I caught a cab and told the driver to take me to Danal, where my old friend Rick Brookhiser stood me to a champagne luncheon in honor of the completion of Rhythm Man: A Life of Louis Armstrong.

“So, what are the first and last words of the book?” Rick asked.

“Ah, the Jane Chord!” I replied.

The Jane Chord, to which Bill Buckley introduced us years ago, is a concept originally promulgated by Hugh Kenner. The idea is that if you make a two-word sentence out of the first and last words of a book, it will tell you something revealing about the book in question. Or not: the Jane Chord of Pride and Prejudice is It/them. But every once in a while you run across a Jane Chord so resonant that it makes the room shiver–the chord for Death Comes for the Archbishop is One/built–and even when a famous book yields up nonsense, it’s still a good game to play.

It had been ages since I’d last struck a Jane Chord, but no sooner did Rick remind me of the rules than I started racking my memory to see if I could recall the chord for Rhythm Man. A moment later I came up with the first and last sentences of the book, and I let out a whoop of delight as I realized that I’d unconsciously put together a humdinger: New/whole.

After lunch I came straight home, curled up on the couch, and spent the next couple of hours listening to Al Cohn and Zoot Sims and rereading Doug Ramsey’s Paul Desmond biography, at which I hadn’t looked since I reviewed it for the Journal three years ago:

You may not know Paul Desmond’s name, but you’ve almost certainly heard his music. He wrote “Take Five,” a sinuous minor-key tune in the once-exotic time signature of 5/4 (marches are in 2/4, waltzes in 3/4, pop songs in 4/4) that was recorded by the Dave Brubeck Quartet in 1959. It shot up the charts a year and a half later, becoming the first jazz instrumental to sell a million copies.

In addition to making its composer rich, “Take Five” also introduced the public at large to the inimitable sound of Desmond’s cool-toned, unsentimentally lyrical alto saxophone playing, which he aptly described as the musical equivalent of a dry martini. In part because of the unexpected popularity of “Take Five,” Brubeck and Desmond became the most famous jazz musicians of the ’60s, and “Time Out,” from which the song was drawn, remains to this day one of jazz’s top-selling albums.

As if being rich and famous weren’t enough, Desmond was also a talented writer of prose (usually in the form of wryly witty liner notes for his solo albums), a preternaturally successful ladies’ man (he preferred fashion models, though he made an exception for the young Gloria Steinem) and a seemingly inexhaustible bon vivant (Elaine’s was his after-hours hangout of choice). He also managed to consume far more than his lifetime quota of cigarettes, alcohol and other, more strictly controlled substances, the combined effect of which presumably contributed to his death from lung cancer in 1977. His friends have been telling tales out of school about him ever since, and one of his closest companions, the jazz critic Doug Ramsey, has now woven the best ones into a biography.

While “Take Five: The Public and Private Lives of Paul Desmond” contains plenty of show-stopping gossip, it is in no way a pathography. Scrupulously researched and written with an attractive combination of affection and candor, it casts a bright light on Desmond’s troubled psyche without devaluing his considerable achievements as an artist. “Any of the great composers of melodies–Mozart, Schubert, Gershwin–would have been gratified to have written what Desmond created spontaneously,” Mr. Ramsey says. Strong words, but “Take Five” makes them stick.

I got so comfy that instead of going out for dinner, I stayed home, ordered a pizza, and watched a movie. I chose Kevin Smith’s Chasing Amy, which I hadn’t seen since shortly after I wrote about it in the New York Times in 1997, back in the long-lost days of innocence when I had only just crossed the fortieth meridian (Shall I part my hair behind? Do I dare to eat a peach?). It’s very much a young man’s film, and the denouement still doesn’t quite parse, but I was pleased to see how well the performances and the rest of the script have held up, and it felt downright luxurious to be able to watch a plot unfold without having to think about how to boil it down into a one-paragraph synopsis.

Watching Chasing Amy put me in mind of the brief gaudy hour when sharp-witted indie and indieish flicks like Clerks, Election, Ghost World, Kicking and Screaming, Living in Oblivion, Metropolitan, Next Stop Wonderland, Panic, Pi, Swingers, and You Can Count on Me seemed to be coming out every month or so. Back then I was writing about movies regularly, and I went so far as to predict in 1999 that the independent film was the wave of the narrative future:

Watching Chasing Amy put me in mind of the brief gaudy hour when sharp-witted indie and indieish flicks like Clerks, Election, Ghost World, Kicking and Screaming, Living in Oblivion, Metropolitan, Next Stop Wonderland, Panic, Pi, Swingers, and You Can Count on Me seemed to be coming out every month or so. Back then I was writing about movies regularly, and I went so far as to predict in 1999 that the independent film was the wave of the narrative future:

Americans under thirty are habituated to the characteristic narrative style of film–it is far more familiar to them than that of prose fiction–and many talented young American storytellers who once might have chosen to write novels are instead making small-scale movies of considerable artistic merit….it is only a matter of time before similar films are routinely released directly to videocassette and marketed like books (or made available in downloadable form over the Internet), thus circumventing the current blockbuster-driven system of film distribution. Once that happens, my guess is that the independent movie will replace the novel as the principal vehicle for serious storytelling in the twenty-first century.

I made that bold prophecy in The Wall Street Journal, then included it in A Terry Teachout Reader five years later. And what happened? I became a drama critic–and I’ve seen exactly two movies in a theater since the fall of 2005. So much for my prescience.

Be that as it may, I enjoyed my nostalgic wallow so much that I briefly considered watching another movie, but in the end I decided not to press my luck. For once I’m going to bed early, I told myself. So I called Mrs. T in Connecticut, then turned off the lights and clambered up the ladder to my loft, feeling as contented as it’s possible for me to feel when she’s there and I’m here.

Now what? Well, I’ve got another Journal column to write this morning, but once it’s done I’m finished until tomorrow. A walk in Central Park? An afternoon nap? The Metropolitan Museum? More Al and Zoot? Call me irresponsible! Why didn’t anybody ever tell me that it’s fun to do nothing?

CAAF: Krook go boom

Remember that point in Bleak House when Krook, the drunken rag-and-bone guy, spontaneously combusts in his shop? In my mind I always related the fatal combustion less to Krook’s drinking than to his oiliness and the general blackness of his soul, as if he were a one-man grease fire lit by his own evil (as it were).

Then a couple weeks ago, Wait Wait… Don’t Tell Me! had a segment on Prohibition, and one of the questions had to do with the claim of early temperance activists that alcohol consumption could lead to spontaneous combustion, the logic being that alcohol burns.* And I thought, “Krook! Krook!”

Sure enough, that’s the folk belief that Dickens drew on to plot Krook’s end. Although, according to this website (be warned: there’s a spooky photograph there that Will Haunt Your Dreams), Dickens maintained that Spontaneous Human Combustion (SHC) wasn’t superstition but fact:

Krook was a heavy alcoholic, true to the popular belief at the time that SHC was caused by excessive drinking. The novel caused a minor uproar; George Henry Lewes, philosopher and critic, declared that SHC was impossible, and derided Dickens’ work as perpetuating an uneducated superstition. Dickens responded to this statement in the preface of the 2nd edition of his work, making it quite clear that he had researched the subject and knew of about thirty cases of SHC. The details of Krook’s death in Bleak House were directly modeled on the details of the death of the Countess Cornelia de Bandi Cesenate by this extraordinary means; the only other case that Dickens actually cites details from is the Nicole Millet account that inspired Dupont’s book about 100 years earlier.

Now, you have to consider any Google search that has already delivered the sentence, “Over the past 300 years, there have been more than 200 reports of persons burning to a crisp for no apparent reason,” as a clear success. But there’s more!** The incidents surrounding the death of the Countess are covered in detail here. Meanwhile, the BBC website sheds light on the other case Dickens mentioned in his preface, Nicole Millet’s death:

However, the first reliable documentation of SHC dates back to 1763 when Frenchman Jonas Dupont compiled a casebook of SHC cases in a book called De Incendiis Corporis Humani Spontaneis, having been compelled by the Nicole Millet case, which involved a man who was acquitted of the murder of his wife when the court ruled that the unfortunate woman’s death had been due to spontaneous combustion.

Nicole Millet was the wife of the landlord of the Lion d’Or in Rheims, who was supposedly found burnt to death in an unburnt chair in February, 1725 (on Whit Monday). Her husband was accused of her murder and arrested; however, a young surgeon named Nicholas le Cat managed to convince the court that her death was caused by SHC. The court ultimately ruled her death as ‘by a visitation of God.’ However, the investigative author Joe Nickell stated in his book, Secrets of the Supernatural, that Millet’s body was not actually found in the chair, but that a portion of her head, several vertebrae and portions of her lower extremities were found on the kitchen floor, the surrounding ground of which had also been burnt. Three accounts were cited: Theodric and John Becks’s Elements of Medical Jurisprudence (1835), George Henry Lewes’s Spontaneous Combustion from Blackwoods Edinburgh Magazine No. 89 (April 1861) and Thomas Stevenson’s Principals and Practice of Medical Jurisprudence (1883). Strangely, there was no mention of Nicholas le Cat.

Emphasis mine.

* Another rationale for the belief, proferred at the BBC website, is that “a body saturated with such combustible fluids would be prone to combustion at the slightest spark.” However, the article continues reassuringly, “the concentration of alcohol in a body would never be high enough for ignition to occur.”

** If this post is tending a little ghoulish, my apologies. I spent most of the summer of 1978 (age 7) suffering from a morbid fear/hope that I might spontaneously combust at any moment after my best friend J. brought up the possibility during a sleepover. So, in addition to clarifying all things Krook, this research was psychologically cathartic.

TT: Almanac

“I once asked Ben Britten what he thought was the most important requisite in composing opera. I was sure he would say a sense of drama, ability to indicate the meaning of a scene musically in a matter of seconds. What he said was that the most important thing a composer must have is the ability to write many kinds of music–chorus alone, chorus with orchestra, soloists separately, soloists in ensemble, and so on. The needs are so varied that one must have terrific facility to handle them all.”

Aaron Copland, Copland Since 1943