• I don’t like most advertising slogans, especially the idiot taglines used to advertise today’s movies (“The bravest place to stand is by each other’s side”). Rarely, though, has a slogan puzzled me more than the one I saw on a Baltimore billboard a couple of weeks ago. It’s the motto of the Baltimore Opera Company: Opera. It’s better than you think. It has to be. I’m not averse on principle to self-deprecation, but why on earth does the BOC think that running down opera will induce people to change their minds about it?

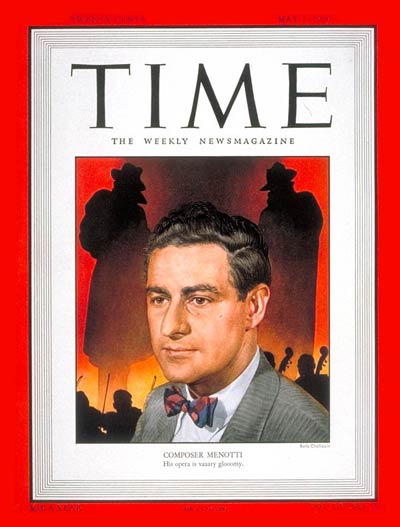

The fact is that when done right, opera is the most immediately exciting of all art forms, one that is more than capable of appealing to a truly popular audience. Paul Moravec and I aren’t writing The Letter for a coterie of sniffish, shiny-domed snobs. We hope to reach the same kind of theatergoers who came to see Gian Carlo Menotti’s The Consul on Broadway in 1950, an event that earned Menotti a cover story in Time. Nor do we think that to be an unrealistic ambition. As Robertson Davies wrote in The Lyre of Orpheus, “Opera speaks to the heart as no other art does, because it is essentially simple.”

The fact is that when done right, opera is the most immediately exciting of all art forms, one that is more than capable of appealing to a truly popular audience. Paul Moravec and I aren’t writing The Letter for a coterie of sniffish, shiny-domed snobs. We hope to reach the same kind of theatergoers who came to see Gian Carlo Menotti’s The Consul on Broadway in 1950, an event that earned Menotti a cover story in Time. Nor do we think that to be an unrealistic ambition. As Robertson Davies wrote in The Lyre of Orpheus, “Opera speaks to the heart as no other art does, because it is essentially simple.”

To be sure, Broadway has changed greatly since 1950, as has Time, but even so, I don’t see why those who are in the business of making opera should feel any need to apologize for their product. Instead, they ought to spread the word that a well-produced opera is thrilling–and accessible. The Letter is about love, sex, vengeance, and death. It contains two murders, both of them bloody. It also contains tunes that you can hum. It is, in short, what my musical collaborator likes to call “a rattling good show,” just like the classic play to which Howard Dietz paid witty tribute in “That’s Entertainment”: Some great Shakespearean scene/Where a ghost and a prince meet/And everyone ends in mincemeat.

That’s my idea of a slogan for an opera company.

• Finally, finally, finally, the Metropolitan Museum has announced “a complete survey–the first in this country in three decades–of the career of Giorgio Morandi, one of the greatest 20th-century masters of still-life and landscape painting in the tradition of Chardin and Cézanne. The exhibition will comprise approximately 110 paintings, watercolors, drawings, and etchings from his early ‘metaphysical’ works to his late evanescent still-lifes, culled mainly from Italian collections formed by Morandi’s friends, either renowned scholars or eclectic collectors.”

• Finally, finally, finally, the Metropolitan Museum has announced “a complete survey–the first in this country in three decades–of the career of Giorgio Morandi, one of the greatest 20th-century masters of still-life and landscape painting in the tradition of Chardin and Cézanne. The exhibition will comprise approximately 110 paintings, watercolors, drawings, and etchings from his early ‘metaphysical’ works to his late evanescent still-lifes, culled mainly from Italian collections formed by Morandi’s friends, either renowned scholars or eclectic collectors.”

I’ve been blogging about Morandi at odd intervals for the past five years, and I even bid on one of his etchings (unsuccessfully, alas) at a Sotheby’s auction, but I’ve never before had the chance to see more than eight of his exquisite paintings at a time. That was in 2004, when Lucas Schoormans Gallery put on a miniature Morandi retrospective that was one of the greatest experiences of my gallery-going life to date.

Here’s what I wrote about it in the Washington Post:

Here’s what I wrote about it in the Washington Post:

The effect of this show is wildly disproportionate to its minuscule size: six oil paintings and two works on paper, all of them still lifes and none in any obvious way imposing. Yet as you look at how the greatest Italian artist of the 20th century painstakingly arranged and rearranged a dozen bottles, bowls and boxes on a table and painted them over and over again, you find yourself whisked out of the grinding noise of everyday urban life and spirited away to a place of intense stillness. It’s as if a soft-spoken man had slipped discreetly into a small room open to the public, whispering life-changing confidences to the fortunate few who visit him there.

What gives Morandi’s paintings their near-inscrutable power? It’s partly the brushwork, at once delicate and forthright, and partly the extreme subtlety with which he varied his narrow palette of colors. I’m no less fascinated by the way in which he pushes himself to the edge of abstraction in so many of his later works. Those homely objects (some of them easily recognizable from canvas to canvas) grow increasingly vaporous, even transparent, as in the 1960 watercolor that is for me the high point of the show.

Though coveted by connoisseurs, Morandi’s tabletop microcosms have never been popular in this country, or anywhere else. None of them is currently hanging in a New York museum (though two exquisite etchings just went on the block at Sotheby’s), nor has Morandi ever been the subject of a full-scale American retrospective. Until last month, Washington was the only city on this side of the Atlantic where you could occasionally see more than one of his paintings at a time: three at the Hirshhorn, two at the Phillips. In addition, several regional museums own individual Morandis–there’s one in Princeton, N.J., for instance, and another in St. Louis–but if you want to see his work in bulk, you pretty much have to go to the Museo Morandi in Bologna, Italy, from which three paintings in this show are on loan.

So it is a boon and a blessing that Lucas Schoormans has put together this tiny, unforgettable exhibition, not for profit (only one of the pieces, a pencil drawing, is for sale) but for love. It’s worth a trip to Manhattan all by itself, and it repays frequent and repeated viewings.

I have no doubt that the same will be true of “Giorgio Morandi, 1890-1964,” which goes up on September 16 and will be on display through December 14. Expect to see me there–often.