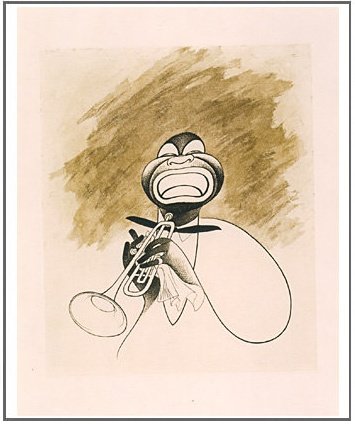

I’m used to being busy, but somehow it failed to occur to me when I agreed two years ago to collaborate with Paul Moravec on The Letter that I might find myself finishing an opera libretto and a book at the same time. Yet that’s what happened, and the time is now. I finished writing the final chapter of Rhythm Man: A Life of Louis Armstrong yesterday afternoon, and Paul is composing the final scene of The Letter. All this is happening at the height of the New York theater season, which means that I’ll be seeing three or four shows a week between now and May 7, the cutoff date after which Broadway shows are no longer eligible for this year’s Tony Awards.

I’m used to being busy, but somehow it failed to occur to me when I agreed two years ago to collaborate with Paul Moravec on The Letter that I might find myself finishing an opera libretto and a book at the same time. Yet that’s what happened, and the time is now. I finished writing the final chapter of Rhythm Man: A Life of Louis Armstrong yesterday afternoon, and Paul is composing the final scene of The Letter. All this is happening at the height of the New York theater season, which means that I’ll be seeing three or four shows a week between now and May 7, the cutoff date after which Broadway shows are no longer eligible for this year’s Tony Awards.

The bad part about being so busy is that I’m occasionally tired enough to fall on my face. The good part is that I haven’t had time to worry about the book, the opera, or anything else. If it’s a virtue to live in the moment–and I’m not so sure it is–then right now I’m the most virtuous guy in New York City. For the past couple of weeks I’ve been getting up, going to work, eating, going back to work, going to bed, then starting over again the next day.

I finished my last book four years ago, on which occasion I had this to say:

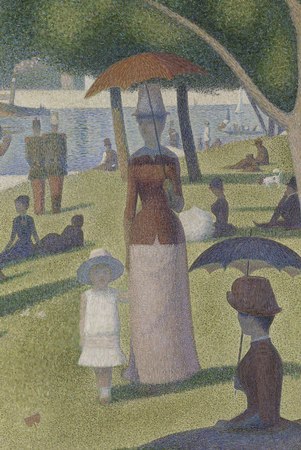

Three months ago, All in the Dances didn’t exist. Over the years I’d told dozens of people all about George Balanchine’s life and work, but every time I had to start fresh. Now there’s an inch-thick pile of paper on my kitchen table with a title page on top, the gateway to a world I made, and even though I’ll be reviewing a Broadway play tomorrow morning, then writing my Washington Post column in the afternoon, part of me is still back in that world of shadows.

Since then I’ve constructed a brand-new world of shadows, and spent large chunks of my waking hours living in it. Most of them have been happy–Satchmo is a very agreeable man with whom to pass your days–but once Santa Fe Opera commissioned The Letter and told Paul and me that they wanted to give the premiere in the summer of 2009, I’ve been tied to a pair of not-quite-parallel tracks. It was around then that Mrs. T and I decided to get married, which added yet another layer of happy complication to my life. So now I’m trying to get used to the fact that once I finish editing and polishing Rhythm Man and deliver the manuscript to Andrea Schulz, my editor at Harcourt, that same life, full though it is, will have a book-sized hole in it.

Four years ago I recalled the lyric to a song by Stephen Sondheim as I wrote the last page of All in the Dances:

Four years ago I recalled the lyric to a song by Stephen Sondheim as I wrote the last page of All in the Dances:

Finishing the hat,

How you have to finish the hat.

How you watch the rest of the world

From a window

While you finish the hat….

Making art–and a biography is a work of art, more or less–is a strange sensation. During your working hours you really do watch the rest of the world from a window, yet at the same time you don’t fully feel the act of creation in which you’re involved. Hours slip by without your being aware of their passing, and all at once you look up and the sun has set. On Wednesday I got up at eight, went to work at eight-thirty, and stopped writing at six-forty-five to dress for the theater, and the only person I spoke to during that time (except for a brief call to Mrs. T in Connecticut at midday) was the waitress from whom I ordered my lunch. When I was done I’d written eight thousand words, the equivalent of eight Wall Street Journal drama columns, yet I barely noticed that I was writing them until I was through. I was thinking about the last eight years of Louis Armstrong’s life and turning my thoughts into words and sentences and paragraphs, and by then I was so deeply immersed in the process of finishing my book that I was all but unconscious of it.

I blogged about this sensation, or lack of it, three years ago:

I write fast. It takes me, for example, two and a half hours to knock out a thousand-word Wall Street Journal drama column (except when I’m sick). This isn’t exactly freakish, but it’s quick enough to stagger many of my friends and colleagues. I can’t explain my facility, so I joke about it, but the fact is that I, too, find it mystifying, though it’s not the speed that puzzles me–it’s that I don’t really know where all those words come from in the first place. On occasion I may spend a few minutes tinkering with a punch line until I hear it go click, and of course I edit and polish the surfaces of my pieces as painstakingly as time permits, but beyond that I have next to no insight into the thought processes that cause them to pour out of my fingers.

It occurs to me that this seeming incomprehension may have something to do with the fact that I am (or was) as much a musician as a writer. Music, after all, is a non-verbal art form, and the only descriptions of the creative experience that ring true to my ear are those of composers. “I am the vessel through which Le Sacre passed,” Igor Stravinsky said of the writing of The Rite of Spring. When I first ran across that remark I thought, That’s exactly how it feels when I write a piece–it passes through me.

Now Rhythm Man has passed through me, and from here on out my involvement with its creation will be conscious. Editing and polishing are acts of which I am entirely aware, and which I find highly pleasurable. I wouldn’t exactly say, by contrast, that writing is pleasurable, any more than breathing is pleasurable. It’s what I do.

The first thing I did after finishing the book, by the way, was back up my hard drive. (Never let it be said that I don’t learn from experience, sometimes.) Then I called Mrs. T in Connecticut, followed by my mother in Smalltown, U.S.A. Then I took a shower and went out to get some dinner. Then I sat around for a couple of hours, pretending to look at a movie. Then I went to bed. Today I have a “Sightings” column to write for Saturday’s Wall Street Journal, after which Mrs. T will be arriving in New York. Yes, we’ll celebrate–and then I’ll get back to work on The Letter. There’s always another hat.