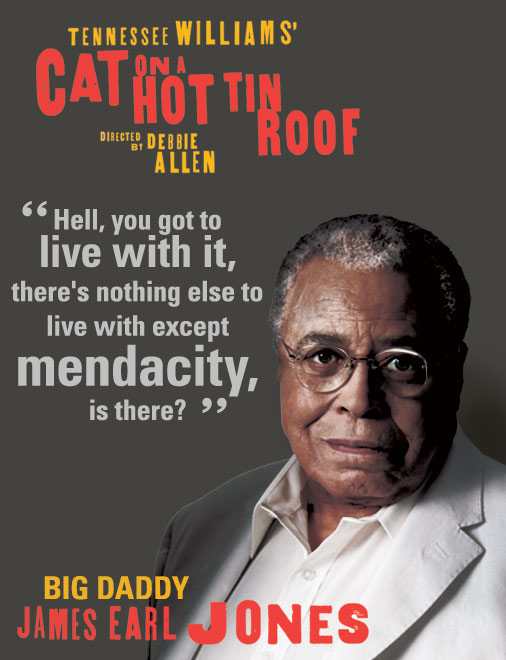

In this morning’s Wall Street Journal I review two New York shows, the all-black Broadway revival of Tennessee Williams’ Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and the New York premiere of Sarah Ruhl’s Dead Man’s Cell Phone. Here’s a sample.

* * *

If you want to behold a great actor giving of his very best, the show to see is “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.” James Earl Jones has turned his back on Broadway in recent years–his last appearance there since the 1987 premiere of “Fences” was in a short-lived 2005 revival of “On Golden Pond,” a synthetic weeper that was unworthy of his towering talent–and so it is a pleasure to welcome him back to town in a role that puts him to the test. Needless to say, Mr. Jones plays Big Daddy, the cancer-ridden plantation owner whose greedy children can barely wait to gobble up his estate, and watching him tear through that giant-sized part is like standing in the path of a cannonball. Alas, you’ll have to pay a high price for the privilege of seeing Mr. Jones strut his stuff, because much of the rest of this unfortunate production borders at times on the downright amateurish.

If you want to behold a great actor giving of his very best, the show to see is “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.” James Earl Jones has turned his back on Broadway in recent years–his last appearance there since the 1987 premiere of “Fences” was in a short-lived 2005 revival of “On Golden Pond,” a synthetic weeper that was unworthy of his towering talent–and so it is a pleasure to welcome him back to town in a role that puts him to the test. Needless to say, Mr. Jones plays Big Daddy, the cancer-ridden plantation owner whose greedy children can barely wait to gobble up his estate, and watching him tear through that giant-sized part is like standing in the path of a cannonball. Alas, you’ll have to pay a high price for the privilege of seeing Mr. Jones strut his stuff, because much of the rest of this unfortunate production borders at times on the downright amateurish.

The amateur-in-chief is Terrence Howard, the erstwhile star of “Hustle & Flow,” who is making his stage debut–not his Broadway debut, mind you, but his stage debut–in the role of Brick, Big Daddy’s favorite son. Mr. Howard is the latest in a long line of inexperienced innocents from Hollywood who have been offered up as burnt sacrifices to the gods of the box office, and the best I can say about his vain attempt to make an impression is that he must have had a lot of nerve to think that he could get away with sharing a curtain call with Mr. Jones….

So far as I know, this is the first all-black professional production of “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” and it’s easy to imagine how well such a concept might have worked had it been executed by a first-rate director. Instead we get Debbie Allen, whose experience at the helm of various sitcoms and musical comedies did not prepare her for the challenge of making sense out of a grossly overwritten melodrama whose verbal extravagance approaches the operatic. Ms. Allen’s way of putting a black spin on “Cat” runs more to such condescendingly on-the-nose directorial details as having a saxophonist wander across the stage at the start of each act, playing hot licks in order to reassure the audience that this production will be racially correct….

Sarah Ruhl writes whimsical, ironic plays about incredibly irritating people. They make me queasy, but her many fans evidently have stronger stomachs. Ms. Ruhl is American theater’s flavor-of-the-month, a playwright whose work is produced all over the country and reviewed with a hushed respect that I once found utterly inexplicable. Then I figured it out: Ms. Ruhl is an arrant sentimentalist who is embarrassed to admit it, so she covers up her old-fashioned tearjerking with a thick sauce of postmodern trickery and tweeness, thus making it palatable to would-be hipsters who are too cool to whip out their hankies….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

An ArtsJournal Blog