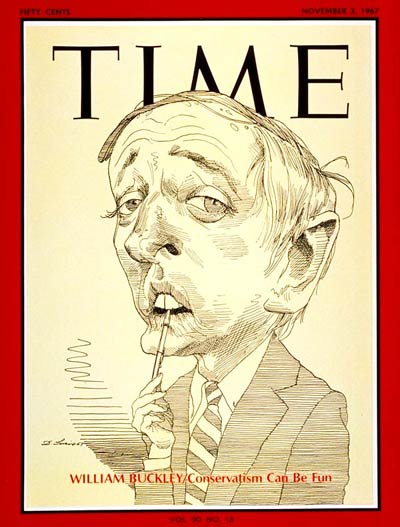

Bill Buckley died this morning. In public life he was a witty, devastatingly effective spokesman for conservatism and the founder of National Review, one of the most influential political magazines of the twentieth century. In private life he was considerate beyond compare, a charismatic host with a magical gift for putting his guests at ease and a passionate amateur pianist who played Bach with fair skill and much love.

Bill Buckley died this morning. In public life he was a witty, devastatingly effective spokesman for conservatism and the founder of National Review, one of the most influential political magazines of the twentieth century. In private life he was considerate beyond compare, a charismatic host with a magical gift for putting his guests at ease and a passionate amateur pianist who played Bach with fair skill and much love.

I had known him since 1981, when he published the first magazine piece I ever wrote, a review of a book about A.J. Liebling. A year later he wrote a syndicated column about another piece of mine, at a time in my life when I was still trying to find myself as a writer, and my path was smoothed by his generous words. On countless other occasions he helped me in ways I knew I would never be able to repay, though I made a token effort by dedicating my Mencken biography to him.

Pat, Bill’s wife, died last April. They had been the closest of companions, and no one who knew him at all well expected him to survive her for long. Nor did he: Bill outlived Pat by less than a year. Now the obituarists will write of his place in the history of postwar American political thought, and they will have much to tell, for he was a very important man and an exceedingly good writer. At some point I will sit down and reread Cruising Speed: A Documentary, my favorite of his five dozen books and the one that best conveys his personality. But not yet: right now I want to think of him not as the great public figure he was but as the charming, funny man who once upon a time was unstintingly kind to an unknown young writer.

I thought the world of him, and I cannot imagine the world without him.

UPDATE: Bill was the friend (though not the pianist) to whom I referred in a posting from 2006:

I’m writing these words immediately after having returned from a private concert held in the art-laden living room of a friend of mine who owns a wonderful old Bösendorfer grand. The performer was a serious amateur pianist who played two Beethoven sonatas, Opp. 109 and 111 (frivolous amateurs don’t play late Beethoven). I sat close enough to the keyboard to read the music over his shoulder. The audience consisted of twenty people, most of whom knew one another more or less well, and after Op. 111 we retired to the host’s dining room for a sit-down meal. That’s the way to hear classical music.

It sure was.