In today’s Wall Street Journal drama column I report on two more of the shows I saw during my recent trip to California, Victory in Hollywood and Blood Knot in San Francisco, plus the Broadway revival of Sunday in the Park with George. Here’s a sample.

* * *

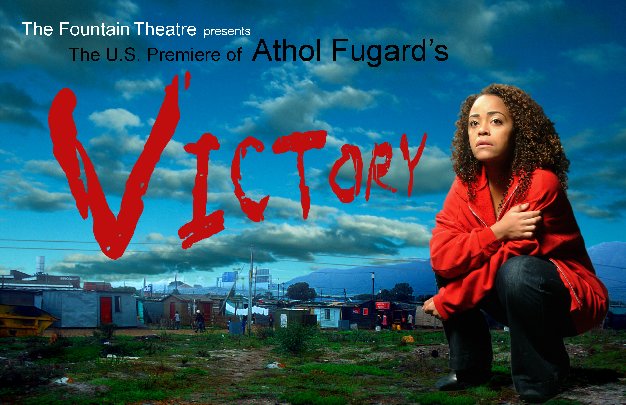

Athol Fugard wondered for a time whether the ending of apartheid in South Africa might also put an end to his playwriting career. Most of his best-known works, starting with “Blood Knot,” the 1961 two-man play that brought him worldwide acclaim, had been set against the brutal backdrop of the racial segregation that the white minority of his native land imposed on its black majority in 1948. Would Mr. Fugard have anything of equal interest to say about the new South Africa brought into being by the demise of apartheid–and would that long-awaited deliverance from evil turn his older plays into stale period pieces? The answers can be found in two productions now playing on the West Coast, the American Conservatory Theater’s San Francisco revival of “Blood Knot” and the American premiere of “Victory,” Fugard’s latest play, which is being presented not on Broadway but in a tiny theater located in–of all places–Hollywood.

Athol Fugard wondered for a time whether the ending of apartheid in South Africa might also put an end to his playwriting career. Most of his best-known works, starting with “Blood Knot,” the 1961 two-man play that brought him worldwide acclaim, had been set against the brutal backdrop of the racial segregation that the white minority of his native land imposed on its black majority in 1948. Would Mr. Fugard have anything of equal interest to say about the new South Africa brought into being by the demise of apartheid–and would that long-awaited deliverance from evil turn his older plays into stale period pieces? The answers can be found in two productions now playing on the West Coast, the American Conservatory Theater’s San Francisco revival of “Blood Knot” and the American premiere of “Victory,” Fugard’s latest play, which is being presented not on Broadway but in a tiny theater located in–of all places–Hollywood.

The Fountain Theatre, one of California’s best drama companies, performs in a 78-seat house whose front row of seats is three feet from the trapezoidal stage. You can’t get much closer than that, and “Victory,” an hour-long play about two angry young blacks (Lovensky Jean-Baptiste and Tinashe Kajese) who break into the home of an aging, demoralized white liberal (Morland Higgins) in the middle of the night, is well served by the miniature scale and fierce concentration of this production, which is supremely well acted by the three-person cast (Ms. Kajese in particular) and staged with relentless intensity by Stephen Sachs, the company’s co-artistic director…

The natural intimacy of a house like the Fountain must necessarily be simulated on the American Conservatory Theater’s large proscenium stage, and one of the things I liked best about that company’s revival of “Blood Knot” was the precision with which Alexander V. Nichols, who designed the set, directs your eye to the pitiful one-room shack at center stage in which the action unfolds. The play itself is a rich character study in which Mr. Fugard passes the adamantine reality of apartheid through the refracting prism of Sartre and Camus to show us two black half-brothers cleaving uncomfortably together in the midst of a hostile world. The setting of “Blood Knot” is by definition political, but what takes place there is intensely, passionately personal, for what interests Mr. Fugard most is not politics but love. “You see, we’re tied together,” the light-skinned Morris (Jack Willis) tells the dark-skinned Zach (Steven Anthony Jones) at play’s end. “It’s what they call the blood knot…the bond between brothers.” A metaphor, yes, but is it essentially public or private? Part of the beauty of “Blood Knot” is that Mr. Fugard doesn’t make you choose.

I found A.C.T.’s 2007 production of “Hedda Gabler” to be competent but ordinary, but there is nothing at all commonplace about “Blood Knot.” Mr. Jones and Mr. Willis dig deeply into their long, difficult roles…

The original Broadway production of “Sunday in the Park with George” ran for 604 performances and won 10 Tonys and a Pulitzer Prize, but the show itself remains one of Stephen Sondheim’s problem children. The first act, a fictionalized re-creation of the making of “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte,” Georges Seurat’s 1886 pointillist masterpiece, is itself a masterpiece of musical theater, a light-textured yet profound parable of the mystery of creation and the self-imposed, single-minded isolation of the creative artist. Not so the second act, in which Mr. Sondheim and James Lapine tell a parallel tale of the modern-day art world that lapses into the same cloying sententiousness that mars the second act of “Into the Woods,” their 1987 fairy-tale musical: Anything you do,/Let it come from you./Then it will be new.

The original Broadway production of “Sunday in the Park with George” ran for 604 performances and won 10 Tonys and a Pulitzer Prize, but the show itself remains one of Stephen Sondheim’s problem children. The first act, a fictionalized re-creation of the making of “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte,” Georges Seurat’s 1886 pointillist masterpiece, is itself a masterpiece of musical theater, a light-textured yet profound parable of the mystery of creation and the self-imposed, single-minded isolation of the creative artist. Not so the second act, in which Mr. Sondheim and James Lapine tell a parallel tale of the modern-day art world that lapses into the same cloying sententiousness that mars the second act of “Into the Woods,” their 1987 fairy-tale musical: Anything you do,/Let it come from you./Then it will be new.

In Sam Buntrock’s London production, which the Roundabout Theatre Company has imported to Broadway for a three-month run, design is the key. David Farley’s bare-walled set serves as the screen for a complex series of digitally animated projections executed by Timothy Bird that seek to simulate the lengthy process by which Seurat’s great painting (which is now one of the glories of the Art Institute of Chicago) came into being. The results, which are spectacular enough to make a Manhattan crowd gasp, add up to the most aesthetically persuasive use of video technology ever to be seen on a Broadway stage. I have no doubt that they will soon be imitated the world over.

On occasion, though, Mr. Bird’s bedazzling visual trickery gets between the actors and the audience, and sometimes I wondered whether so excellent a cast might not have been better served by a less elaborate production. Certainly Daniel Evans, who played George in London and is now repeating the role on Broadway, needs no electronic assistance to animate his part….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

An ArtsJournal Blog