Yesterday I wrote my drama column for Friday’s Wall Street Journal in the morning, then conferred by telephone with Paul Moravec about the fourth scene of The Letter. In the afternoon I finished writing the ninth chapter of Rhythm Man: A Life of Louis Armstrong. I have three chapters to go.

I can’t quite grasp the fact that I knocked off an entire chapter in three days. (It must be Mrs. T’s cooking.) Needless to say, I plan to push on to Chapter 10 at once, but for the moment I feel like celebrating. In case you care to join me, here’s an excerpt from the chapter I just wrote.

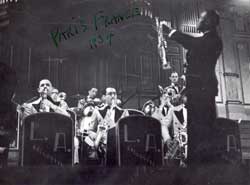

The year is 1937. Armstrong has just signed with a new manager and a new record label, made his feature-film debut in Bing Crosby’s Pennies from Heaven, and become the first black person to host his own variety show on radio. He is now famous, not just in the world of jazz or among his fellow blacks but to the American public at large. This is a brief glimpse of what his life is like.

* * *

Being a star made little difference to Armstrong’s everyday life. He had always been an uncomplaining workhorse, and Joe Glaser, his new manager, worked him harder than ever now that he was starting to make serious money. “Once we jumped from Bangor, Maine, to New Orleans for a one-nighter, then on to Houston, Texas, for the next night,” Pops Foster, Armstrong’s bassist, recalled in his autobiography. He lived in the continuous present, playing pretty for the people, grabbing a bite to eat between shows, signing autographs after the last set, rapping out a dozen letters on his portable typewriter before bedtime, then repeating the cycle the next day. After each dance he peeled off his sweat-drenched clothes and cleaned himself as best he could. “I mean, you see, places did not have them fine dressing rooms and showers and things then,” Charlie Holmes said. “You just waited until everybody got out of the place, and then he could change his clothes after everybody had gone, and dry himself with his own towels and things.” It wasn’t always that rough–sometimes the band traveled by private railroad car–but more often they rode the bus, and Armstrong rode it with them. “He was a hard worker and a hard-workin’ man,” Holmes added, “and he didn’t ask you to do nothin’ that he wouldn’t do.”

Being a star made little difference to Armstrong’s everyday life. He had always been an uncomplaining workhorse, and Joe Glaser, his new manager, worked him harder than ever now that he was starting to make serious money. “Once we jumped from Bangor, Maine, to New Orleans for a one-nighter, then on to Houston, Texas, for the next night,” Pops Foster, Armstrong’s bassist, recalled in his autobiography. He lived in the continuous present, playing pretty for the people, grabbing a bite to eat between shows, signing autographs after the last set, rapping out a dozen letters on his portable typewriter before bedtime, then repeating the cycle the next day. After each dance he peeled off his sweat-drenched clothes and cleaned himself as best he could. “I mean, you see, places did not have them fine dressing rooms and showers and things then,” Charlie Holmes said. “You just waited until everybody got out of the place, and then he could change his clothes after everybody had gone, and dry himself with his own towels and things.” It wasn’t always that rough–sometimes the band traveled by private railroad car–but more often they rode the bus, and Armstrong rode it with them. “He was a hard worker and a hard-workin’ man,” Holmes added, “and he didn’t ask you to do nothin’ that he wouldn’t do.”

Few survivors of the big-band era have been inclined to romanticize the rigors of life on the road. Charlie Barnet summed it up in six devastatingly well-chosen words: “You stay tired, dirty and drunk.” The trombonist Mike Zwerin, who toured with Claude Thornhill in the Fifties, was more expansive about its horrors: “You skim more than read, pass out rather than fall asleep. You work when everybody else is off, breakfast in the evening, dinner at dawn. Disorder is the order, physical alienation is so powerful, so omnipresent, that no treatment seems to extreme. Nobody can even question the need for treatment. Playing chess will not do the trick. You’ve got to find a familiar internal place to hang on to, it’s a matter of survival. And there is one place, a warm corner called stoned.” Armstrong curled up in that corner most nights, though he was disciplined in his use of marijuana, his drug of choice. “He never worked with it,” said one of his sidemen. “He’d wait until he got off and get with his typewriter and hunt and peck jokes. When he’d write someone a letter, that would be his letter. He’d send them a joke….Write jokes every night. Get off of work, put some salve on his lips, handkerchief on his head.”

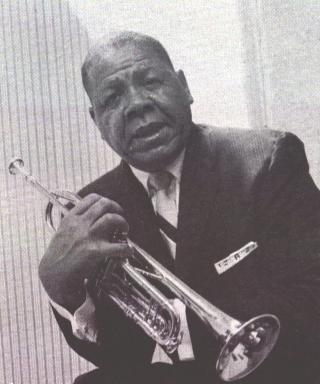

It was no way to live, but the trumpeter knew no other, and he appeared by all accounts to thrive on it. His playing, according to Charlie Holmes, was better than ever: “Other trumpet players would hit them [high] notes, just like they do nowadays. They’d be hitting high notes, but they sound like a flute up there or something. But Louis wasn’t playing them like that. Louis was hittin’ them notes right on the head, and expanding. They would be notes. He was hittin’ notes. He wasn’t squeakin’. They wasn’t no squeaks. They were notes. Big, broad notes. And nobody had never heard no trumpet player like that before….The higher he went, the broader his tone got–and it was beautiful!”

But even Armstrong had his limits, and Glaser, unlike his predecessor, was smart enough to recognize them. In 1937 he hired J.C. Higginbotham and Henry “Red” Allen, both of whom had graced Luis Russell’s group back in the days when it was known as one of the hottest bands in Harlem. Allen, a fellow New Orleans expatriate and alumnus of Fate Marable’s floating conservatory who had, like Armstrong, worked with Joe Oliver and Fletcher Henderson, was a hugely imaginative trumpet soloist with a knack for making harmonically “wrong” notes sound right. Not only had he recorded with Armstrong back in 1930, but the two men had even split a chorus on “I Ain’t Got Nobody,” interweaving their styles so seamlessly that few could (or can) tell them apart. Glaser hired Allen to be Armstrong’s relief man, a role he played so well that he would be billed as “LOUIS ARMSTRONG’S UNDERSTUDY.”

But even Armstrong had his limits, and Glaser, unlike his predecessor, was smart enough to recognize them. In 1937 he hired J.C. Higginbotham and Henry “Red” Allen, both of whom had graced Luis Russell’s group back in the days when it was known as one of the hottest bands in Harlem. Allen, a fellow New Orleans expatriate and alumnus of Fate Marable’s floating conservatory who had, like Armstrong, worked with Joe Oliver and Fletcher Henderson, was a hugely imaginative trumpet soloist with a knack for making harmonically “wrong” notes sound right. Not only had he recorded with Armstrong back in 1930, but the two men had even split a chorus on “I Ain’t Got Nobody,” interweaving their styles so seamlessly that few could (or can) tell them apart. Glaser hired Allen to be Armstrong’s relief man, a role he played so well that he would be billed as “LOUIS ARMSTRONG’S UNDERSTUDY.”

Armstrong featured Allen extensively at his public appearances. “Louis gave Red an hour’s time on his own, to play his own numbers….Red could do anything he wanted to play,” Charlie Holmes said. In the recording studio, by contrast, Allen stuck exclusively to ensemble parts–he only recorded one solo with the Armstrong band–but that was fine with him. “It was no fault of Louis’, and I played plenty with the band,” he recalled. “It was a happy feeling. I don’t care whose band it was, I’d have been happy about it if Louis was there, because I enjoy being in his company so much, on and off the bandstand.”

Armstrong was glad to have him there, too. At the age of thirty-six he was learning at last how to burn the bright candle of his talent at one end, and for the rest of his life he would take care to make room on the bandstand for musicians who could help him carry the load without stealing the show out from under him….

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City