In today’s Wall Street Journal drama column I return to New York to review two shows which could scarcely be more different, Disney’s The Little Mermaid and Samuel Beckett’s Happy Days. Here’s a sample.

* * *

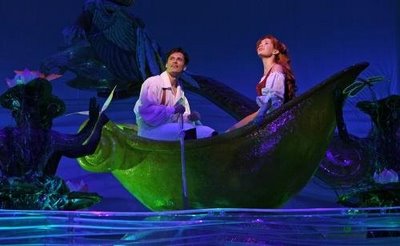

Rumors of doom have stalked “The Little Mermaid” ever since its Denver tryout last August, and the whispers grew louder as it swam toward Broadway. So let me start off by answering the big question: The new Disney musical is a charmer. No, it’s not “Return of the Lion King,” but “The Little Mermaid” passes the ooh-and-aah test with plenty of room to spare. Unlike the inexplicably grumpy “Mary Poppins,” “Mermaid” is both visually ingenious and emotionally satisfying, and I expect it to run from here to eternity and back again.

Based on the much-loved 1989 animated feature that breathed new life into the cartoon trade, “The Little Mermaid” is a sugar-sparkled retelling of Hans Christian Andersen’s darkly ironic fairy tale about a mermaid with a wandering eye who falls for a human prince and trades her tail and voice for a pair of legs so that she can woo him. In the Disney version, Ariel (Sierra Boggess) gets the guy (Sean Palmer) and lives happily ever after, though not before running afoul of Ursula (Sherie Rene Scott), a scene-stealing octopus who collects “poor unfortunate souls” and wants to put Ariel’s on her shelf.

Based on the much-loved 1989 animated feature that breathed new life into the cartoon trade, “The Little Mermaid” is a sugar-sparkled retelling of Hans Christian Andersen’s darkly ironic fairy tale about a mermaid with a wandering eye who falls for a human prince and trades her tail and voice for a pair of legs so that she can woo him. In the Disney version, Ariel (Sierra Boggess) gets the guy (Sean Palmer) and lives happily ever after, though not before running afoul of Ursula (Sherie Rene Scott), a scene-stealing octopus who collects “poor unfortunate souls” and wants to put Ariel’s on her shelf.

All this is vastly easier to tell–or draw–than it is to put on stage. To start with, how do you turn that stage into a seaful of swimming fish? Choreographer Stephen Mear solved part of the problem by equipping the underwater members of the cast with Heelys, the popular sneakers with wheels built into the heels, thus allowing them to glide instead of walking. Add to this the long-finned costumes of Tatiana Noginova, the fantastically elaborate sets of George Tsypin and the subaqueous rear projections of Sven Ortel and you get a nonliteral evocation of marine life that is not merely plausible but downright uncanny. Forget the kids: I oohed and aahed like a six-year-old as Ariel floated upward to the ocean’s surface and turned into a human….

Written in 1961, “Happy Days” is among the starkest of Samuel Beckett’s theatrical parables about the human condition. Despite its author’s reputation for impenetrability, the symbolism of this two-hander is as intelligible as a kidney punch. The first act is a near-monologue by Winnie (Fiona Shaw), a woman of a certain age who is buried up to her waist in a mound of dirt. Willie (Tim Potter), her husband and audience of one, is a half-demented older man who leaves most of the talking to Winnie. In the second act Winnie is buried up to her chin and Willie is reduced to grunting…

Written in 1961, “Happy Days” is among the starkest of Samuel Beckett’s theatrical parables about the human condition. Despite its author’s reputation for impenetrability, the symbolism of this two-hander is as intelligible as a kidney punch. The first act is a near-monologue by Winnie (Fiona Shaw), a woman of a certain age who is buried up to her waist in a mound of dirt. Willie (Tim Potter), her husband and audience of one, is a half-demented older man who leaves most of the talking to Winnie. In the second act Winnie is buried up to her chin and Willie is reduced to grunting…

Beckett leaves it up to the viewer to draw his own conclusions about the meaning of “Happy Days.” I wish Deborah Warner, the director, had been as willing to leave its symbols completely open, but instead she has ignored the stage directions and set the play in the middle of what looks rather too much like a building that has been leveled by a bomb. (Cliché! Cliché!) Ms. Shaw’s interpretation of the first act is similarly over-explicit–she treats Beckett’s chiseled lines like a series of acting exercises–but once her torso is buried under the rubble, forcing her to act with her voice and face alone, she snaps into tight focus and escorts us to the edge of the abyss….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City