Why do the reputations of some artists go into eclipse immediately after their deaths, while others leave obscurity behind and become household names? In this week’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column, I take a look at what I call the Death Effect, and consider its wide-ranging impact on the posthumous reputations of Béla Bartók, George MacDonald Fraser, Oscar Peterson, and Johannes Vermeer.

To find out more, pick up a copy of the Saturday Journal and turn to the “Weekend Journal” section, or go here to read my column online.

Archives for January 2008

CAAF: Loose notes

“He had come from Rome. ‘Oh, Rome?’ she exclaimed. ‘How lovely!’

He shrugged: ‘Too many nice people.’

She was surprised. He reflected on Roman society, but had enjoyed himself. Though not, evidently, a son of the Church, he was on the warmest of terms with it; prelates and colleges flashed through his talk, he spoke with affection of two or three cardinals; she was left with a clear impression that he had lunched at the Vatican. As he talked, antiquity became brittle, Imperial columns and arches like so much canvas. Mark’s Rome was late Renaissance, with a touch of the slick mundanity of Vogue. The sky above Rome, like the arch of an ornate altar-piece, became dark and flapping with draperies and august conversational figures. Cecilia — whose personal Rome was confined to one mildish Bostonian princess and her circle, who spent innocent days in the Forum displacing always a little hopefully a little more dust with the point of her parasol, who sighed her way into churches and bought pink ink-tinted freezias at the foot of the Spanish steps — could not but be impressed.”

Elizabeth Bowen, To the North

CAAF: And I am Marie of Roumania.

Not to be the autocrat at the kitchen table but I hope at least some of you will watch the PBS production of Northanger Abbey this Sunday night. I’ll be on the couch, in my cardigan with the Kleenex-stuffed sleeves, and it’d be nice to think there are others out there doing the same, like a thousand points of cat ladies. If they managed to make something so interestingly loopy out of a source as quiet and bittersweet as Persuasion I can’t wait to see what gets done with Northanger Abbey, which is already a little schizophrenic as novels go.

Also on the decree front: Last night I was rattling around the house looking for a vampire novel. (We raged a little hard for Mr. Tingle’s birthday on Wednesday night and I spent most of yesterday feeling like Charles Bukowski. Like, my kingdom for a fried-egg sandwich.) No hidden caches of vampire novels revealed itself, so I picked up To The North by Elizabeth Bowen instead. I’m not all that far in but I already want to order everyone in the world to read it too. I had some misguided idea that I wouldn’t like Bowen’s novels, that they’d be too glassy or formal. But they’re not, or at least this one isn’t. Just beautiful.

BOOK

William Maxwell, Early Novels and Stories (Library of America, $35). At last–at last!–the Library of America brings out the first in a pair of volumes devoted to the writings of the New Yorker editor who in his spare time produced some of America’s most lyrical and poignant fiction. Maxwell was never widely recognized in his lifetime, nor is he well known now, but connoisseurs covet his books with obsessive passion. (Don’t take my word for it–read this.) Start with The Folded Leaf, his exquisitely sensitive 1945 novel of adolescent friendship, and go from there (TT).

TT: Funny man gets serious

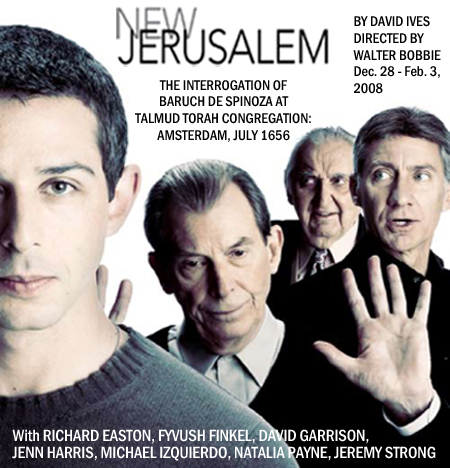

I review three plays in this week’s Wall Street Journal drama column, all in New York and all worth seeing: New Jerusalem, November, and Alfred Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps. Here’s a sample.

* * *

David Ives, the highbrow clown who writes explosively funny one-act plays about eggheads like Philip Glass and Leon Trotsky, has now given us a deadly serious two-act play about a 17th-century philosopher–and it’s good. “New Jerusalem,” in which Mr. Ives grapples with matters of life, death and the hereafter, is so disciplined and persuasive a piece of work that it makes me wonder whether the much-praised author of “Polish Joke” and “All in the Timing” might actually have his best days ahead of him.

David Ives, the highbrow clown who writes explosively funny one-act plays about eggheads like Philip Glass and Leon Trotsky, has now given us a deadly serious two-act play about a 17th-century philosopher–and it’s good. “New Jerusalem,” in which Mr. Ives grapples with matters of life, death and the hereafter, is so disciplined and persuasive a piece of work that it makes me wonder whether the much-praised author of “Polish Joke” and “All in the Timing” might actually have his best days ahead of him.

The long subtitle of Mr. Ives’ play, “The Interrogation of Baruch de Spinoza at Talmud Torah Congregation: Amsterdam, July 27, 1656,” is fair warning to casual theatergoers that the laughter in “New Jerusalem,” while not nonexistent, will be comparatively scarce. If you passed Philosophy 101, you’ll recall that the author of “Tractatus Theologico-Politicus” was a pantheistic skeptic who at the far-from-ripe age of 23 was excommunicated by his co-religionists for promulgating the “abominable heresies” summed up three centuries later by Albert Einstein: “I believe in Spinoza’s God who reveals himself in the orderly harmony of what exists, not in a God who concerns himself with the fates and actions of human beings.” Nothing, however, is known of the trial that brought about Spinoza’s expulsion from Talmud Torah save for the formal writ proclaiming his guilt. In the near-complete absence of concrete information about the proceedings, Mr. Ives has cooked up a courtroom drama of his own devising in which the arrogant young philosopher (Jeremy Strong) and the chief rabbi of Amsterdam (Richard Easton) wrestle passionately with the ever-contemporary problem of faith….

Mr. Ives’ Spinoza is not a sober-sided thinker but a smug, immature young punk who revels in his own genius (“I do know a few things about God that nobody else does”). By choosing not to portray his hero heroically, Mr. Ives throws the viewer off balance and ups the dramatic ante several notches. He also takes care to leaven his script with pinches of black humor…

David Mamet is out to amuse in “November,” his new play about a president (Nathan Lane) whose fathomless cynicism is matched only by his feckless incompetence. “Romance,” Mr. Mamet’s previous venture into knock-down-drag-out comedy, was funnier, but “November” contains plenty of triphammer punchlines. (Asked to name his price for a political favor, the Chief Executive replies, “I want a number so high even dogs can’t hear it.”) Though Mr. Lane is in the wrong show–his acting is too fussy–he gets his laughs anyway, mainly through sheer determination…

If it’s pure fluff you crave, the Roundabout Theatre Company delivers the goods with “Alfred Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps,” a silly sendup of Hitchcock’s witty 1935 film version of John Buchan’s 1915 thriller. This piece of English toffee is performed by a hard-working cast of four, and much of the fun arises from the fact that two of the actors, Arnie Burton and Cliff Saunders, play most of the parts, changing hats and hurling themselves around the stage with mad abandon. The spoofery, which runs to inch-thick accents, who’s-on-first dialogue and nudge-nudge references to other Hitchcock films, is decidedly collegiate…

If it’s pure fluff you crave, the Roundabout Theatre Company delivers the goods with “Alfred Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps,” a silly sendup of Hitchcock’s witty 1935 film version of John Buchan’s 1915 thriller. This piece of English toffee is performed by a hard-working cast of four, and much of the fun arises from the fact that two of the actors, Arnie Burton and Cliff Saunders, play most of the parts, changing hats and hurling themselves around the stage with mad abandon. The spoofery, which runs to inch-thick accents, who’s-on-first dialogue and nudge-nudge references to other Hitchcock films, is decidedly collegiate…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

TT: Almanac

“A speech or an essay may be eloquent, but if it is, the eloquence is incidental to its aim. Eloquence, as distinct from rhetoric, has no aim: it is a play of words or other expressive means. It is a gift to be enjoyed in appreciation and practice. The main attribute of eloquence is gratuitousness: its place in the world is to be without place or function, its mode is to be intrinsic. Like beauty, it claims only the privilege of being a grace note in the culture that permits it.”

Denis Donoghue, On Eloquence

OGIC: Great expectations

Who remembers Jayne Anne Phillips? In high school, in the heyday of my fiction-writing ambitions, I became just possessed by her short stories in the collection Black Tickets. I could recite whole paragraphs of the stuff, which to my teenaged ear had at once a daring, quickening urgency and a quicksand sensuality that could bind you to a word at a time. The story that particularly impressed me was the title story, which starts: “Jamaica Delilah, how I want you; your smell a clean yeast, a high white yogurt of the soul.” This, I thought, was how I wanted to write. Go ahead, laugh. I can take it.

Times change, and so do teenagers. I haven’t thought about Jayne Anne Phillips in many years, but the bits of her prose I remember don’t sound at all like what I’d like to write, if I were still writing fiction; to my adult ear, after a long evolution of taste, they sound for the most part pretentious and a little silly. But I wasn’t alone in embracing them. A copy of Phillips’s later story collection, Fast Lanes, recently turned up in a used bookstore and I picked it up out of curiosity and nostalgia. Its jacket boasts some pretty heady praise for her previous books (Black Tickets and her novel Machine Dreams) from some pretty powerful literary arbiters.

Robert Stone said “Machine Dreams in its wisdom and its compassionate, utterly unsentimental rendering of the American condition will rank as one of the great books of this decade.” Our old friend Michiko Kakutani, writing when still a wunderkind, offered that the novel “will doubtless come to be seen as both a remarkable novelistic debut and an enduring literary achievement.” As for Black Tickets, it is called “the unmistakable work of early genius trying her range” (Tillie Olsen) and “unlike any [stories] in our literature” (Raymond Carver). Nadine Gordimer pronounced her “the best short-story writer since Eudora Welty.”

Now, I haven’t reread Phillips, and any of this may be true. And of course we all know that praise in blurbs and book reviews is chronically overinflated. But it’s striking how enormous the claims are in these plaudits, and how very little one hears Phillips discussed today, just a few decades later. She just doesn’t seem to be part of the conversation, though she must have influenced some of the writers we do talk about. Without the benefit of rereading her, which I may try to do when I finish the book I’m reading now (Rabbit, Run, if you want to know), it’s impossible to say whether she was simply a less prodigious talent than the critics and writers (some of them doubtless her teachers) thought they were beholding or whether Phillips’s timing was unlucky, her style soon outmoded as literary taste changed. Who’s to say that in another thirty years she won’t be rediscovered and newly embraced by a new generation of readers, a la Dawn Powell?

As it happens, JL has been considering similar stories in the visual arts over at Modern Kicks: “It’s a familiar enough story: an artist seemingly poised for fame finds the aesthetic winds changing and her formerly-lauded work out of favor,” he writes of the painter Sonia Gechtoff, reminding us that failures like hers and Phillips’s to fulfill the promise attached to them aren’t always really failures at all.

TT: So you want to see a show?

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

Warning: Broadway shows marked with an asterisk were sold out, or nearly so, last week.

BROADWAY:

• August: Osage County (drama, R, adult subject matter, extended through Apr. 13, reviewed here)

• Avenue Q * (musical, R, adult subject matter and one show-stopping scene of puppet-on-puppet sex, reviewed here)

• A Chorus Line (musical, PG-13/R, adult subject matter, reviewed here)

• The Farnsworth Invention (drama, PG-13, reviewed here)

• Grease (musical, PG-13, some sexual content, reviewed here)

• Grease (musical, PG-13, some sexual content, reviewed here)

• The Homecoming (drama, R, adult subject matter, closes Apr. 13, reviewed here)

• Is He Dead? (farce, G, reasonably family-friendly, reviewed here)

• The Little Mermaid * (musical, G, entirely suitable for children, reviewed here)

• Rock ‘n’ Roll (drama, PG-13, way too complicated for kids, closes Mar. 9, reviewed here)

• The Seafarer (drama, PG-13, adult subject matter, reviewed here)

OFF BROADWAY:

• The Devil’s Disciple (drama, G/PG-13, not suitable for children, closes Feb. 10, reviewed here)

• The Fantasticks (musical, G, suitable for children old enough to enjoy a love story, closes Feb. 24, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON:

• Happy Days (drama, PG-13, too complicated for kids, closes Feb. 2, reviewed here)

CLOSING SUNDAY:

• The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee (musical, PG-13, mostly family-friendly but contains a smattering of strong language and a production number about an unwanted erection, reviewed here)

CLOSING SUNDAY IN MILWAUKEE:

• The Norman Conquests (comic trilogy, PG-13, adult subject matter, reviewed here)