I recently wrote about Harry Haskell’s Boss-Busters and Sin Hounds, a history of the Kansas City Star. One of the passages that struck me most forcibly was this description of how William Rockhill Nelson, the paper’s founder, oversaw its coverage of his own death:

Nelson’s obituary consumed two full pages of the April 13 edition. Autocratic to the last, the famously publicity-shy editor had made sure it said no less–and no more–than he wanted it to say. Mostly written by Ralph Stout, Henry Haskell, and A.B. Macdonald, the editor’s death notice had been set in type weeks earlier and brought to Oak Hall for Nelson’s approval.

H.L. Mencken, by contrast, did what he could to keep his obituary short and to the point, tucking the following note into his clip file in the morgue of the Baltimore Sun: “Save in the event that the circumstances of my death make necessary a news story it is my earnest request to my old colleagues of the Sunpapers that they print only a brief announcement of it, with no attempt at a biographical sketch, no portrait, and no editorial.”

H.L. Mencken, by contrast, did what he could to keep his obituary short and to the point, tucking the following note into his clip file in the morgue of the Baltimore Sun: “Save in the event that the circumstances of my death make necessary a news story it is my earnest request to my old colleagues of the Sunpapers that they print only a brief announcement of it, with no attempt at a biographical sketch, no portrait, and no editorial.”

Not surprisingly, the Sun‘s most celebrated staffer didn’t get his wish. As I wrote in The Skeptic, my Mencken biography:

Some imperatives, however categorical, are meant to be ignored, and the editors of the Sun brushed this one aside without a second thought. The main story in Monday’s paper broke the news simply: “Henry Louis Mencken, newspaper man, critic, wit and Baltimore’s best-known writer, died early yesterday in his sleep at his house on Hollins street.” But it was accompanied by a two-column portrait (in which Mencken, as was his wont when posing for formal photographs, contrived to look puzzled) and a page-one obituary by Hamilton Owens that ended on a personal note: “This is not the place or the time for any final appraisal of H.L. Mencken’s contribution to the culture of the United States. But whatever the conclusions of the students of such things, his colleagues on THE SUN had the benefit, over many years, of association with one of the most stimulating personalities of their time.”

I used to admire Mencken’s determination to avoid that kind of retrospective fanfare, but I’ve since changed my mind. It was, I now believe, a peculiarly twisted kind of vanity: he knew perfectly well that he was going to get the hats-off treatment, and arranged it so that posterity would marvel at his modesty. I no longer find that kind of inverted posturing attractive. As Golda Meir is supposed to have said to someone who played the same card in her presence, “Don’t be so modest–you’re not that great.”

Newspapers take care of their own, so I suppose I’ll be treated to a shortish obituary when the time comes (and no, I’m not anticipating its early arrival). Presumably its author will mention my longstanding relationships with The Wall Street Journal and Commentary, my books, my collaboration with Paul Moravec on The Letter, my profoundly happy marriage to Mrs. T, and–I hope–this blog. Beyond that I doubt there’ll be any personal details, nor should there be: I’m not famous and don’t expect to become so between now and then. Nor am I witty enough to come up with a self-penned epitaph as irresistibly quotable as the one Mencken left behind: “If, after I depart this vale, you ever remember me and have thought to please my ghost, forgive some sinner and wink your eye at some homely girl.”

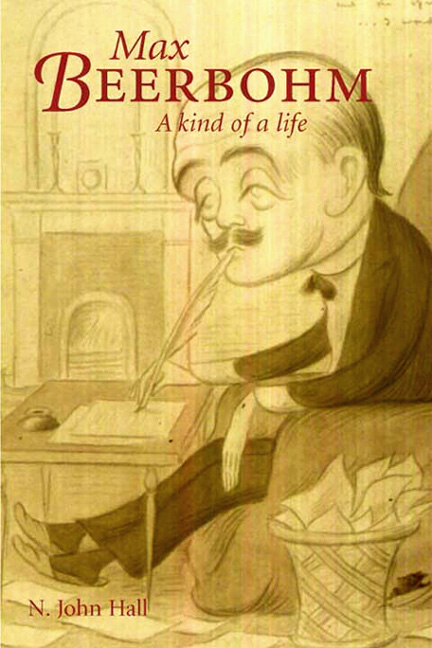

But no matter what gets published about me on the day after the Distinguished Thing comes to call, this much is certain: I won’t read it. Unless you happen to own a newspaper, you don’t get to read your own obituary. And that’s probably as it should be. I’ve written some pretty sharp remarks about the recently deceased, after all, and I wouldn’t be surprised if somebody remembered them when my own time comes–or maybe not. Perhaps I’ll outlive my own minor renown and be remembered solely, as I once speculated in this space, for having owned a Max Beerbohm caricature. Would I want to know that now? Not really. I have a pretty good sense of irony, but I’m not sure it’s that robust.

Which reminds me that Beerbohm himself once wrote a wickedly funny short story called Enoch Soames about an obscure Victorian poet who sold his soul to the devil in return for a chance to peer into the future and see what the readers of the next century would think of his work. Soames jumped into Satan’s time machine, set the controls for June 3, 1997, went straight to the reading room of the British Museum, and looked himself up in a volume called Inglish Littracher 1890-1900. (It seems that England in 1997 had succumbed to the blight of simplified phonetic spelling.) This is what it said:

Which reminds me that Beerbohm himself once wrote a wickedly funny short story called Enoch Soames about an obscure Victorian poet who sold his soul to the devil in return for a chance to peer into the future and see what the readers of the next century would think of his work. Soames jumped into Satan’s time machine, set the controls for June 3, 1997, went straight to the reading room of the British Museum, and looked himself up in a volume called Inglish Littracher 1890-1900. (It seems that England in 1997 had succumbed to the blight of simplified phonetic spelling.) This is what it said:

Fr egzarmpl, a riter ov th time, naimed Max Beerbohm, hoo woz stil alive in th twentith senchri, rote a stauri in wich e pautraid an immajnari karrakter kauld “Enoch Soames”–a thurd-rait poit hoo beleevz imself a grate jeneus an maix a bargin with th Devvl in auder ter no wot posterriti thinx ov im! It iz a sumwot labud sattire, but not without vallu az showing hou seriusli the yung men ov th aiteen-ninetiz took themselvz. Nou that th littreri profeshn haz bin auganized az a departmnt of publik servis, our riters hav found their levvl an hav lernt ter doo their duti without thort ov th morro. “Th laibrer iz werthi ov hiz hire” an that iz aul. Thank hevvn we hav no Enoch Soameses amung us to-dai!

Poor Enoch. Some things are better left unread.

* * *

Here’s a deliciously straight-faced parody of a nonexistent book called Enoch Soames: The Critical Heritage.