The Seafarer (Booth, 222 W. 45). What’s the Broadway show to see if you’re only seeing one? I strongly recommend Conor McPherson’s uncommonly powerful fantasy about an unhappy Irishman (David Morse) who swears off the booze and finds himself standing face to face with the Divvil Himself. “The stuff of greatness,” say the posters. “Do not miss this play!” Yes, that’s what I wrote in The Wall Street Journal, except for the gratuitous exclamation point, and I meant every word (TT).

Archives for 2007

BOOK

David Parkinson, The Rough Guide to Film Musicals (Rough Guides, $14.99 paper). A decently written, unexpectedly sensible primer that walks you through the long and winding road that leads from The Jazz Singer to Chicago. Some films are undervalued, others overrated, but for the most part Parkinson plays it down the center, steering clear of the twin ditches of academic theory and camp silliness. If Sweeney Todd has you wondering whether there’s more to the genre than Busby Berkeley, this is a good place to find out what it’s all about (TT).

CD

Bill Evans, Conversations With Myself. Looking for the perfect Christmas present, either for yourself or someone you love? Try this classic 1963 album, on which the most influential jazz pianist of the postwar era overdubbed himself–twice. Listen to Evans Nos. 1, 2, and 3 playing Alex North’s “Love Theme from Spartacus” and see if the hair on the back of your neck doesn’t stand straight up. That was the first Bill Evans track I ever heard, and the impression it made on me back in high school has yet to fade (TT).

DVD

Get Carter. No, not the pointless Sylvester Stallone remake, but the original diamond-hard 1971 neo-noir masterpiece in which Michael Caine is out for revenge and doesn’t care who gets hurt along the way. After making this astonishing film, Mike Hodges dropped off the scope for three decades of mostly unmemorable slogging, only to resurface in 1999 with the similarly gripping Croupier. If you liked Croupier, what are you waiting for? (TT).

TT: Present and accounted for

Regular readers of this blog will recognize the name of Louis Kaufman, the great American violinist and art collector who made the first long-playing recording of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, played on the soundtracks of Gone With the Wind, The Adventures of Robin Hood, The Best Years of Our Lives, and Psycho, performed with Aaron Copland, Francis Poulenc, and Darius Milhaud, bought the first painting that Milton Avery ever sold, and wrote a delightful memoir called A Fiddler’s Tale: How Hollywood and Vivaldi Discovered Me. Alas, I never met Kaufman–he died in 1994 at the age of eighty-eight–but I’ve been corresponding with Annette, his wife and accompanist, for the past couple of years, and on Sunday I had the honor of showing her the Teachout Museum and taking her to lunch.

Regular readers of this blog will recognize the name of Louis Kaufman, the great American violinist and art collector who made the first long-playing recording of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, played on the soundtracks of Gone With the Wind, The Adventures of Robin Hood, The Best Years of Our Lives, and Psycho, performed with Aaron Copland, Francis Poulenc, and Darius Milhaud, bought the first painting that Milton Avery ever sold, and wrote a delightful memoir called A Fiddler’s Tale: How Hollywood and Vivaldi Discovered Me. Alas, I never met Kaufman–he died in 1994 at the age of eighty-eight–but I’ve been corresponding with Annette, his wife and accompanist, for the past couple of years, and on Sunday I had the honor of showing her the Teachout Museum and taking her to lunch.

Annette Kaufman is ninety-three years old, but you wouldn’t guess it to look at her–or talk to her. Not only is she still easily recognizable as the same woman who sat for Avery six decades ago, but she is a lively, bustling raconteuse who continues to consume art by the carload (she flew to New York from her Los Angeles home to see Prokofiev’s War and Peace at the Met). Judging by our conversation, she remembers everything she’s seen or heard with a clarity not even slightly diminished by age. I’d been careful to ask whether she could climb the stairs to my third-floor apartment, but it turned out that I was wasting my breath. Not only did she negotiate both flights of stairs with near-arrogant ease, but she took a cab straight from the Upper West Side bistro where we ate omelettes aux fines herbes to the Pissarro retrospective at the Jewish Museum. Spending three hours in her company made me feel…well, lazy.

Annette Kaufman is ninety-three years old, but you wouldn’t guess it to look at her–or talk to her. Not only is she still easily recognizable as the same woman who sat for Avery six decades ago, but she is a lively, bustling raconteuse who continues to consume art by the carload (she flew to New York from her Los Angeles home to see Prokofiev’s War and Peace at the Met). Judging by our conversation, she remembers everything she’s seen or heard with a clarity not even slightly diminished by age. I’d been careful to ask whether she could climb the stairs to my third-floor apartment, but it turned out that I was wasting my breath. Not only did she negotiate both flights of stairs with near-arrogant ease, but she took a cab straight from the Upper West Side bistro where we ate omelettes aux fines herbes to the Pissarro retrospective at the Jewish Museum. Spending three hours in her company made me feel…well, lazy.

In her youth Mrs. Kaufman was a wonderfully elegant and sensitive pianist, as you can hear for yourself on the bonus CD bound into A Fiddler’s Tale. Nowadays she’s too busy giving away the Louis and Annette Kaufman Collection to play much piano, but I have no doubt that if circumstances required her to do so, she could toss off the keyboard part to a Mozart violin sonata with the same casual grace that she brings to her reminiscences of the famous musicians, writers, and painters whom she and her husband knew. “A very interesting man,” she said when I showed her “Apples on a Table,” my 1923 Marsden Hartley lithograph. “Louis and I met him one day in Milton’s studio.” I did my best not to goggle.

I took it upon myself to suggest that Mrs. Kaufman pay a visit to the Martin Puryear show currently on display at the Museum of Modern Art, which felt a bit like offering advice to my grandmother on how to suck eggs. Be that as it may, she snapped up my recommendation with what I gather is her customary enthusiasm. “I just joined MoMA!” she replied. “That means I can take a friend with me!”

I also told her about The Letter, only to learn that she’s been going to Santa Fe Opera every August since shortly after I was born.

“That’s perfect timing,” I said. “The premiere is on August 1, 2009.”

“I’ll be there,” she replied.

I don’t doubt it.

TT: Almanac

Deck us all with Boston Charlie,

Walla Walla, Wash., an’ Kalamazoo!

Nora’s freezin’ on the trolley,

Swaller dollar cauliflower alley-garoo!

Don’t we know archaic barrel

Lullaby Lilla Boy, Louisville Lou?

Trolley Molly don’t love Harold,

Boola boola Pensacoola hullabaloo!

Walt Kelly, Deck Us All With Boston Charlie

TT: Men at work (IV)

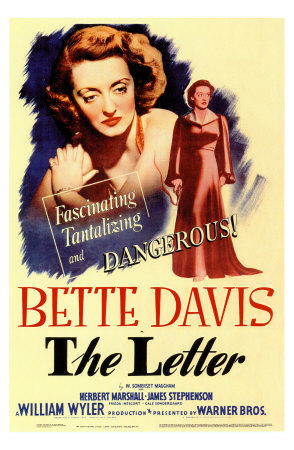

Don’t hold me to it, but The Letter may be the first opera in the history of classical music that’s ahead of schedule. I finished drafting my libretto in August, and Paul Moravec, my collaborator, has now written the music for five of the opera’s eight scenes. We have a director (Jonathan Kent) and a cast (no names yet, but you’ll be impressed). Richard Gaddes, who runs Santa Fe Opera, tells us that everybody in his shop is pleased with the completed scenes that Paul sent them a few weeks ago. Since our contract calls for us to deliver the piano score next June in anticipation of a premiere date of August 1, 2009, I’d say we’re cooking along fairly nicely. We’ve even gotten paid!

So what could possibly go wrong? Plenty. We like what we’ve written so far, but we won’t know how well it works until we start to see and hear it sung, and we expect to do a lot of tinkering between now and the summer of 2009. In addition, Paul and I have already spent a great deal of time thinking and talking about exactly what we’re trying to do, starting long before we actually began to write the opera and continuing to the present moment. Stephen Sondheim says that the first step in a successful collaboration is to make sure that everybody is writing the same show. We’re doing our best to follow his advice.

So what could possibly go wrong? Plenty. We like what we’ve written so far, but we won’t know how well it works until we start to see and hear it sung, and we expect to do a lot of tinkering between now and the summer of 2009. In addition, Paul and I have already spent a great deal of time thinking and talking about exactly what we’re trying to do, starting long before we actually began to write the opera and continuing to the present moment. Stephen Sondheim says that the first step in a successful collaboration is to make sure that everybody is writing the same show. We’re doing our best to follow his advice.

One of the things we both realized early on was that the show we wanted to write was going to be different in theatrical effect from the Somerset Maugham play on which The Letter is based. Maugham’s play, as I pointed out back in August, is both prosy and naturalistic. It’s also exceedingly cynical in its portrayal of the thwarted love of the principal characters. The problem is that prosy, cynical naturalism is not the stuff of which great opera libretti are made. “Consistency of character and reality of events are qualities which need not be accompanied by music,” Karl Kraus said. He got that right. To justify the extraordinary fact that the characters in an opera sing instead of speak, you have to give them something emotionally compelling enough to be worth singing about. Otherwise, you’ll end up with a show in which words and music are at war with one another. Try to imagine, say, a musical version of The Narrow Margin and you’ll see what I mean. Sure, the plot is exciting, and tough-guy lines like “She’s a sixty-cent special–cheap, flashy, strictly poison under the gravy” sound great when rasped out by Charles McGraw–but can you really hear them being sung by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau?

So in addition to making Maugham’s flat-textured dialogue lyrical enough to sing, which meant rewriting it virtually from scratch, I also had to heighten the emotional climate of The Letter in such a way as to give Paul, whose music is very intense and dramatic, sufficient room to maneuver. One of the ways I did this was by adding “operatic” situations to the plot. The biggest change I made was to insert a courtroom scene in which Leslie Crosbie (the Bette Davis character, if you’ve seen the movie) is confronted by the ghost of Geoff Hammond, the man she killed in Scene 1. Of course he’s really a hallucination, not a ghost, but the effect is the same, and Geoff’s unexpected reappearance in Scene 7 also gives the tenor (yep, he’s a tenor) a chance to sing a full-scale aria:

You told them that I raped you,

You spat upon my honor,

You bought back your letter,

You shamed my lover–

And for that you must die.

I hope they hang you, Leslie,

At the end of a long silk rope.

I’ll watch you dangle,

Then I’ll see you in hell!

Nothing remotely like this occurs in Maugham’s play, but it is, needless to say, a quintessentially operatic situation, and I was inspired to create it by a remark made by E.M. Forster in a lecture he gave in 1948 about one of my favorite operas, Benjamin Britten’s Peter Grimes: “It amuses me to think what an opera on Peter Grimes would have been like if I had written it. I should certainly have starred the murdered apprentices. I should have introduced their ghosts in the last scene, rising out of the estuary, on either side of the vengeful greybeard, blood and fire would have been thrown in the tenor’s face, hell would have opened, and on a mixture of Don Juan and the Freischütz I should have lowered my final curtain.”

Nothing remotely like this occurs in Maugham’s play, but it is, needless to say, a quintessentially operatic situation, and I was inspired to create it by a remark made by E.M. Forster in a lecture he gave in 1948 about one of my favorite operas, Benjamin Britten’s Peter Grimes: “It amuses me to think what an opera on Peter Grimes would have been like if I had written it. I should certainly have starred the murdered apprentices. I should have introduced their ghosts in the last scene, rising out of the estuary, on either side of the vengeful greybeard, blood and fire would have been thrown in the tenor’s face, hell would have opened, and on a mixture of Don Juan and the Freischütz I should have lowered my final curtain.”

That isn’t quite what happens in the hallucination scene of The Letter, but you get the idea.

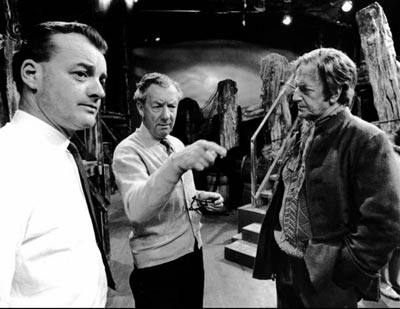

I don’t want you to think, by the way, that Paul and I sit around all day quoting Karl Kraus and E.M. Forster to one another. Our collaboration to date has been both aesthetically harmonious and a whole lot of fun, and though we’re both full-fledged eggheads, you wouldn’t always guess it from the way we work together. At our last session, for instance, Paul was telling me about the flashback in Scene 4 in which Leslie tells her lawyer what really happened on the night she shot Geoff. He was explaining how his music will cover the transition from Leslie’s jail cell in Singapore to the living room of her jungle bungalow.

I don’t want you to think, by the way, that Paul and I sit around all day quoting Karl Kraus and E.M. Forster to one another. Our collaboration to date has been both aesthetically harmonious and a whole lot of fun, and though we’re both full-fledged eggheads, you wouldn’t always guess it from the way we work together. At our last session, for instance, Paul was telling me about the flashback in Scene 4 in which Leslie tells her lawyer what really happened on the night she shot Geoff. He was explaining how his music will cover the transition from Leslie’s jail cell in Singapore to the living room of her jungle bungalow.

“Remember Wayne’s World?” Paul said. “I’ll just make the orchestra go whoosh-whoosh-whoosh, and we’ll be there.”

“Somehow I don’t think this is exactly the way that Otello got written,” I replied.

TT: Almanac

May all my enemies go to hell,

Noel, Noel, Noel, Noel.

Hilaire Belloc, “Lines For A Christmas Card”