Don’t hold me to it, but The Letter may be the first opera in the history of classical music that’s ahead of schedule. I finished drafting my libretto in August, and Paul Moravec, my collaborator, has now written the music for five of the opera’s eight scenes. We have a director (Jonathan Kent) and a cast (no names yet, but you’ll be impressed). Richard Gaddes, who runs Santa Fe Opera, tells us that everybody in his shop is pleased with the completed scenes that Paul sent them a few weeks ago. Since our contract calls for us to deliver the piano score next June in anticipation of a premiere date of August 1, 2009, I’d say we’re cooking along fairly nicely. We’ve even gotten paid!

So what could possibly go wrong? Plenty. We like what we’ve written so far, but we won’t know how well it works until we start to see and hear it sung, and we expect to do a lot of tinkering between now and the summer of 2009. In addition, Paul and I have already spent a great deal of time thinking and talking about exactly what we’re trying to do, starting long before we actually began to write the opera and continuing to the present moment. Stephen Sondheim says that the first step in a successful collaboration is to make sure that everybody is writing the same show. We’re doing our best to follow his advice.

So what could possibly go wrong? Plenty. We like what we’ve written so far, but we won’t know how well it works until we start to see and hear it sung, and we expect to do a lot of tinkering between now and the summer of 2009. In addition, Paul and I have already spent a great deal of time thinking and talking about exactly what we’re trying to do, starting long before we actually began to write the opera and continuing to the present moment. Stephen Sondheim says that the first step in a successful collaboration is to make sure that everybody is writing the same show. We’re doing our best to follow his advice.

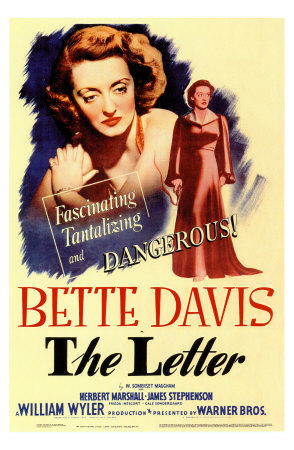

One of the things we both realized early on was that the show we wanted to write was going to be different in theatrical effect from the Somerset Maugham play on which The Letter is based. Maugham’s play, as I pointed out back in August, is both prosy and naturalistic. It’s also exceedingly cynical in its portrayal of the thwarted love of the principal characters. The problem is that prosy, cynical naturalism is not the stuff of which great opera libretti are made. “Consistency of character and reality of events are qualities which need not be accompanied by music,” Karl Kraus said. He got that right. To justify the extraordinary fact that the characters in an opera sing instead of speak, you have to give them something emotionally compelling enough to be worth singing about. Otherwise, you’ll end up with a show in which words and music are at war with one another. Try to imagine, say, a musical version of The Narrow Margin and you’ll see what I mean. Sure, the plot is exciting, and tough-guy lines like “She’s a sixty-cent special–cheap, flashy, strictly poison under the gravy” sound great when rasped out by Charles McGraw–but can you really hear them being sung by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau?

So in addition to making Maugham’s flat-textured dialogue lyrical enough to sing, which meant rewriting it virtually from scratch, I also had to heighten the emotional climate of The Letter in such a way as to give Paul, whose music is very intense and dramatic, sufficient room to maneuver. One of the ways I did this was by adding “operatic” situations to the plot. The biggest change I made was to insert a courtroom scene in which Leslie Crosbie (the Bette Davis character, if you’ve seen the movie) is confronted by the ghost of Geoff Hammond, the man she killed in Scene 1. Of course he’s really a hallucination, not a ghost, but the effect is the same, and Geoff’s unexpected reappearance in Scene 7 also gives the tenor (yep, he’s a tenor) a chance to sing a full-scale aria:

You told them that I raped you,

You spat upon my honor,

You bought back your letter,

You shamed my lover–

And for that you must die.

I hope they hang you, Leslie,

At the end of a long silk rope.

I’ll watch you dangle,

Then I’ll see you in hell!

Nothing remotely like this occurs in Maugham’s play, but it is, needless to say, a quintessentially operatic situation, and I was inspired to create it by a remark made by E.M. Forster in a lecture he gave in 1948 about one of my favorite operas, Benjamin Britten’s Peter Grimes: “It amuses me to think what an opera on Peter Grimes would have been like if I had written it. I should certainly have starred the murdered apprentices. I should have introduced their ghosts in the last scene, rising out of the estuary, on either side of the vengeful greybeard, blood and fire would have been thrown in the tenor’s face, hell would have opened, and on a mixture of Don Juan and the Freischütz I should have lowered my final curtain.”

Nothing remotely like this occurs in Maugham’s play, but it is, needless to say, a quintessentially operatic situation, and I was inspired to create it by a remark made by E.M. Forster in a lecture he gave in 1948 about one of my favorite operas, Benjamin Britten’s Peter Grimes: “It amuses me to think what an opera on Peter Grimes would have been like if I had written it. I should certainly have starred the murdered apprentices. I should have introduced their ghosts in the last scene, rising out of the estuary, on either side of the vengeful greybeard, blood and fire would have been thrown in the tenor’s face, hell would have opened, and on a mixture of Don Juan and the Freischütz I should have lowered my final curtain.”

That isn’t quite what happens in the hallucination scene of The Letter, but you get the idea.

I don’t want you to think, by the way, that Paul and I sit around all day quoting Karl Kraus and E.M. Forster to one another. Our collaboration to date has been both aesthetically harmonious and a whole lot of fun, and though we’re both full-fledged eggheads, you wouldn’t always guess it from the way we work together. At our last session, for instance, Paul was telling me about the flashback in Scene 4 in which Leslie tells her lawyer what really happened on the night she shot Geoff. He was explaining how his music will cover the transition from Leslie’s jail cell in Singapore to the living room of her jungle bungalow.

I don’t want you to think, by the way, that Paul and I sit around all day quoting Karl Kraus and E.M. Forster to one another. Our collaboration to date has been both aesthetically harmonious and a whole lot of fun, and though we’re both full-fledged eggheads, you wouldn’t always guess it from the way we work together. At our last session, for instance, Paul was telling me about the flashback in Scene 4 in which Leslie tells her lawyer what really happened on the night she shot Geoff. He was explaining how his music will cover the transition from Leslie’s jail cell in Singapore to the living room of her jungle bungalow.

“Remember Wayne’s World?” Paul said. “I’ll just make the orchestra go whoosh-whoosh-whoosh, and we’ll be there.”

“Somehow I don’t think this is exactly the way that Otello got written,” I replied.